THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

33)REDUCED SINKINGS, NAVAL WAR ENDS

5.3 Reduced sinkings, combined operations, and the culmination of the naval war

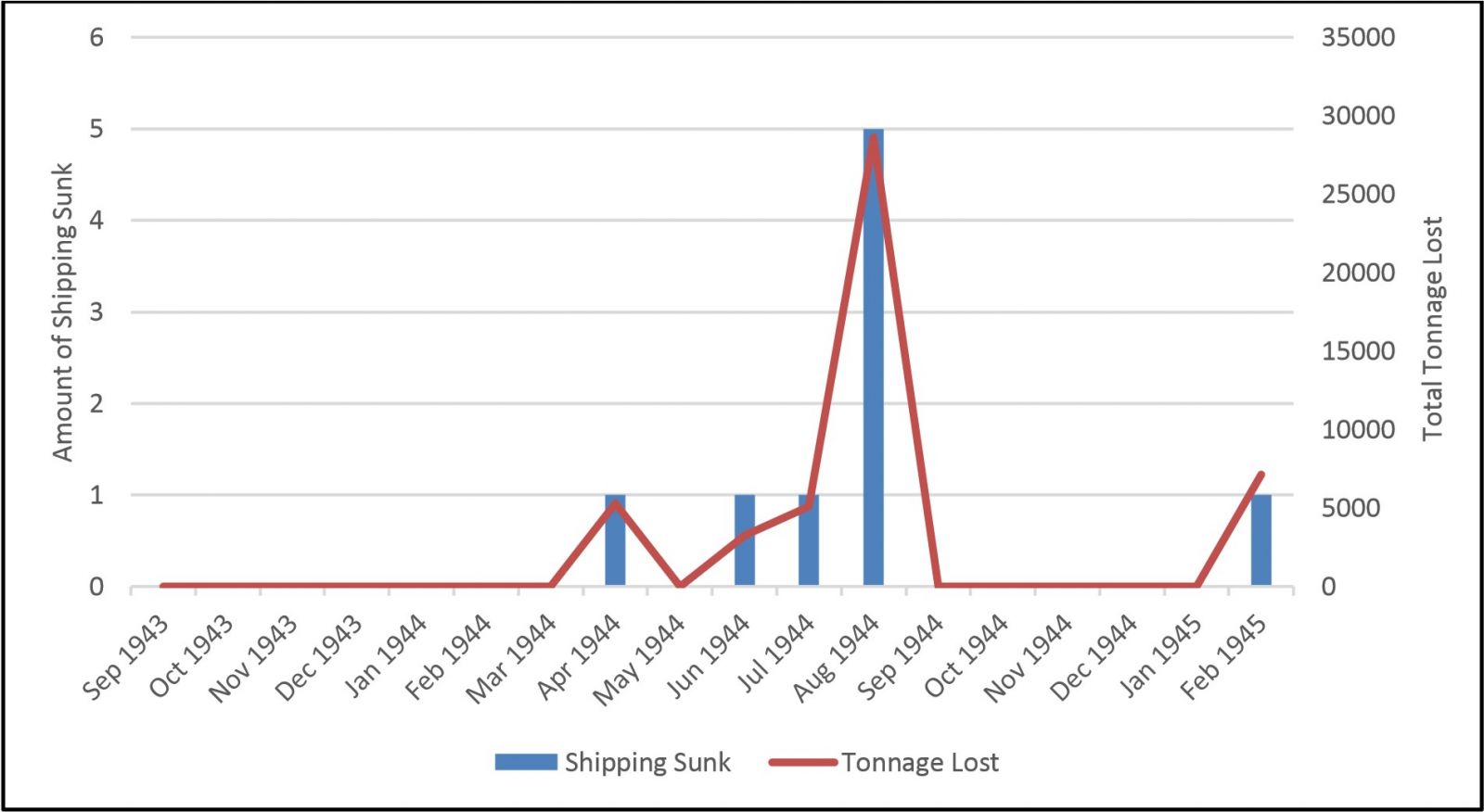

The BdU ceased to regard the waters off the South African coast as a viable operational area from September 1943. It was initially argued by the BdU that the submarines earmarked for offensive operations in the Far East would inevitably pass through South African waters before reaching their far-eastern bases at Penang and Surabaya. This would provide the U-boats with ample opportunity to attack Allied merchant shipping along the South African coastline, which would take place during their journeys to and from their new operational areas. This line of argument is more or less accurate. However, one cannot separate the disregard shown by the BdU for the South African coast as an operational area from the drastically improved ASW measures in these waters. In point of fact, the ASW measures in place in the Southern Oceans by the latter half of 1943 had been so efficient that the U-boats found it increasingly difficult to operate successfully against merchant shipping. There were, however, exceptions to the rule, with nine merchantmen lost off the South African coast between March 1944 and February 1945 (see Graph 5.6).[1]

