THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

29)THE NAVAL PRESS REL. SECTION

.3.4 The Naval Press Relations Section

Before the war, the officer on the staff of the SO (I) Cape Town responsible for Press Censorship, Press Relations, and Naval Publicity, was closely connected with publicity matters. This person therefore had a knack for dealing with the South African press. The Naval Press Officer (NPO) had two responsibilities. Firstly, he had to censor all naval material and information made available to the media. Secondly, he had to arrange facilities for the media to procure naval information made available for publication. This was, however, only possible through the development of good personal relations with the editors and members of the South African Press Corps, broadcast personnel, film production managers, authors, and all relevant Union Government Departments. Moreover, the Naval Press Office of the CNIC had to carry out all of the duties normally performed by the Naval Information Division of the Admiralty. In addition, the NPO was responsible for the duties of the Naval Advisory Staff of the Ministry of Information in the UK.

From April 1940, Port NPOs assumed similar duties at Durban, East London and Port Elizabeth, and were responsible for all local press and related liaison duties. By March 1942, the appointment of an Assistant NPO at Cape Town greatly improved the day-to-day operation of the Naval Press Office. The Assistant NPO was a former editor at a prominent South African newspaper. The post was, however, abolished by November 1943, only to be reinstated in April 1945. It is worthy to note that the Naval Press Office and its sub-offices in South Africa, along with all matters connected with naval publicity, developed without any direct assistance from the Admiralty. Only after the NPO had visited London in December 1944 for training purposes, did the Admiralty regularly supply the Naval Press Office with suitable material. An assortment of books, articles and photos were hence distributed among Allied sailors.[1]

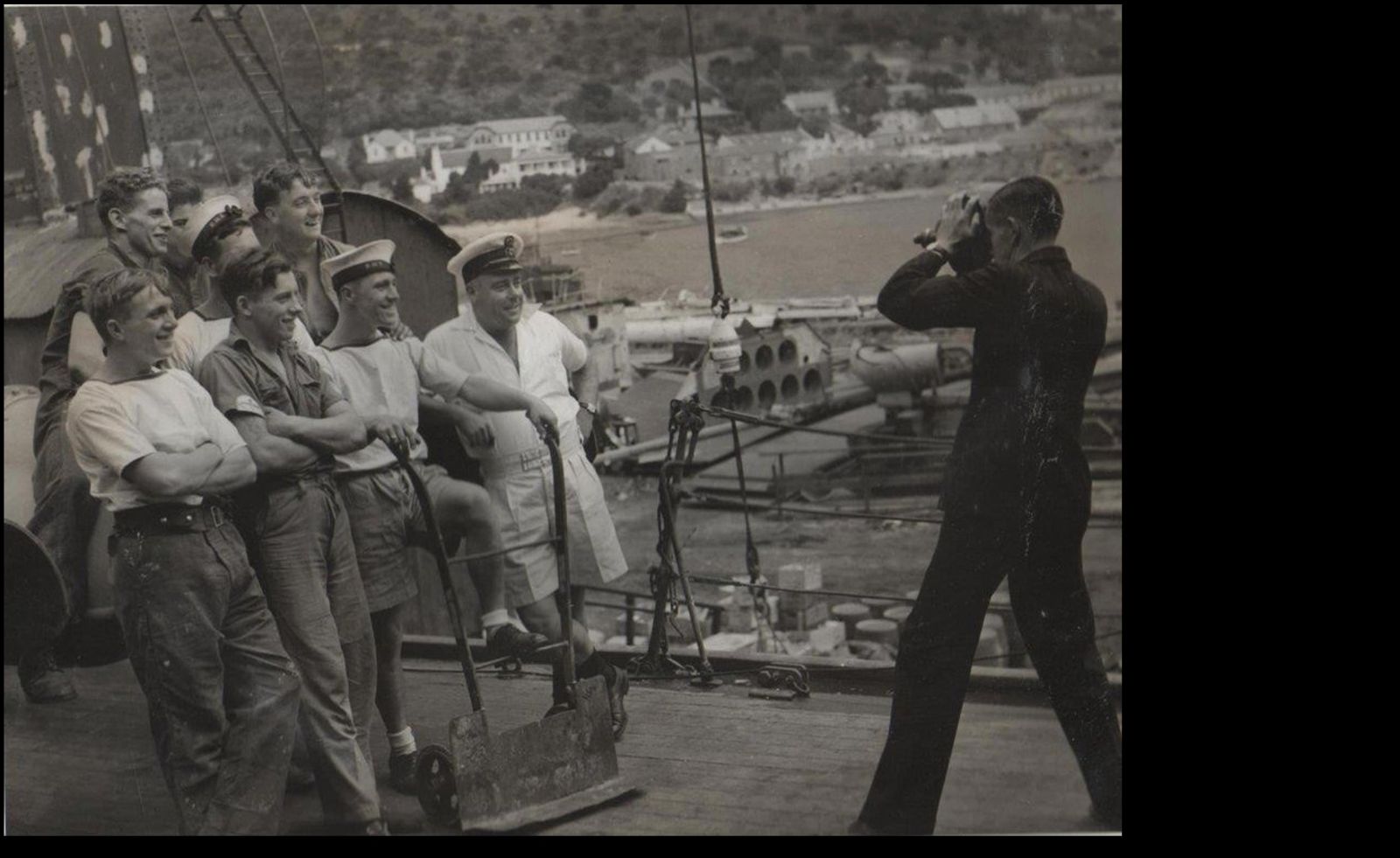

The NPO also had the responsibility of arranging Press visits to Allied naval vessels that called at South African ports, and in some cases, arranged special trips to sea for the South African reporters. This organisation showed no discrimination in this regard, and despite different political outlooks, even extended invites to reporters from Afrikaans newspapers which were conspicuously opposed to both the Smuts Government and the war. A number of carefully censored articles thus appeared in English and Afrikaans newspapers, primarily due to a good working relationship established by the NPO with both the RN and the SANF.

