THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

26)SOUTH AFRICA BRITISH INTELLIGENCE

4.3 South Africa, British naval intelligence, and the counterintelligence war

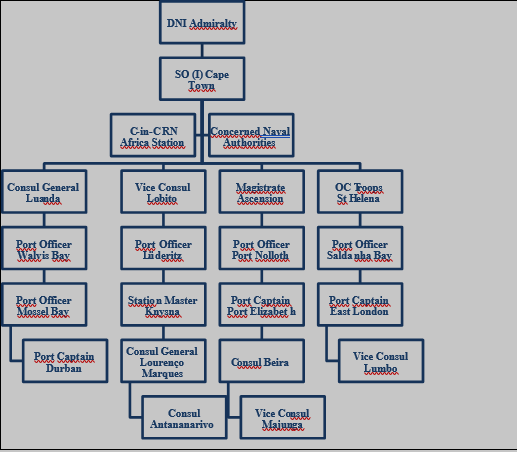

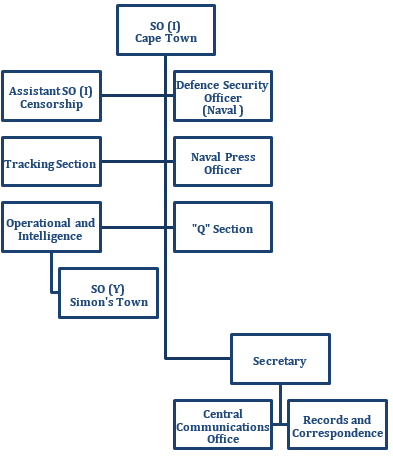

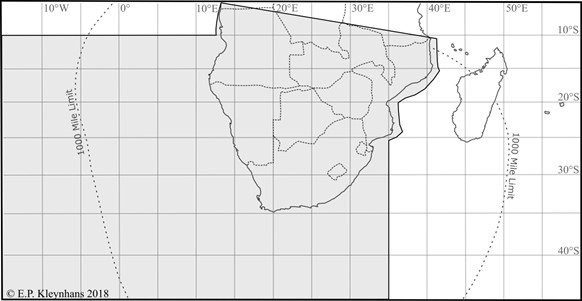

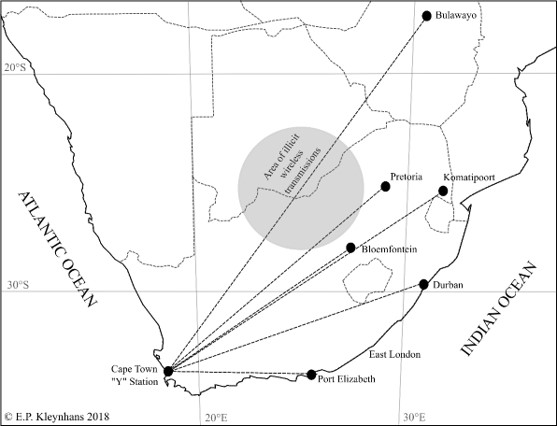

Before the outbreak of the war, the British Naval Intelligence organisation in South Africa consisted of a Staff Officer Intelligence (SO (I)), with a small staff, which operated from the Castle in Cape Town. In February 1939, Maj Charles Ransome RM assumed the position of SO (I) Cape Town. He became responsible for political intelligence, industrial intelligence, and port intelligence. These were acquired by keeping close contact with the UK High Commissioner and the British Trade Commissioner in South Africa, as well as the Intelligence Officers of the Royal Navy (RN) Africa Station based in Simon’s Town. Furthermore, the secretary of the SO (I) Cape Town kept a complete record of all naval and merchant shipping movements in South African waters. With the help of his staff, Ransome ensured the extraction of supplemental naval information from the South African press, the Lloyd’s Shipping Index, local shipping agents, and from the monthly reports submitted by the Reporting Officers within the Cape Intelligence Area (see Map 4.1 and Fig 4.6).

