THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

34)CONCLUSION

Before the commencement of the first sustained German U-boat offensive off the South African coast, there prevailed a somewhat uninspired attitude in the Union towards ASW. The fact that the South African and British naval authorities professed that they would only become aware of the presence of U-boats off South Africa upon receipt of the first reports of their attacks, points this out to a degree. Once these attacks materialised, and upon the activation of the appropriate Allied ASW defensive measures, the Eisbär group steadily lost its initial operational edge. This advantage had, of course, been gained during their surprise attacks of October 1942.

There was a marked evolution in ASW measures employed in South African waters between October 1942 and August 1943. These measures have a direct correlation with the sharp decline in the number of merchants lost in said waters. There were several main developments concerning ASW. These involved the establishment of group sailings and escorted convoys along the Union’s coast; the provision of adequate surface and air escorts for these convoys; and the introduction of regular surface and air A/S patrols. Other signs of progress included the increasing effectiveness of the HF/DF stations in pinpointing the location of U-boats operational along coast; and the establishment of a Combined Operations Room at the Combined Headquarters in Cape Town, which formalised and centralised control over all ASW measures and operations in South Africa. Finally, combined operations were introduced from the end of 1943 with the explicit purposes of locating and destroying U-boats.

These ASW measures ensured that the UDF and the South Atlantic Station regained the operational initiative and control over South African territorial waters and the vital shipping lanes that passed through it. It is important to realise that without British materiel and operational support regarding ASW, the South African authorities could hardly have achieved any notable successes owing to a lack of trained personnel and outdated equipment. Providentially, both the UDF and the South Atlantic Station made a stark realisation. They became aware of the fact that only through a continuous process of evaluating the theoretical and operational approaches to ASW – due to the ever-changing operational exigencies – could success in the naval war against U-boats be guaranteed. The outcome was that both South African and British military personnel received constant training concerning ASW. The training often came from British A/S experts. This ensured that the personnel kept abreast of the evolution of ASW.

The best criterion by which to judge the successes of ASW in South African waters, however, remains the sinking of the three German U-boats in the Southern Oceans between 1942 and 1944. The sinkings of U-179, U-197 and UIT-22, arguably occurred at the beginning, at the height, and at the end of the German U-boat offensives in South African waters. They thus positively reflect on the vast improvements made regarding ASW is these waters. Ironically, however, these were British operational successes. No South African naval or air unit was involved in any of the three final acts that resulted in the sinkings of the U-boats in South African waters. South Africa thus wholly relied on British naval and air support to help secure its territorial waters, as well as the strategic shipping lanes that passed around its coastline.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study is to provide a critical, comprehensive analysis of the Axis and Allied maritime operations around the southern African coast between 1939 and 1945. In doing so, it introduces a fresh, in-depth discussion of the topic, based on extensive archival research in South Africa and the United Kingdom, as well as a wealth of secondary source material. The broad topic has been investigated using a number of research objectives that focussed on specific aspects related to the greater maritime war waged off the South African coast. These particular aspects encompass the rival Axis and Allied maritime strategies in the Southern Oceans, the development of the South African coastal defence system, the Axis maritime operations, the maritime intelligence war, and, finally, the anti-submarine (A/S) war waged off the southern African coast during the Second World War. This is the first study to attempt an analysis of these characteristics of the maritime war.

For the full extent of these Axis and Allied maritime strategies in South African waters to be grasped, one has to accept that shipping forms the foundation of understanding the rival maritime strategies. The availability of merchant shipping for key imports and exports to and from the Union proved crucial to the continued functioning of the South African war economy between 1939 and 1945. Sourcing this shipping, however, proved immensely problematic. This was because South Africa often desired more imports than the Allied shipping programmes could provide. The introduction of a number of control measures, such as a priority rating system and the establishment of the Combined Shipping Adjustment Board, helped to incrementally ease the Union’s wartime shipping problems to manageable proportions.

The strategic location of South Africa astride the main maritime trade routes around the Cape of Good Hope ensured that a large number of naval and merchant vessels visited its harbours throughout the war. The Union naturally had to exercise control over all the shipping which visited its ports. At the same time, it had to make adequate provision for the victualling and repair of all naval and merchant vessels calling at Union harbours. The establishment of the South African Ports Allocation Executive and the appointment of the Controller of Ship Repairs helped the South African authorities to exercise adequate control over the large numbers of naval and merchant shipping visiting its ports. The South African contribution to the larger Allied war effort in this regard continues to remain under-appreciated.