Stephen Roskill has a hypothesis about the triumph in the war against the Uboats. He asserts that the decisive victory was the result of the adoption of the largely defensive strategy of sailing merchant shipping in convoys, and providing such convoys with strong surface and air escorts. He further states that the British desire to assume the offensive against the U-boats during the first two years of the war was not well thought through and ultimately disastrous. The persistent employment of a large number of RN vessels to hunt U-boats in the vast oceans spaces, he argued, was counterproductive. This was because the vessels could do better by providing escort duties to the large number of ocean-going convoys. It is a known fact that these hunting groups achieved negligible successes during the naval war, especially since it led to the dispersal of the slender naval resources available to the Allies for ASW.

Besides, the dispersal of these slender resources resulted in the ineffective escorting of convoys, which naturally led to heavy operational losses on the part of merchant shipping in particular. Furthermore, several tactical opportunities were missed to engage the Uboats which attacked the convoys. The failure to enter into combat was due to the lack of sufficient escort forces. The initial belief that bomber aircraft could largely defeat the U-boat peril through strategic bombing campaigns was misconstrued. This was so particularly since focusing aerial attacks against the Axis submarine bases – rather than protecting and escorting convoys on the open sea – did not prove to yield the required operational results during the war. According to Roskill, the most effective way of defeating the U-boat peril was to focus the operational attention on the area in which the U-boats were most likely to attack merchant shipping, and then launch a series of combined operations aimed at locating and destroying said U-boats.[2]

Graph 5.6: Decreased merchant shipping losses in South African waters, 1943-1945[3]

From the end of August 1943, the primary concern of the South Atlantic Station was the interception and destruction of U-boats travelling between Germany and the Far East as they rounded the Cape of Good Hope. Tait and his staff realised that the chances of success in the pursuit of this endeavour was negligible. Yet they did profess that certain operational exigencies experienced by the U-boats while traversing the Cape of Good Hope worked in their favour. The large operational distances between Germany and the Far East, as well as the small reserve of fuel carried by each U-boat, meant that even moderate damage caused to a U-boat during an attack could ensure eventual operational results. Even if the A/S hunting forces did not obtain a straightforward kill, any attack on a U-boat ensured that it expended extra fuel. All told, the essence of these attacks was to harry the U-boats to a point of exhaustion. GordonCumming makes an interesting assertion. He maintains that while both SANF and RN vessels formed part of each of the carefully planned combined operations in South African waters, it was only SAAF and RAF aircraft that managed to locate the U-boats and attack them during the course of these operations. Nevertheless, the combined operations required a great deal of unity of action and purpose to ensure their success.[4]

By the latter half of 1943, the SAAF and RAF pilots involved in A/S sorties around the South African coast became somewhat adept at the tactical and operational intricacies that underpinned an aerial attack on a U-boat. A Cape Fortress Intelligence Summary of December 1942 highlights the fact that a pilot about to strike a U-boat has only a small window of time during which to decide how to approach the attack.

The intelligence summary identified six important factors that pilots had to consider during an assault on a U-boat. First, within fifteen seconds of diving, the submarine would have travelled at least 150 feet. Second, fifteen seconds after diving, the submarine would be at an average depth of 45 feet. Third, the conning-tower would have deviated a distance of 10 feet to either side, with the turning circle of the U-boat becoming sharper as time lapses. Fourth, the psychological reaction of a U-boat skipper is to crash-dive and turn either to port or starboard in an effort to put the greatest distance between him and the aircraft. Fifth, submarines are more likely to crash-dive as opposed to normal dive upon attack. And last, as a submarine is approximately 200 feet long, 20 feet wide, and 16 feet high, aircraft should set their depth charges to explode at a depth of 50 feet and then drop them at 30 foot intervals in order to ensure success during an attack. If pilots kept the above six factors into account, they were only required to worry about the time it would take their aircraft to reach the spot where the U-boat had dived, as this naturally affected the position where they could drop their depth-charges. The intelligence summary finally cautioned the pilots that not all U-boats dived when attacked by aircraft and that some preferred to fight it out with the aircraft using their AA guns.[5]