By 1938, and owing to the impending global war, the CNIC started plotting the movement of all German, Japanese and Italian merchant vessels in the Southern Oceans, as well as all potential armed merchant cruisers and commerce raiders. The SO (I) Cape Town subsequently reported the movement of each foreign warship to the Admiralty, and when such a vessel left the region, it was reported to the SO (I) into whose area it moved. The SO (I) Cape Town collected all of these reports and then drafted a daily intelligence summary which was forwarded to the Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) Africa Station for transmission to RN vessels within its area of command. At the time of the Munich Crisis, the C-in-C Africa Station identified six retired RN Officers for service on the staff of the SO(I) Cape Town. After an initial call-up in 1938, Ransome’s staff had been placed on a complete war footing by 30 August 1939. It comprised of additional sections, principally concerned with Tracking, Operational Intelligence, Security, Naval Press Relations and Censorship. To gain a complete understanding of the functioning of the CNIC during the war, each of the above sections will be discussed separately.

Fig 4.6: Pre-war organisation of the Cape Intelligence Area Reporting Officers

Map 4.1: The Cape Intelligence Area, 1939-1942

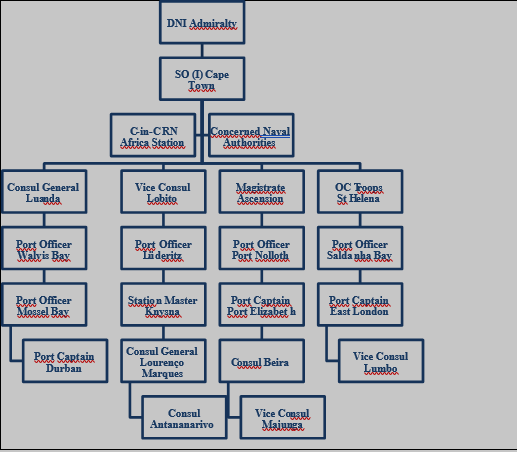

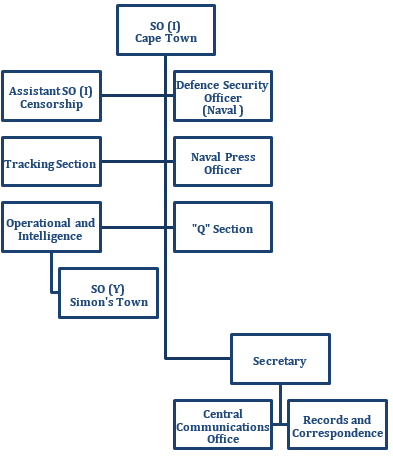

4.3.1 The Tracking Section

The establishment of a separate Tracking Section in September 1939 allowed for the centralised control over all shipping movements. The Tracking Section maintained a Merchant Shipping Plot, which included up to date data on the last known positions of all merchant vessels in the Cape Intelligence Area. Moreover, the introduction of the VESCA system allowed for the regular updating of the Merchant Shipping Plot. Ransome received all ‘IN’ VESCA messages from the designated Reporting Officers within the Cape Intelligence Area, in addition to those from adjacent areas where shipping was known to head for South African waters. The Admiralty, as well as the authorities at the various ports of destination, received all ‘OUT’ VESCA messages from Ransome in Cape Town. Ransome was also responsible for transmitting all VESCAs from Lourenço Marques and Beira onwards due to the high cable charges in Portuguese East Africa. Because of the sudden increase in its organisation and operational responsibilities (see Fig 4.7), the CNIC relocated to a new building in Dock Road, near the main entrance to the Cape Town harbour. The new property, known as Seaward House, was also the headquarters of the Seaward Defence Force (SDF). Between November 1939 and October 1940, there were several increases in the staff of the CNIC due to the continuous increment of cypher work.