The outbreak of the Second World War coincided with the South African desire to gain complete control over its naval and coastal defences. South Africa was determined to realise this desire on both political and military levels, though the practical realities of this naval determinism only came into effect after the establishment of the Seaward Defence Force (SDF) in January 1940. The war naturally created an opportunity, and served as a catalyst, for the Union to successfully address the question of control over its naval and coastal defences. The matter of control of Simon’s Town, however, was deferred until well into the 1950s. Even though the SDF and South African Naval Forces (SANF) to a minimal degree served with exception in South Africa’s naval and coastal defence, the Union never truly exercised complete maritime control over its territorial waters. Throughout the war, South Africa had to rely on the British Admiralty for operational, technical, administrative and logistic support. This support was needed to realise and maintain command of South African territorial waters and the maritime trade routes passing along its coastline.

While the Royal Navy (RN) retained command of the high seas, it relinquished control of the South African ports and coasts to the SDF and SANF. South Africa simply wasn’t in a position to exercise any command over its territorial waters during the war. In point of fact, it was the RN that conducted the majority of offensive and defensive wartime naval operations in South African waters.

The South Africans, however, demonstrated both willingness and ingenuity to adapt to each peculiar operational circumstance. These qualities, and their ability to learn the appropriate lessons, made up for any deficiencies regarding expertise, personnel or equipment throughout the war. By August 1945, South Africa had created a comprehensive system of naval and coastal defences, which helped the Allied forces to realise command at sea in the Southern Oceans. The true measure of the effectiveness of the South African naval and coastal defences was the occurrence of the Axis maritime operations along its coastline, which reached a peak between October 1942 and August 1943.

Both the Oberkommando der Marine (OKM) and the Seekriegsleitung (SKL) realised the strategic importance of the Cape Town/Freetown shipping route. They maintained that far-flung operations in the Southern Oceans could prove feasible if there was sufficient sinking potential to justify such distant naval operations. The Axis naval forces effectively operated off the South African coast between 1939 and 1945, with the main operations occurring from June 1942 to August 1943. By the end of the war, the Axis maritime operations accounted for 158 ships sunk in South African waters. This amounted to a staggering 910,638 tons of merchant and naval shipping lost. Of this number, naval mines accounted for 1.23% (11,211 tons), raiders/warships for 13.70% (124,803 tons), and submarines for an astonishing 85.06% (774,624 tons) of all shipping lost. When the figures in South African waters are isolated, the results seem impressive. However, when compared to the global outcome of the Axis maritime operations, the sinking results in South African waters are far less significant. In fact, the losses to Axis maritime operations in South African waters form a mere 5.15% of the global losses to Axis maritime operations.

The success of the Axis maritime operations in South African waters cannot be quantified in percentages and mere tonnage lost. Axis triumphs should rather be evaluated in terms of the strategic effect that they created during the war. Their operations succeeded in causing a notable amount of inconvenience and anxiety for the Allies. Above all, the principal aim was achieved. This involved destroying shipping and forcing the adoption of convoys. The Axis powers also created a grim economic and financial set of circumstances for the Allies by forcing the deployment of strong naval forces to protect vast sea routes. From October 1942, the operational conditions in South African waters deteriorated considerably due to South African and Allied antisubmarine (A/S) operations. As a matter of fact, by August 1943, the SKL and Befehlshaber der U-Boote (BdU) ceased to consider South African waters as a viable operational area with sufficient sinking potential to justify such distant operations.

The maritime intelligence war waged in southern Africa during the Second World War informed both the Axis maritime operations and Allied countermeasures to some degree. The maritime intelligence war was, however, incredibly complex in nature, and involved multiple role-players.

The Axis influence on the maritime intelligence war in southern Africa proved negligible from the start. The initial contacts established between Germany and the Ossewabrandwag were haphazard in nature. This was principally a consequence of the German desire to establish contact with the leader of the official parliamentary opposition – D.F. Malan – rather than Hans van Rensburg. These initial contacts also had no immediate bearing on the maritime war in South African waters. It was indeed only Hans Rooseboom, and later Lothar Sittig, who had some degree of an influence on the maritime intelligence war in South Africa. Both agents at various stages passed along shipping intelligence to Berlin via the Trompke Network in Lourenço Marques, although the value of this intelligence was questionable.

