U.S. NAVY VP SQUADRONS IN BRAZIL - THE TIMES OF RICHARD ARNOLD AT VP 94

8)END OF JOURNEY IN BRAZIL

Each officer had collateral duties in the squadron in addition to flying. We used that knowledge to assist the Brazilians in setting up a squadron similar to ours. I had been an assistant communications officer as my collateral duty. My job was to help handle all incoming and outgoing messages to and from the squadron, most of which were in code.

We had aircraft code books which we took on every flight and an electric code machine (ECM) at our headquarters. The ECM was a machine like a typewriter which had two sets of five wheels inside. The wheels had the letters of the alphabet around the outside. Each day there was a different combination of letters set up on the wheels with a code name for the day. That way no two days code was the same. In addition, it was my job in the event we were compromised in any way, to set the two wheels up to read BOBBY JONES, send a message as to what happened and destroy the machine. Naturally, I thought I was a pretty important guy. (You all realize if you tell this to anybody, I’ll have to kill you.)

Needless to say, I couldn’t give all this to the Brazilians but the set up of the department was similar to ours. Each of us did that with our own departments. Before we set up the squadron, we had to teach them how to fly the airplanes. That was easier said than done because most of their pilots didn’t speak English and we didn’t speak Portuguese. There was usually one pilot or crew member who could interpret for us so it worked out okay. Some of the older pilots were pretty good but the younger ones couldn’t even hit the runway. I frequently just let them land in the grass alongside the runway. I figured they should be able to see that they were doing something wrong if they saw the runway next to them after they got on the ground.

Night flying was even more exciting. When we flew out over the ocean heading away from land, there was no horizon for them to orient themselves on. They had to fly by their instruments and they were all over the sky. When they turned toward land and could see city lights, they were alright. One night when we were out over the ocean, we broke a fuel line inside the airplane. The break was up in the tower under the wing where the mech sits. The gasoline all ran down into the bilge and we had several inches of fuel in the bottom of the airplane. The plane was filled with fumes which is the most dangerous thing. I was the only American on the plane and had to immediately convey to everybody there not to touch any switches or anything else that might create a spark.

Activating a microphone will produce a spark. We opened the cockpit windows and the blisters and got a flow of air going through the plane and headed for the field. Fortunately we weren’t too far out to sea so it didn’t take too long to get in. I couldn’t call the tower so I just went on in. The runway was clear and we got down okay. My feet were shaking on the rudder pedals. I could see Bob Malecki all the way in. We had a lot of fun down there and became friendly with some of the Brazilian pilots. One of them was named Orleans and was descended from royalty. Brazil apparently had a king at some time in the past and it was his family. He was a good pilot, loved to play cards and liked most of us. He and another pilot named Almeida became good friends of ours. Ray and Brad and I roomed together and Almeida hung a sign over our door saying Cave of the Aces.

During the training portion of our time down there we were stationed at Santa Cruz which was about forty miles out of Rio. Rotating crews, we got to know Capacabana Beach pretty well. Later when we set up the squadron the whole operation moved in to a field right in Rio harbor. There were no barracks there so we were given per diem and allowed to live on the beach. Dick Rowland moved in with us there. We didn’t have to fly much any more so we enjoyed ourselves - got very little sleep. Dick, Brad and I went up into the mountains to a big resort area. Unfortunately, it was out of season and there was nobody there.

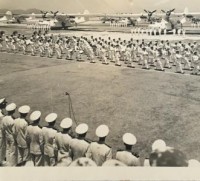

Late in our assignment there, Orleans had a reception and dinner for us. We had a formal presentation of our aircraft to the Brazilian Air Force and turned over eighteen PBYs to them. In return, they had a ceremony in which we were made honorary members of the Brazilian Air Force and they pinned Brazilian wings on us. It was a great ending to the Battle of the Atlantic as far as we were concerned. Shortly thereafter, we packed up our gear and headed back to the States for reassignment. We had no airplanes so we had to go back in PBMs. We took a DC-3 up to Bahia, then piled into a PBM for the rest of the trip home. We had spent some time searching for PBMs so we weren’t crazy about the idea. We all sacked out on the corrugated floor and tried to sleep away the trip, but a lot of heads came up everytime an engine popped. It took us five days to get back to Norfolk and my tour in VP-94 was over.