Fig 4.7: Organisation of the Cape Naval Intelligence Centre, 1940-1942

Towards the end of 1940, Ransome established a Central Communications Office under his direct control at the CNIC. The Central Communications Office assumed responsibility for the receipt, dispatch and distribution of all signals. These signals were addressed to the SO (I) Cape Town, Naval Liaison Officer, Naval Control Service Officer, the Sea Transport Officer at Cape Town, as well as the Director of the SDF and the RN Authorities in Cape Town and Simon’s Town respectively. Additionally, Ransome’s Cypher Staff handled all Admiralty general messages, East Indies Station messages, “Q” messages , VESCA signals, routeing instructions, disposition signals, enemy reports, all high-grade cyphers and all other coded messages. The Central Communications Office was also responsible for relaying these messages to all other concerned parties within the sphere of the CNIC. As he was based in Cape Town, Ransome personally controlled all VESCA messages originating from Cape Town, and by 1940 introduced a message system known as VELOX. This messaging system allowed for confidential shipping information to pass between ports and Reporting Officers in the Cape Intelligence Area (see Fig 4.9). The VELOX telegrams were essentially a coded and re-coded message. It was comprised of the VELOX in plain language; the ship’s signal letter along with a dummy letter; the estimated time of arrival, and the time of origin and date in plain language.

Towards the end of 1940, Ransome established a Central Communications Office under his direct control at the CNIC. The Central Communications Office assumed responsibility for the receipt, dispatch and distribution of all signals. These signals were addressed to the SO (I) Cape Town, Naval Liaison Officer, Naval Control Service Officer, the Sea Transport Officer at Cape Town, as well as the Director of the SDF and the RN Authorities in Cape Town and Simon’s Town respectively. Additionally, Ransome’s Cypher Staff handled all Admiralty general messages, East Indies Station messages, “Q” messages , VESCA signals, routeing instructions, disposition signals, enemy reports, all high-grade cyphers and all other coded messages. The Central Communications Office was also responsible for relaying these messages to all other concerned parties within the sphere of the CNIC. As he was based in Cape Town, Ransome personally controlled all VESCA messages originating from Cape Town, and by 1940 introduced a message system known as VELOX. This messaging system allowed for confidential shipping information to pass between ports and Reporting Officers in the Cape Intelligence Area (see Fig 4.9). The VELOX telegrams were essentially a coded and re-coded message. It was comprised of the VELOX in plain language; the ship’s signal letter along with a dummy letter; the estimated time of arrival, and the time of origin and date in plain language.

The Central Communications Office, furthermore, oversaw the distribution of shipping information to all Allied vessels in South African harbours as well as those at sea. All Allied merchant shipping within South African harbours received a briefing on relevant shipping information just before their departure. As a result, the Merchant Shipping Plot in each vessel was a direct replica of that kept in Ransome’s office. Ransome supplied this information in the form of Cape Area Intelligence Notes and other Intelligence Summaries. These incorporated detailed information on all merchant ships in South African harbours including Lourenço Marques and Beira and all ships travelling between South African ports. Further details encompassed vessels due to arrive at South African ports from adjoining intelligence areas; lists of ships sailing from South African ports after each Allied vessel departed, and ships approaching the Cape Intelligence Area from adjacent areas that the Allied vessels may encounter.

A further system of Daily Encounter signals sent from Simon’s Town ensured that all Allied vessels at sea could maintain accurate and up to date shipping plots. These messages, derived according to a system of squares, proved unsatisfactory, and by 1941 a new method of passing information to Allied vessels at sea had come into effect. This system embodied a series of signals for shipping travelling from South African ports, known as AS and ES messages for the South Atlantic Station, FS messages for the Freetown area, and MS messages for the East Indies. The AS signals reported on all northbound shipping in the Atlantic Ocean, while the ES signals reported on all eastbound shipping in the Indian Ocean. The AS and ES signals remained in use until August 1942. After this, the SO Mercantile Movements at Combined Headquarters assumed the responsibility for tracking duties as well as reporting all known shipping movements to Allied vessels for the remainder of the war.