Once Sittig established direct contact with Berlin, he was able to transmit both political and military intelligence without interference from the German Embassy in Lourenço Marques. Moreover, the operational value of the military intelligence passed along by Sittig to Berlin remained exceedingly questionable. This was a result of the shipping intelligence being largely outdated by the time it was transmitted to Berlin. Apart from this complication, two-way transmissions between Sittig and Berlin were only established in July 1943, shortly before the SKL and BdU ceased to consider South African waters as a viable operational area. The shipping intelligence passed on to Berlin by the FELIX Organisation after July 1943 thus held no direct operational value to Karl Dönitz and his U-boat Commanders for the remainder of the war.

The Cape Naval Intelligence Centre (CNIC) proved to be the leading role player in the Allied maritime intelligence war fought in southern Africa between 1939 and 1945. Located in Cape Town, the CNIC formed a vital link in the overall Allied maritime intelligence organisation during the war. It presided over both operational intelligence and counterintelligence in the Cape Intelligence Area. The various sub-departments of the CNIC in Cape Town worked in unison during the prosecution of the naval war. These included tracking, operational intelligence, security, and naval press relations and censorship. The “Y” Organisation in South Africa, and in particular its HighFrequency/Direction Finding (HF/DF stations), proved indispensable in pinpointing the locations of all Axis naval vessels in South African waters. It also listened in on the illicit wireless transmissions in the Union and Mozambique. The successes of the A/S operations in the Southern Oceans are without a doubt directly related to the operational successes of the “Y” Organisation.

Before the onset of the first sustained German U-boat offensive off the South African coast in 1942, there existed a clear attitude of indifference in the Union with regards to anti-submarine warfare (ASW). The fact that the South African and British naval authorities disclosed that they would only become aware of the presence of Uboats in the Southern Oceans upon receipt of the first reports of their attacks, highlights this indifference to some degree. Once these naval attacks materialised, however, and upon the activation of the appropriate Allied ASW measures, the Eisbär group steadily lost the inceptive operational advantage gained during their surprise attacks of October 1942.

Moreover, there was a growing sophistication in the ASW measures employed in South African waters between October 1942 and August 1943. These measures furthermore had a direct correlation with the sharp decline in the observed loss of merchantmen in these waters. The main developments concerning ASW were the establishment of group sailings and escorted convoys along the Union’s coast; the provision of adequate surface and air escorts for these convoys; the introduction of regular surface and air A/S patrols, and the increasing effectiveness of the HF/DF stations in pinpointing the location of U-boats operational along the coast. Additionally, the establishment of a Combined Operations Room in Cape Town formalised and centralised control over all ASW measures and operations in the Southern Oceans. The introduction of combined operations from the end of 1943 – with the explicit purpose of locating and destroying U-boats operating along the South African coast – was the final development regarding ASW in these waters.

Thanks to these ASW measures, the Union Defence Force (UDF) and the RN’s South Atlantic Station had regained the operational initiative and control over South African territorial waters and the associated vital shipping lanes by the end of 1943. However, without British materiel and operational support, the South African defence authorities could hardly have achieved any notable ASW successes. This was due to a lack of the trained personnel and their outdated equipment. The UDF and the South Atlantic Station did nonetheless make an important realisation. They understood that success in the naval war could only be achieved through a continuous process of evaluating the theoretical and operational approaches to ASW due to the ever-changing operational exigencies in the Southern Oceans. As a result, both South African and British naval personnel received constant training concerning ASW, often from British A/S experts. This ensured that they kept abreast of global developments associated with ASW.

The best measure of success regarding ASW in South African waters remains the sinking of the three German U-boats between 1942 and 1944. The sinkings of U-179, U197 and UIT-22, which arguably occurred at the start, the height, and at the termination of the German U-boat offensives in South African waters, positively reflects on the vast improvements made regarding ASW in these waters. These sinkings were, however, British operational successes, for no South African naval or air units were involved in any of the three final acts that resulted in the sinkings of these U-boats. South Africa thus wholly relied on British naval and air support to secure its territorial waters and the strategic shipping lanes that passed around its coastline.