Richard Arnold returned to the US early in 1945

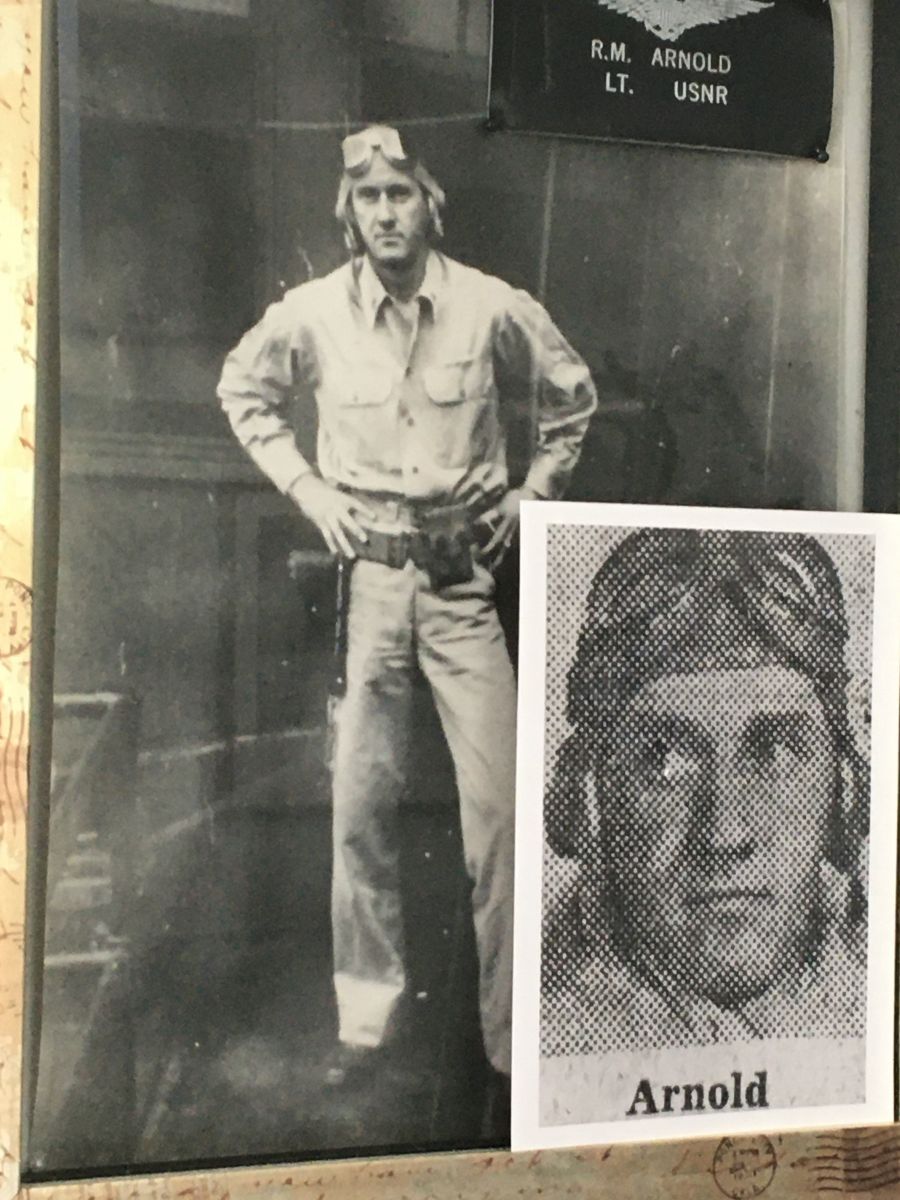

Lt Richard Arnold

Lt Arnold (far right) receiving Brazilian Air Force decoration.