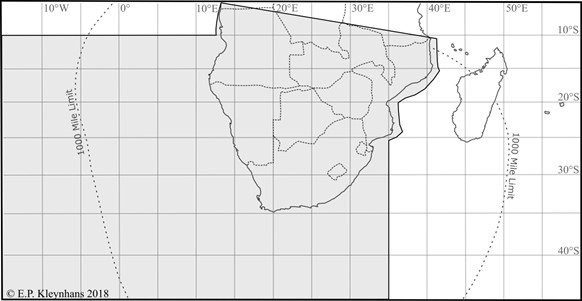

In March 1942, the headquarters of the C-in-C South Atlantic were relocated to Simon’s Town. This transfer severely altered the operational boundaries of the Cape

In March 1942, the headquarters of the C-in-C South Atlantic were relocated to Simon’s Town. This transfer severely altered the operational boundaries of the Cape

Intelligence Area (see Map 4.2). The Eastern Boundary hence extended from the South Pole up to 35°E meridian to the coast of Africa, and from these along the coast to the northern border of Portuguese East Africa. The Western Boundary extended from the South Pole up to the meridians of 26°W and 40°S, and from there along the parallel 10°S to the coast of Africa near the mouth of the Congo River. Though the land boundary in the north remained undefined, Angola and Portuguese East Africa were considered to form the natural northern boundary.

A Combined Headquarters was established in Cape Town during the month of August 1942 in the Old University buildings in Cape Town. The CNIC also moved from Seaward House to the Combined Headquarters. The Tracking Section was subsequently removed from Ransome. He was thus no longer responsible for collating information regarding the movement of shipping. The Mercantile Movements Section at Combined Headquarters, under the control of an SO from the South Atlantic Station, assumed responsibility for this task. This led to a marked reduction in the staff of the CNIC in 1942 and 1943.

Map 4.2: The Cape Intelligence Area, 1942-1945

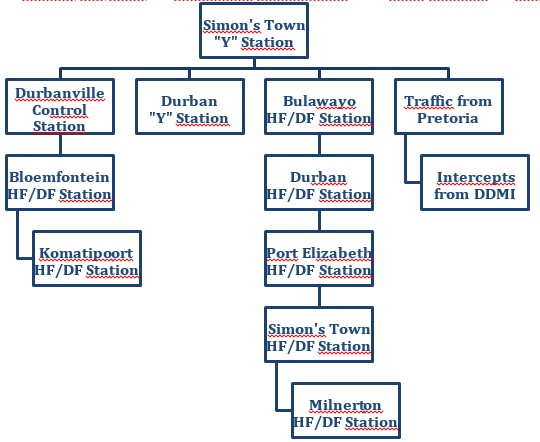

The arrival of Lt Cdr J.S. Bennet in Simon’s Town in March 1940 marked the beginning of the RN “Y” Organisation in South Africa during the war. The “Y” Organisations in general formed the foundation of all British wartime Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) work. Their explicit focus was on the interception and deciphering of Axis wireless communications. Bennet was appointed as the SO (Y) on the staff of the C-in-C South Atlantic. He and his staff immediately established a continuous watch over each wireless transmission passing through the “Y” Station in Simon’s Town. They also copied all similar traffic originating from the known South African “Y” Station located at Robert’s Heights in Pretoria. The “Y” Station in Pretoria fell under the direct control of Major J. Kreft, the then Deputy Director of Military Intelligence in South Africa. After reaching an agreement with the South African Post Office (SAPO), Bennet agreed to the creation of a High-Frequency/Direction Finding (HF/DF) station near Milnerton in Cape Town. This station became effective on 19 April, and fell under the control of the SAPO. Thereafter a second HF/DF station, along with a “Y” Station, was established in Durban at the end of April. By June 1941, a third HF/DF station had come into operation at Bulawayo in Southern Rhodesia. Shortly hereafter Brig H.J. Lenton, the Union Postmaster-General, approved the transfer of the Milnerton HF/DF Station to Bennet and his “Y” Organisation.