When evaluating the all-encompassing nature of the Axis and Allied maritime operations around the southern Africa coast during the war, several concrete conclusions can be drawn. First and foremost, Neidpath was indeed correct when he stated that the three keys for continued control over the Indian Ocean was British possession of the Cape of Good Hope, Aden and Singapore. Moreover, continued Allied control over Gibraltar, Egypt and the Middle East was also crucial, largely because it guarded access over the principal maritime trade routes passing through the Mediterranean to the Atlantic and Indian oceans. The Italian entry into the war in June 1940, and the concomitant closure of the strategic Mediterranean shipping route soon thereafter, along with the Japanese and American entry into the war in December 1941, and the fall of Singapore in February 1942, combined to create a dire military, economic and logistical situation for the greater Allied war effort. Control over the remaining two keys to the Indian Ocean, Aden and the Cape of Good Hope, thus assumed levels of strategic importance, largely due to the observed interconnectivity of the Allied war effort.

Axis and Allied naval operations in the Atlantic Ocean during the ‘Battle of the Atlantic’ did also not occur in a vacuum, but had a marked influence of the naval war in the Indian and Pacific oceans at a strategic and operational level. The maritime trade routes rounding the Cape of Good Hope, which linked both the Atlantic and Indian oceans as well a key military theatres with one another, immediately became crucial to the larger Allied war effort. The Union of South Africa and the vital maritime trade routes that rounded its coast remained crucial to the Allied war effort until the reopening of the Mediterranean shipping route in 1943. The important contribution of South Africa to the larger Allied war effort in this regard, however, continues to remain underappreciated.

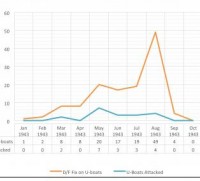

Second, the principal Axis maritime operations, which occurred between October 1942 and August 1943, actually coincided with the period during which there was a marked decline in merchant and naval vessels calling at South African ports (see Graph 1.8, page 34). The apparent sinking potential that South African waters held during 1942, and which initially prompted the OKM and SKL even to consider such distant naval operations, was thus an anomaly. In fact, the height of the sinking potential in South African waters occurred during the 1940/1941 fiscal year, when 11,082 merchant and naval vessels, totalling some 46,831,026 gross tons, called at Union ports.

Third, it remains unsurprising that the OKM and SKL failed to obtain accurate naval intelligence detailing the unique shipping conditions in the Southern Oceans. The fact that two-way transmissions between Lothar Sittig and Berlin only realised in July 1943, coupled with the questionable operational value of the naval intelligence transmitted to Berlin, serves as ample evidence to highlight the ineffective nature of the Axis intelligence network in southern Africa. The Trompke Network in Lourenço Marques, and the FELIX Organisation in South Africa, thus had a negligible impact on the Axis maritime operations in the Southern Oceans.

Fourth, even though the war served as the catalyst for South Africa to obtain complete authority over its naval and coastal defences, the Union never truly exercised total control over its maritime domain. South Africa had neither the operational capacity nor naval expertise needed to realise complete command of its territorial waters. It thus had to rely on the Admiralty for operational, technical, administrative and logistic support throughout the war. It was, in fact, the RN that conducted the majority of offensive and defensive naval operations in South African waters during the war. Nevertheless, by the end of the war, South Africa had created a comprehensive system of naval and coastal defences, which helped the Allied forces to realise its command of the Southern Oceans. More importantly, South Africa realised complete control over its maritime and coastal defences during the war.

Despite the impressive nature of the Union’s naval and coastal defences, their deterrent value throughout the war remains debatable. It is true that the Axis naval forces never directly attacked a South African port during the war. This fact should, however, preferably be ascribed to the principal aim of the Axis maritime operations in the Southern Oceans, rather than to the deterrent value of the naval and coastal defences. Moreover, when considering that neither the fixed coastal nor naval defences ever fired a shot in anger during the war, their apparent deterrent value is somewhat negated. This begs the question whether there was not an over investment in the South African coastal and naval defences during the war. The available resources might well have been applied elsewhere to better serve the Allied war effort.