Fig 4.11: A journalist aboard a visiting Allied naval vessel during the war[2]

The photography of dock areas was similarly controlled by the NPO. The Naval Press Office applied certain statutory powers contained under Local Emergency War regulations to enforce compliance. Photography in dock areas, for instance, was only authorised when an officer of the Naval Press Office escorted the photographer. Needless to say, this responsibility placed an immense strain on the office of the NPO. The NPO also carried out all Press relation and censorship duties for the SANF upon a direct request from the Director of the SANF. The NPO furthermore had to maintain close liaison with the Navy League of South Africa, the Navy War Fund Committees as well as other maritime inclined bodies in the Union. The Naval Press Office further helped to organise the naval section of the Victory Cavalcade staged in Cape Town in April 1944, as well as the Navy Week held during the same year. Both the former and the latter exhibited the work of the RN, Fleet Air Arm and the SANF to the South African public.[3]

The basis of press control during the war, especially with regard to publishing the movements of shipping, was the statutory prohibition contained under Section 91(1) of the Defence Act of 1912. It read “… no information with respect to the movements or dispositions of the Union Defence Forces or other of His Majesty’s Forces, or of His Majesty’s ships shall be published in any newspaper, magazine, book, pamphlets or by any other means…”[4] Despite this legislation, there was no effective machinery to deal with or control the publication of information dealing with merchant shipping. The signing of the Voluntary Censorship Agreement took place in June 1940. This occurred as a result of negotiations carried out with the press by the South African Bureau of Information. The Agreement formalised control over the press and prohibited the publication of any news of a maritime nature without prior reference to the NPO.[5] In return, news of a maritime nature was provided to the press by the NPO whenever possible. Despite the Voluntary Censorship Agreement being nothing more than a gentleman’s agreement, all parties, including the anti-war newspapers, honoured the agreement throughout the war. The Union Government thus never enforced compulsory naval censorship during the war. This was largely the result of the good personal relationship between the various newspaper editors and the Naval Press Office.[6]

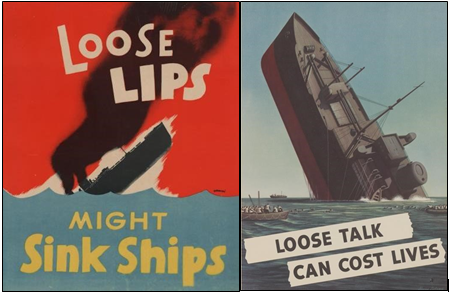

Fig 4.12: Allied wartime propaganda posters aimed at preventing careless talk about shipping[7]

As a result of the increased losses of merchant ships in South African waters, the Naval Press Office initiated a ‘Don’t Talk Campaign’ in 1942. The campaign was carried out in an endeavour to prevent careless talk about naval and shipping matters (see Fig 4.12). The danger that careless talk held for the safety of Allied shipping was accentuated by anti-British elements active in South Africa, as well as the Trompke Network known to operate out of Lourenço Marques.[8] The NPO started the ‘Don’t Talk Campaign’ in all earnest in February, with the explicit object of stopping loose talk on shipping matters. The campaign ran throughout the Union, and became commonly known as the ‘Don’t Talk about Ships or Shipping’ campaign. The NPO employed a variety of means to convey its message, including posters, notices in trains and buses, articles and advertisements in the press, radio broadcasts and films, to name a few. The South African Bureau of Information provided the necessary funding, and a large segment of the South African public supported the campaign during the war.[9]

[1] TNA, ADM 1/31006. History and Organisation of the Naval Intelligence Centre Cape Town. Naval Press Relations.

[2] South African National Museum of Military History, Masondo Reference Library. SA Navy Photo Collection, S.A. 1231.

[3] TNA, ADM 1/31006. History and Organisation of the Naval Intelligence Centre Cape Town. Naval Press Relations.

[4] South African Defence Act (13 of 1912).

[5] Monama, Wartime Propaganda in the Union of South Africa, pp. 70, 92.

[6] TNA, ADM 1/31006. History and Organisation of the Naval Intelligence Centre Cape Town. Naval Press Relations.

[7] http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O122410/loose-talk-can-cost-lives-poster-dohanos-stevan/; http://time.com/4591841/loose-lips-sink-ships-posters/ (Accessed on 8 June 2018).

[8] Monama, Wartime Propaganda in the Union of South Africa, p. 92.

[9] TNA, ADM 1/31006. History and Organisation of the Naval Intelligence Centre Cape Town. Naval Press Relations.