Saboteurs regularly interfered with communications between these stations by simply cutting the trunk lines which connected them to one another. The result was that on several occasions all of the HF/DF Stations in the Union were completely isolated from one another for lengthy periods of time. These interruptions adversely affected all interception work. After wireless sets were installed at the HF/DF stations at Simon’s Town, Durban and Bulawayo, the situation improved somewhat. In the event of further sabotage, a simple slide-rule code, established by Bennet, allowed these stations to communicate intercepted bearings and instructions rapidly to Simon’s Town.

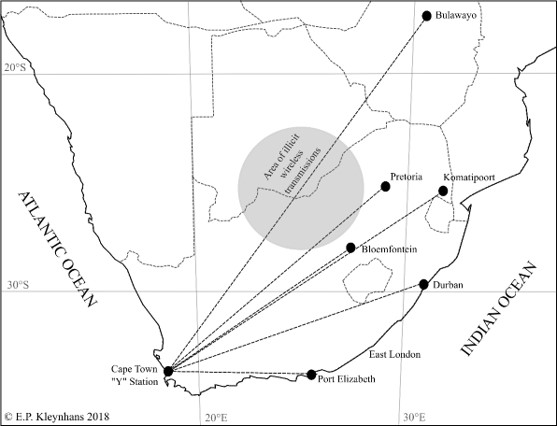

Following the commencement of the Japanese submarine operations in the Mozambique Channel in June 1942, the “Y” Organisation in South Africa was able to help intercept wireless transmissions from IJN vessels. This occurred despite the fact that none of the operators in the Union were being trained in reading Japanese naval codes. After the “Y” operators studied the code, they were able to identify and cover all Japanese transmissions and pass it on to the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park for further deciphering. The signals intercepted by the HF/DF stations in the Union (see Map 4.3), could then be used to pinpoint the exact location of the Japanese wireless transmissions. As a result, a constant track of the IJN vessels operational in the Mozambique Channel during 1942 could be maintained. The operators were able to achieve this without relinquishing their normal watch on the German naval frequencies during this period.

In May, the Admiralty made a further request. The “Y” Organisations under the overall control of the South African Director of Military Intelligence, Col Ernst Malherbe, should copy all wireless traffic between Lisbon and Lourenço Marques. The same should be done with Vichy French traffic from Madagascar. The information would then be forwarded to the Admiralty at Whitehall. This process was achieved through forwarding a copy of the intercepted messages and bearings to Bennet in Simon’s Town from Pretoria by surface mail, as no high-speed receiving gear was available there.

Following the instalment of a recording apparatus at the Simon’s Town “Y” Station, the situation somewhat improved. Poor reception and limited staff, however, affected the amount of traffic handled. The arrival of an assistant SO (Y) by the end of 1941, along with a number of trained RN telegraphists, allowed Bennet to cover his increasing commitments to a larger degree. By June, a further HF/DF station – built and manned by the SAPO – had become operational in Port Elizabeth.

By the end of April 1942, Lenton had appealed to the C-in-C South Atlantic to allow Bennet to inspect his “Y” Organisation, and draw up a report with suggestions for improvements in its operations. The Postmaster-General’s “Y” Organisation comprised of a control station at Sunningdale near Johannesburg, and two HF/DF stations located at Bloemfontein and Komatipoort. A number of mobile direction finding units also supplemented the work of these stations. The principal aim of Lenton’s “Y” Organisation was to intercept all illegal transmissions within the Union, and to assist in general internal security work. During Bennet’s inspection, he established that these stations had little to no operational success. This was mainly due to a lack of organised search and coordination efforts, as knowledge regarding the highly specialised nature of work was also wanting. Lenton therefore suggested that his “Y” Organisation revert to being under the control of Bennet in Simon’s Town.