Under the auspices of the Commander Coastal Air Defences, A/S training for SAAF pilots in 1943 became more practical. The unique operational conditions along the South African coastline were a primary factor of this. In an A/S lecture delivered by a certain Wg Cdr Lombard in February 1943, the South African pilots were reminded of the importance of keeping a constant visual lookout while on A/S patrols. Lombard encouraged the pilots to establish a definite lookout system among their crews and to rotate the member on lookout every 30 minutes to avoid fatigue. The lecture furthermore dismissed the idea that locating a U-boat came down to the individual luck of each aircraft crew. He reminded the pilots of that which experience had proven: that the most effective aircraft in terms of ASW were those whose crews were the most efficient and well-trained. The lecture further suggested that aircraft in patrols aimed at locating U-boats should fly at a maximum height of 5,000 feet, and depending on cloud cover, adjust their height to fly just below it. Pilots were also encouraged to use cloud cover to their advantage, and conceal their impending attack by only breaking cover two miles from the U-boat. The highly specialised nature of ASW, in general, was once more emphasised by Lombard, while he cautioned the pilots to remain continuously aware of the seriousness of the U-boat peril along the South African coast. Lombard, in conclusion, wished the pilots ‘Good Hunting’, and stated that “success will be yours if you keep yourself in constant training.”[6]

The series of combined operations launched in South African waters from the latter half of 1943 arguably heralded in the culmination of the A/S operations off the South African coast for the remainder of the war. Between November 1943 and August 1944, there were at least eight such combined operations launched with the sole intention of locating and destroying U-boats traversing the Cape of Good Hope. Throughout this period, both South African and British naval, air and ground forces cooperated in the execution of the combined operations. The individual operations were: BARRAGE[7] (9 Nov 1943); BUSTARD[8] (3 Dec 1943); WOODCUTTER[9] (4 Jan 1944); WICKETKEEPER[10] (8 Mar 1944); THROTTLE[11] (31 May 44); STEADFAST[12] (12 Jun 1944); TRICOLOUR[13] (5 Jul 1944); and VEHEMENT[14] (4 Aug 1944) (see Table 5.4). These operations were the result of the increasing successes evolving from the interception of wireless transmissions of the U-boats by the HF/DF stations in the Union. Of these eight operations, only two, WICKETKEEPER and TRICOLOUR, managed to locate and engage U-boats.[15] A detailed discussion of Operation WICKETKEEPER in particular, will reveal the unprecedented success of the combined operations along the South African coast during the war. WICKETKEEPER was the only one of the operations during which a U-boat was successfully located, tracked, attacked and sunk.

|

Operation WICKETKEEPER |

Operation TRICOLOUR |

|

8-11 March 1944 |

5-8 July 1944 |

|

One to three German U-boats |

German U-boat |

|

39°S;33°E (westbound) 35°S;2215’°E (westbound) 38°30’S;08°30’E (southbound) |

32°00’S;36°30’E |

|

Location + destruction of U-boats |

Location + destruction of U-boat |

|

HMS Lady Elsa HMS Lewes HMS Norwich City HMSAS Southern Barrier HMSAS Roodepoort |

HMS Pathfinder HMSAS Turffontein HMSAS Immortelle HMSAS Sonneblom HMSAS Vereeniging |

27 TBR SAAF Sqn (Phesantekraal) 262 RAF Sqn(Langebaan) |

RAF Catalinas SAAF Venturas |

|

Yes, visually and through D/F on several occasions |

Yes, visually and through D/F |

|

Yes, U-178 depth-charged by a Ventura on 8 March, and UIT-22 strafed and depthcharged throughout 11 March |

Yes, engaged on two separate occasions by aircraft during which U-boat was strafed and depth-charged |

|

UIT-22 successfully sunk |

Unidentified U-boat severely damaged, not sunk |

Table 5.4: Comparison between Operations WICKETKEEPER and TRICOLOUR[16]

By the beginning of March 1944, the operational conditions off the South African coast once more changed. Both the UDF and South Atlantic Station had been lulled into a false sense of security since September 1943. As a result of this feeling of safety, there was a marked reduction in the number of coastal air patrols along the seaboard. Independent sailings between Cape Town and Durban were also reintroduced. The operational conditions, however, soon underwent change. In November 1943, the BdU ordered U-178 (Spahr), then based at Penang in the Far East, to return to Europe. It was to expend its torpedoes on the voyage home across the Indian Ocean. By the end of December, U-178 had refuelled from the Charlotte Schliemann 200 miles to the south of Mauritius. It had then travelled onwards with the explicit aim of making good a rendezvous with UIT-22 (Wunderlich) to the south of Cape Town. While journeying south, American aircraft attacked UIT-22 near Ascension Island and caused considerable damage and a loss of fuel. The planned meeting between U-178 and UIT-22 was the result of this attack, with Spahr ordered to refuel Wunderlich’s damaged Uboat.[17