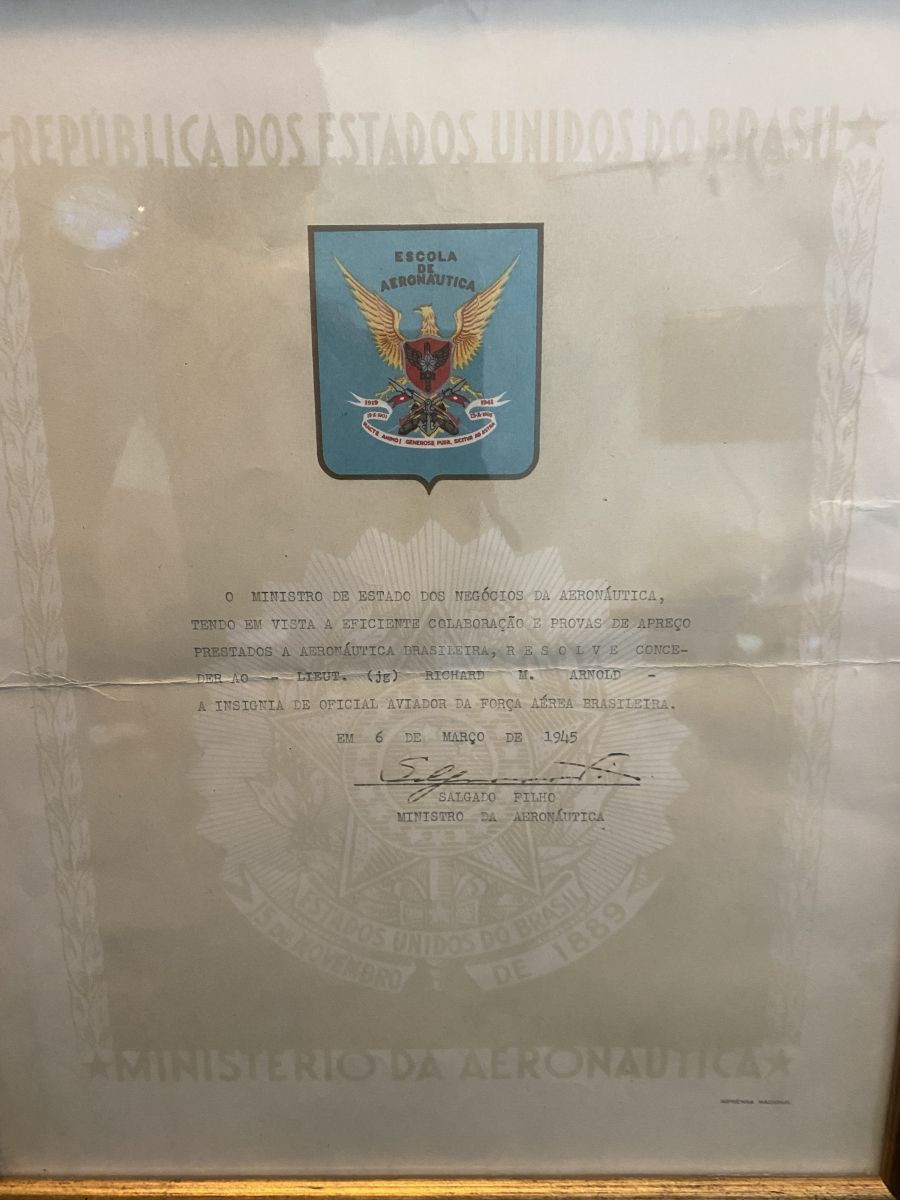

The Brazilian Air Force Certificate granted to Lt Arnold upon completion of the course administered to Brazilian pilots.

The picture above shows the ceremony of delivery of 18 PBY-5 Catalinas to the Brazilian Air Force at Galeao Airbase Rio de Janeiro early in 1945.