An immediate advantage of this new arrangement was that all HF/DF stations in the Union were now concerned with naval interception duties. At the same time, the former SAPO stations could focus purely on commercial interception work when necessitated by the Admiralty. Moreover, the staff of the SO (Y) Organisation could now concentrate exclusively on naval “Y” work. The reorganisation took place as follows:

An immediate advantage of this new arrangement was that all HF/DF stations in the Union were now concerned with naval interception duties. At the same time, the former SAPO stations could focus purely on commercial interception work when necessitated by the Admiralty. Moreover, the staff of the SO (Y) Organisation could now concentrate exclusively on naval “Y” work. The reorganisation took place as follows:

• The control station at Sunningdale closed down, and all equipment and operators moved to Durbanville, near Cape Town, where a new control station was established. This relocation allowed for more effective management of the control station by the SO (Y) and his staff.

• The HF/DF station at Bloemfontein was subsequently connected to the SO “Y” Organisation in Simon’s Town by a trunk line. This allowed for centralised control over its functioning.

• A system of indexing cards, documenting all unknown call-signs and other useful information, was instituted at the Central Post Office in Cape Town. All logs and other matter were forwarded to the SO (Y).

It is of particular interest to note that the Admiralty maintained complete control over the “Y” Organisation in South Africa throughout the war, mainly due to security reasons and distrust of certain elements within the UDF. From the outbreak of the war, Bennet and his staff proved wary of Malherbe’s “Y” Organisation. The principal reason for their suspicion was the fact that the messages that passed through his station at Roberts Heights, were prone to compromise owing to the existence of known subversive elements within the UDF. Moreover, the existence of two largely similar “Y” Organisations within South Africa, one controlled by the Deputy Director of Military Intelligence in Pretoria and the other by the SO (Y) in Simon’s Town, proved unacceptable, especially from an operational approach. The Admiralty was especially opposed to this state of affairs, particularly due to the duplication of work and constant concerns over security. Consequently, these two organisations never merged during the war, largely due to the continued operational distrust shown by the Admiralty towards the UDF.

By August 1942, the “Y” Organisation had undergone further restructuring due to the opening of the Combined Headquarters in Cape Town (see Fig 4.8). The SO (Y) and his staff relocated to the Combined Headquarters. Lenton authorised the instalment of a number of private wires that connected the Cable and Wireless Office, the Durbanville Control Station, the Central Communications Office, the various Operations Rooms at Combined Headquarters, and the private residence of the SO (Y) with one another. In this way, greater cooperation was ensured. Moreover, the “Y” Station at Simon’s Town served as the control station for the entire “Y” Organisation in South Africa, with all trunk lines from the HF/DF stations from across the Union terminating there. This office was also equipped with receivers and a wireless transmitter for uninterrupted communication should the trunk lines fail. The office operated around the clock, with all plotting and other “Y” intelligence disseminated from there onwards for operational purposes.

Fig 4.8: The SO “Y” Organisation in South Africa during the war

During the latter half of 1942, there was a notable growth in the importance of the SO “Y” Organisation in the Union. Its increased significance was a direct consequence of the intensified German U-boat campaign in South African waters. The various HF/DF stations successfully plotted the locations and movements of the German U-boats while they were operating off the South African coast. Following an official visit from Capt H.R. Sandwith RN to the Union in November, and upon his recommendation, the Admiralty expressed their intention of installing new measuring equipment and building of an entirely new HF/DF Station at Durbanville.