Fig 5.7: Karl Wunderlich – the commander of UIT-22[18]

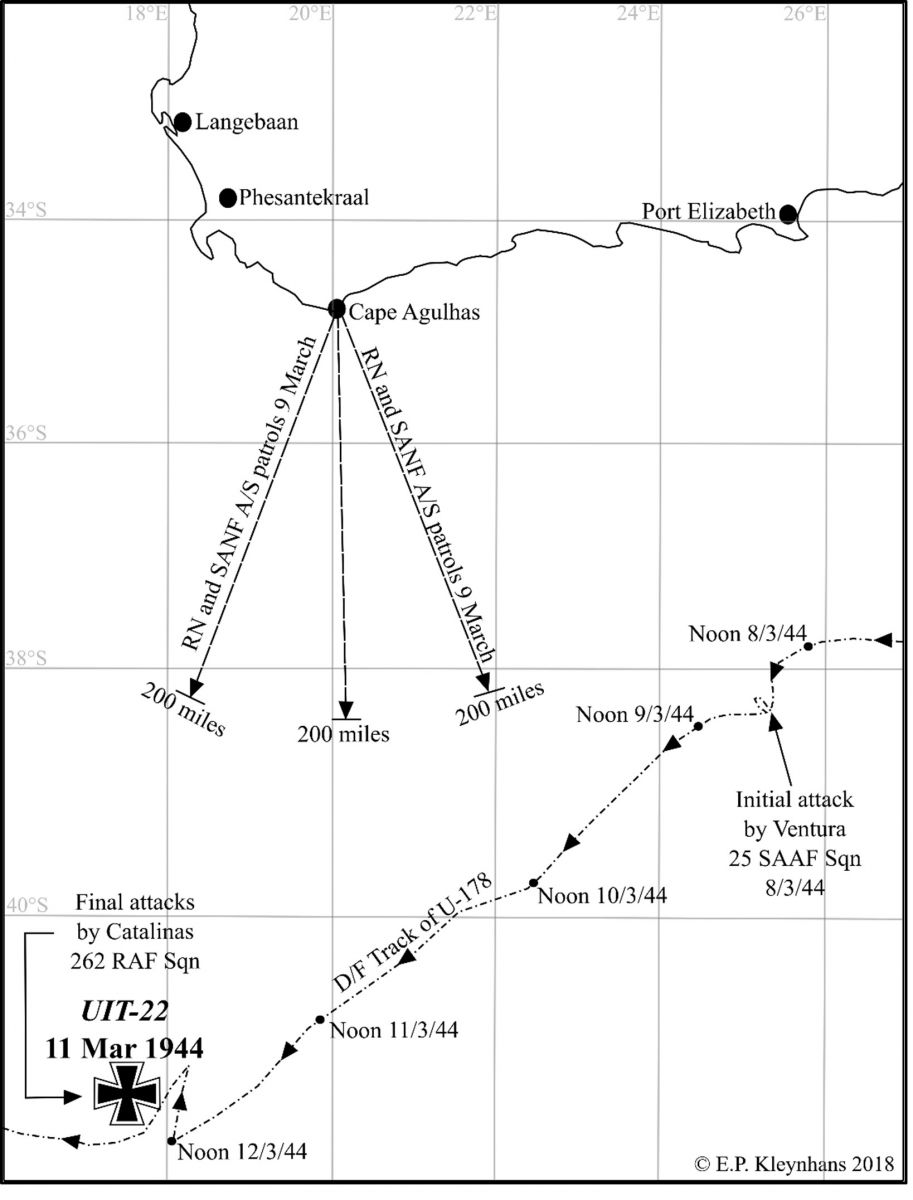

On 5 March, the HF/DF stations in the Union established such a good fix on the indiscriminate wireless transmissions of U-178, that the UDF and South Atlantic Station ordered an immediate A/S operation with the sole aim of locating and destroying the westbound U-boat. The combined operation, with the appropriate codename WICKETKEEPER, started on 8 March. It saw sterling cooperation between both British and South African naval, air and ground forces (see Map 5.5).[19] Two SANF vessels, HMSAS Southern Barrier and HMSAS Roodepoort, immediately left Cape Town and proceeded to patrol an area roughly 140 miles south-south-west of Cape Agulhas. Concurrently, HMS Lady Elsa, HMS Lewes and HMS Norwich City extended their patrol 60 miles further south. Meanwhile, several SAAF and RAF aircraft flew A/S patrols in the hope of locating U-178. On 8 March, a Ventura from No. 25 SAAF Squadron sighted U-178 approximately 350 miles to the south of Port Elizabeth. The aircraft attacked U178 with five depth-charges after it had dived. The U-boat, however, received no damage, and Spahr continued his journey to the intended rendezvous with an increased sense of vigilance after the attack.[20]

Map 5.5: Operation WICKETKEEPER and the sinking of UIT-22

The staff of the South Atlantic Station correctly judged that the intensive aerial patrols would coerce Spahr into travelling further away from the coast. They thus ordered all aircraft involved in WICKETKEEPER to extend their patrols 60 miles further south and west over the following days. On the morning of 11 March, a Catalina from No. 262 RAF Squadron operating out of Langebaan, spotted something 600 miles to the south of Cape Point. The aircraft, piloted by Flt Lt F.T. Roddick, identified UIT-22, and not U-178 as expected. Roddick initiated an attack on UIT-22 post-haste. Wunderlich, showing no intention to dive, responded with a salvo of anti-aircraft fire from his Uboat. During the ensuing attack, Roddick managed to drop five depth-charges on UIT-22 which all met their intended target. While listing heavily, UIT-22 submerged amidst a large patch of oil. After a few minutes, the U-boat once more surfaced, but accurate machinegun fire from Roddick compelled Wunderlich to dive once more. During the attack, Roddick’s Catalina received some damage from the accurate anti-aircraft fire laid down by Wunderlich, and he soon had to return to base. Two more Catalinas relieved Roddick, and when UIT-22 surfaced for one last time, Flt Lt A.H. Surridge and Flt Lt E.S.S. Nash simultaneously attacked the U-boat with depth-charges and machinegun fire.[21] The fate of UIT-22 was hence sealed. Spahr, in a fitting conclusion, best described the deteriorating operational conditions for the U-boats in South African waters when he answered his own question: “Where is one safe nowadays on the high seas? Nowhere.”[22]