Fifth, in general, however, the UDF emerged from the war far stronger and better equipped in terms of its naval and coastal defences. The Second World War, in fact, served as the catalyst for this marked change, with Britain providing key military equipment and assistance to the UDF throughout the war. The Army and the Air Force also naturally benefited from the war in terms of the procurement of modern arms and aircraft. This far-sightedness should well be accredited to Smuts, who continuously pressed for greater South African participation in the larger Allied war effort. The result of this increased participation could to a large degree be measured in the transformation of the UDF from an ageing peacetime defence force in 1939, to one that could project offensive power across the African subcontinent and further afield by the cessation of hostilities in 1945. Moreover, the wartime experience of South African sailors, airmen and soldiers served the UDF well after the war, as South Africa assumed a far greater role in safeguarding its own sovereignty.

Sixth, the success of the Axis maritime operation in the Southern Oceans remains contentious. The OKM and SKL maintained that far-flung operations in South African waters could be justified through sufficient sinking potential and operational successes. Nevertheless, the sinking results are not as convincing (see Table 3.14, page 121). There is, in fact, an apparent disconnect between the sinking potential and actual sinking results obtained by the Axis naval forces in South African waters during the war (see Table 3.14, page 121; Graph 1.8, page 34).

The success of the Axis maritime operations in South African waters is, however, best evaluated with regards to the strategic effect that it created. Moreover, these farflung operations achieved their principal aim – that of destroying merchant shipping, forcing the adoption of convoys, and creating an adverse economic and financial position for the Allies. Besides this, it also compelled the RN to deploy strong naval forces to protect vast sea global trade routes, as well as those passing around the Cape of Good Hope. As the operational conditions in South African waters steadily deteriorated during the latter half of 1942, the SKL and BdU ceased to consider South African waters as a viable operational area with sufficient sinking potential needed to justify the distant naval operations.

Seventh, the Allied intelligence network in southern Africa proved instrumental in the successful pursuit of the maritime war in the Southern Oceans. The CNIC formed an indispensable link in the overall Allied maritime intelligence organisation during the war. It did so by presiding over both operational intelligence and counterintelligence in the Cape Intelligence Area. The untiring efforts of the “Y” Organisation in South Africa during the war, prevented the Axis naval forces from ever gaining the operational upper hand in the Southern Oceans. The successes of the A/S operations in the Southern Oceans also has a direct correlation with the wartime operational successes of the “Y” Organisation in South Africa.

Finally, the sinking of the three German U-boats in South African waters between 1942 and 1944 remained the optimal way to ascertain ASW successes in the Southern Oceans. These sinkings also positively reflect on the vast improvements made regarding ASW in the Southern Oceans. It is, however, an undeniable reality that these sinkings remained British operational successes, and they should thus be evaluated as such. South Africa was entirely reliant on British naval and air support to secure its territorial waters and the strategic shipping lanes around the Cape of Good Hope. Without such support – and due to its lack of trained personnel and outdated equipment – the South African military authorities could hardly have achieved any significant ASW successes. The evolution of ASW measures in the Southern Oceans ultimately culminated in denying the Axis naval forces from obtaining the operational initiative and control in South African waters.

In conclusion, this dissertation demonstrates the all-encompassing nature and extent of the maritime war waged off southern Africa during the Second World War. This study further finds that the Axis and Allied maritime operations in the Southern Oceans were extremely complex in nature, especially when considering the several strategic, military and economic aspects that underpinned them. In gaining an understanding of these complex operations, the dissertation draws together several of the interrelated aspects that have formed the foundation of the maritime war waged off the South African coast. In doing so, this study builds on several previous studies. These analyses have generally not succeeded in recognising the apparent interrelatedness. Instead, they have provided only a compartmentalised discussion on single aspects associated with the maritime war.

This study is novel in that it provides an unrivalled analysis of the Axis and Allied maritime operations in South African waters during the war. While addressing several previously disregarded aspects of the South African involvement in the Second World War, the dissertation definitely refocuses attention on the importance of the maritime trade routes passing along the South African coastline. The current importance of these trade routes, along with the accompanying issues of maintaining command at sea along the entire African coastline, are demonstrated by growing concerns over maritime insecurity in the Southern Oceans during the twenty-first century.