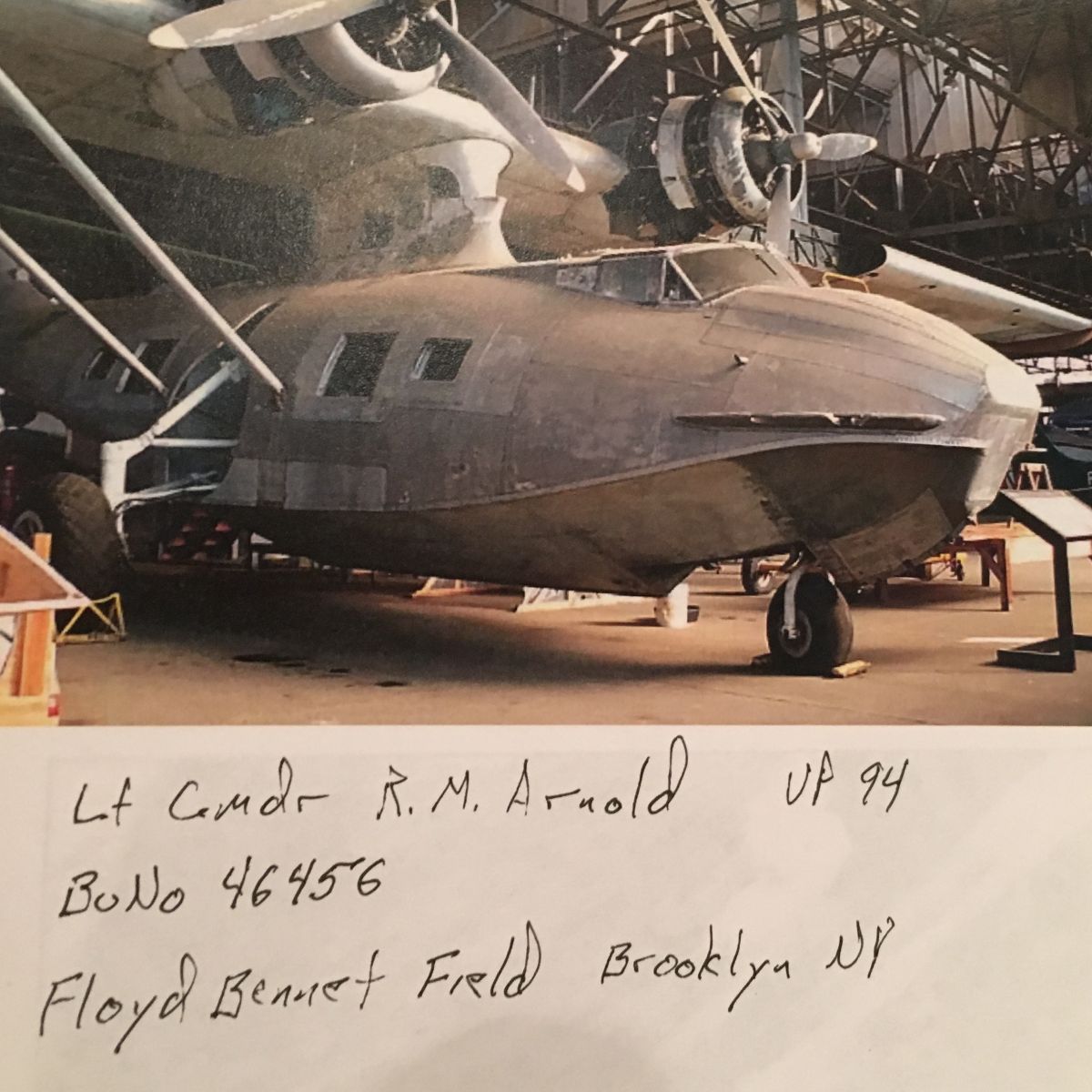

Above, one of the Catalinas Lt Arnold flew in Brazil is seen at Floyd Bennet Field awaiting restoration.