Fig 5.8: Flt Lt Nash homing in on UIT-22 during the final attack[23]

The fact that only nine merchantmen were lost in South African waters between April 1944 and February 1945 bears testimony to the efficiency of the combined operations in the Southern Oceans, particularly since these operations removed the operational initiative from the U-boats. For the remainder of the war, A/S activities off South Africa were limited to the combined operations mentioned before. Moreover, the Admiralty, in particular, was very pleased with the successes of ASW off the Union’s coast. In a mid-1944 message to Tait, after the apparent success during Operation TRICOLOUR, they stated “… [as] this is the second consecutive operation in which a Uboat passing through your area has been successfully located and probably destroyed… [it] reflects [positively on] the high standard of operational control.”[24] During the remainder of the war, the South Atlantic Station busied itself with continuous training and A/S exercises involving all RN and SANF vessels and shore establishments, as well as RAF and SAAF squadrons.[25]

It is Pierre van Ryneveld, however, who has the final word on the sterling cooperation that existed between the South Atlantic Station and the greater UDF in the pursuit of the ASW off the South African coast between 1942 and 1944. In a personal letter to Tait, shortly before his departure as C-in-C South Atlantic Station, Van Ryneveld writes:

I wish to convey the deep appreciation of the SANF for your generous tribute. In the relinquishment of your command the SANF feel that they are indeed losing a friend whose sympathetic guidance has been of inestimable value to the service. I cannot let this opportunity pass without paying tribute to your services to the UDF from the Army and Air Force angle. I am not unmindful of the fact that it was due entirely to your wisdom and initiative that the Combined Headquarters of Coastal Areas was brought into being. It is this step that proved such a major factor in the cooperation and smooth working of the combined staffs of the Royal Navy and Coastal Area of the UDF, and [which has] been instrumental in promoting the general efficiency in guarding the coasts of the Union.[26]

[1] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 220, File: Union War Histories Translations 14a. U-boat Operations of the Axis Powers in S.A. Waters compiled by Dr Jurgen Rohwer, 1954; Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 238-255.