Map 4.3: The local “Y” Organisation and principal HF/DF stations in southern Africa, along with the general centre of illegal transmissions in the Union

The new HF/DF Station at Durbanville opened in March 1943. It proved immensely successful in connection with receiving and intercepting wireless communication, and ensuring improved coordination. The Durbanville “Y” Station especially maintained a continuous watch over all German, Italian, Japanese, French and Portuguese naval frequencies of vessels operational in Southern Oceans. It directed the control station at Durbanville to the frequencies on which such transmissions were heard. This station also recorded all high-speed commercial traffic from Lisbon to Lourenço Marques, as well as traffic intercepted from Rome. Intercepted traffic of this nature was then cabled to the Director of Naval Intelligence (DNI) at Whitehall and the GC&CS at Bletchley Park for information and operational purposes. The station also maintained constant monitoring over Union transmissions for internal security reasons.

During this period, an enhanced alarm flash circuit was installed at all HF/DF stations, which allowed the control station at Cape Town to communicate with its six substations within ten to fifteen seconds after the fixing of an illicit wireless transmission. As a result, Bennet and his staff were able to obtain accurate bearings of all Axis naval vessels operating along the South African coast, which greatly assisted in the anti-submarine warfare (ASW) measures and operations in these waters.

During this period, an enhanced alarm flash circuit was installed at all HF/DF stations, which allowed the control station at Cape Town to communicate with its six substations within ten to fifteen seconds after the fixing of an illicit wireless transmission. As a result, Bennet and his staff were able to obtain accurate bearings of all Axis naval vessels operating along the South African coast, which greatly assisted in the anti-submarine warfare (ASW) measures and operations in these waters.

In August 1943, Bennet’s “Y” Organisation proved instrumental in obtaining a rudimentary plot of the wireless set operated by Sittig. By intersecting the bearings taken by several HF/DF stations in the Union, the plot indicated that Sittig transmitted from a position close to the border with the then Bechuanaland. In order to gain an accurate plot of the Sittig wireless set, a number of mobile DF units searched the area for nine days without locating the transmitter. Their inability to do so was largely due to several technical difficulties encountered with the harsh terrain. The fact that the Vryburg area was known to be a hotbed of OB support was equally problematic.

During this period, Bennet’s “Y” Organisation also picked up on the proposed rendezvous between Sittig and a U-Boat near Cape St Francis. By November, Smuts had given his blessing for a renewed drive to make a concerted move against the FELIX transmitter. Lenton and Maj Michael Ryde, the deputy MI5/MI6 representative in the Union, planned the operation in December. Nonetheless, it was temporarily put on hold in January 1944 for a number of political reasons. In February, a renewed operation against the FELIX transmitter was planned between Lenton, Ryde and Bennet, though this plan also never came to fruition. Its failure was partly due to growing British interagency rivalries as well as continued concerns over the political loyalties of various Union officials. Instead, Bennet issued a raid of his own near Vryburg, without the consent of Ryde. The raid proved a dismal failure as the FELIX wireless set was not located. The planned swoop was also outside of Bennet’s normal operational domain. During the rest of the war, no concerted move was made against the FELIX Organisation in South Africa, and Sittig managed to successfully evade the security authorities well after the cessation of hostilities in 1945.

During this period, Bennet’s “Y” Organisation also picked up on the proposed rendezvous between Sittig and a U-Boat near Cape St Francis. By November, Smuts had given his blessing for a renewed drive to make a concerted move against the FELIX transmitter. Lenton and Maj Michael Ryde, the deputy MI5/MI6 representative in the Union, planned the operation in December. Nonetheless, it was temporarily put on hold in January 1944 for a number of political reasons. In February, a renewed operation against the FELIX transmitter was planned between Lenton, Ryde and Bennet, though this plan also never came to fruition. Its failure was partly due to growing British interagency rivalries as well as continued concerns over the political loyalties of various Union officials. Instead, Bennet issued a raid of his own near Vryburg, without the consent of Ryde. The raid proved a dismal failure as the FELIX wireless set was not located. The planned swoop was also outside of Bennet’s normal operational domain. During the rest of the war, no concerted move was made against the FELIX Organisation in South Africa, and Sittig managed to successfully evade the security authorities well after the cessation of hostilities in 1945.