[2] Roskill, The War at Sea: Volume I – The Defensive, pp. 10-11.

[3] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945.

[4] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 240; Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, p. 89.

[5] DOD Archives, CFAD, Box 12, File: Cape Fortress Intelligence Summary. Cape Fortress Intelligence Summary No. 10, 4 Dec 1942; DOD Archives, CFAD, Box 12, File: Attacks on U-boats and submarines. Circular from CCAD to Fortress Command and SAAF squadrons regarding U-boat attacks, 12 Jan 1943.

[6] DOD Archives, Commander Fortress Air Defence (CFAD), Box 12, File: Attacks on U-boats and submarines. Lecture on A/S warfare by Wing Commander Lombard, 22 February 1943.

[7] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 125, File: Barrage II. Circular from C-in-C South Atlantic to GOC Coastal Area re Barrage II, 24 Nov 1943.

[8] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 125, File: Barrage II. Operation Bustard ops order, 27 Nov 1943.

[9] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 125, File: Woodcutter. Operation Woodcutter ops order, 1 Jan 1944.

[10] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 125, File: Operation Wicketkeeper. Operation Wicketkeeper, 8 Mar 1944.

[11] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 126, File: Operation “Throttle”. Operation Throttle ops order, 30 May 1944.

[12] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 126, File: Operation “Steadfast”. Operation Steadfast ops order, 12 Jun 1944.

[13] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 126, File: Operation Tricolour (location + destruction Uboat). Message from Admiralty to C-in-C SA re Operation Tricolour, 25 Jul 1944.

[14] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 123, File: Operation Vehement. Operational order for Operation Vehement, 5 Aug 1944.

[15] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 89-91.

[16] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 125, File: Operation Wicketkeeper. Operation Wicketkeeper, 8 Mar 1944; DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 126, File: Operation Tricolour (location + destruction U-boat). Message from Admiralty to C-in-C SA re Operation Tricolour, 25 Jul 1944.

[17] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 242-243.

[18] https://uboat.net/men/commanders/1383.html (Accessed 6 May 2018).

[19] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 125, File: Operation Wicketkeeper. Operation Wicketkeeper, 8 March 1944; DOD Archives, CGS War, Box 265, File: Sitreps coastal area. Most secret Sitrep from Dechief Cape Town to Coastcom, 7 Mar 1944; DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 125, File: Operation Wicketkeeper. Messages and Sitreps concerning Operation Wicketkeeper, Mar 1944.

[20] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 125, File: Operation Wicketkeeper. Operation Wicketkeeper, 8 Mar 1944; DOD Archives, SAAF War Diaries, Box 125, File: A3 (25 Sqdn Jul ’43 – Mar ’44). 25 Squadron SAAF War Diary Mar 1944; DOD Archives, SAAF War Diaries, Box 125, File: A3 (25 Sqdn Jul ’43 – Mar ’44). 25 Squadron SAAF War Diary Mar 1944, Secret UBAT report (Appendix B).

[21] DOD Archives, SAAF War Diaries, Box 124, File: A4 (23 Sqn Jan–Dec 1944). 23 Squadron SAAF war diary Mar 1944; DOD Archives, SAAF War Diaries, Box 127, File: D2 (262 Squadron Sept 42 – May 44). 262 Squadron RAF war diary Mar 1944; DOD Archives, SAAF War Diaries, Box 127, File: D2 (262 Squadron Sept 42 – May 44). 262 Squadron RAF war diary Mar 1944, Secret UBAT report – Flt Lt Roddick (Appendix); DOD Archives, SAAF War Diaries, Box 182, File: A1 (SAAF war diary CCAD). CCAD coastal area headquarters war diary Mar 1944; DOD Archives, SAAF War Diaries, Box 122, File: A4 (22 Sqdn Jan – May 1944). 22 Squadron SAAF war diary Mar 1944; Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 243–244.

[22] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 245.

[23] DOD Archives, Photographic Repository. 781004773 – F/Lt E.S.S. Nash attacking U-Boat Uit22 with his Catalina Aircraft.

[24] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 126, File: Operation Tricolour (location + destruction Uboat). Message from Admiralty to C-in-C SA re Operation Tricolour, 25 Jul 1944.

[25] TNA, ADM 1/17587, A/S Organisation in South Africa. Report on the A/S Organisation in South Africa by Lt Cdr R.N. Hankey, 16 Apr 1945.

[26] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 123, File: Organisation – General. Personal correspondence from CGS to C-in-C South Atlantic, 2 Jun 1944.