THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

32)DEF MEASURES LESSONS LEARNED

.2 Defensive measures, lessons learned, and an operational success

It was the notable successes achieved by the Eisbär group during October 1942, which prompted the BdU to dispatch several more U-boats to operate in South African waters. These U-boats operated off the east coast of South Africa between Durban and Lourenço Marques and were particularly successful. By the end of November, the Seekriegsleitung (SKL) had ordered the remaining U-boats operational off southern Africa to return to the North Atlantic, to help oppose the American landings in North Africa during Operation Torch. The BdU had, however, succeeded in proving to the SKL that operations as far south as the waters off Cape Town were possible, and that such undertakings could yield good sinking results. Between October and December, eight Uboats sunk 53 Allied merchant ships, for the loss of only one U-boat. These impressive results prompted the SKL to order the BdU to send a fresh batch of U-boats to operate off Cape Town at the start of 1943. The aim was to achieve similar sinking results.[1]

The Seehund group arrived off Cape Town during February 1943, though their sinking results were virtually negligible for its entire operational period. Between 10 February and 2 April, the six U-boats attached to the Seehund group only managed to sink a total of seventeen merchant ships in South African waters. The operational results of the Seehund Group were thus inauspicious, although no U-boat was lost during this period. From April onwards, the BdU intermittently dispatched U-boats to operate off the southern African coast, which on occasion were moderately successful. The U-boats were also increasingly active towards the east coast of South Africa during the course of 1943. They operated in a quadrant that extended from Durban to Lourenço Marques, the Mozambique Channel, Mauritius and Madagascar. Between 18 April and 17 August, these U-boats accounted for 27 merchants sunk, with the loss of only one U-boat recorded towards the end of August. For the remainder of the war, however, the BdU ceased to regard the area off the South African coast as a viable working area. As an alternative, it argued that the U-boats earmarked for operations in the Far East had ample opportunity to attack Allied merchant shipping off the South African coastline while journeying to and from their new operational areas.[2]

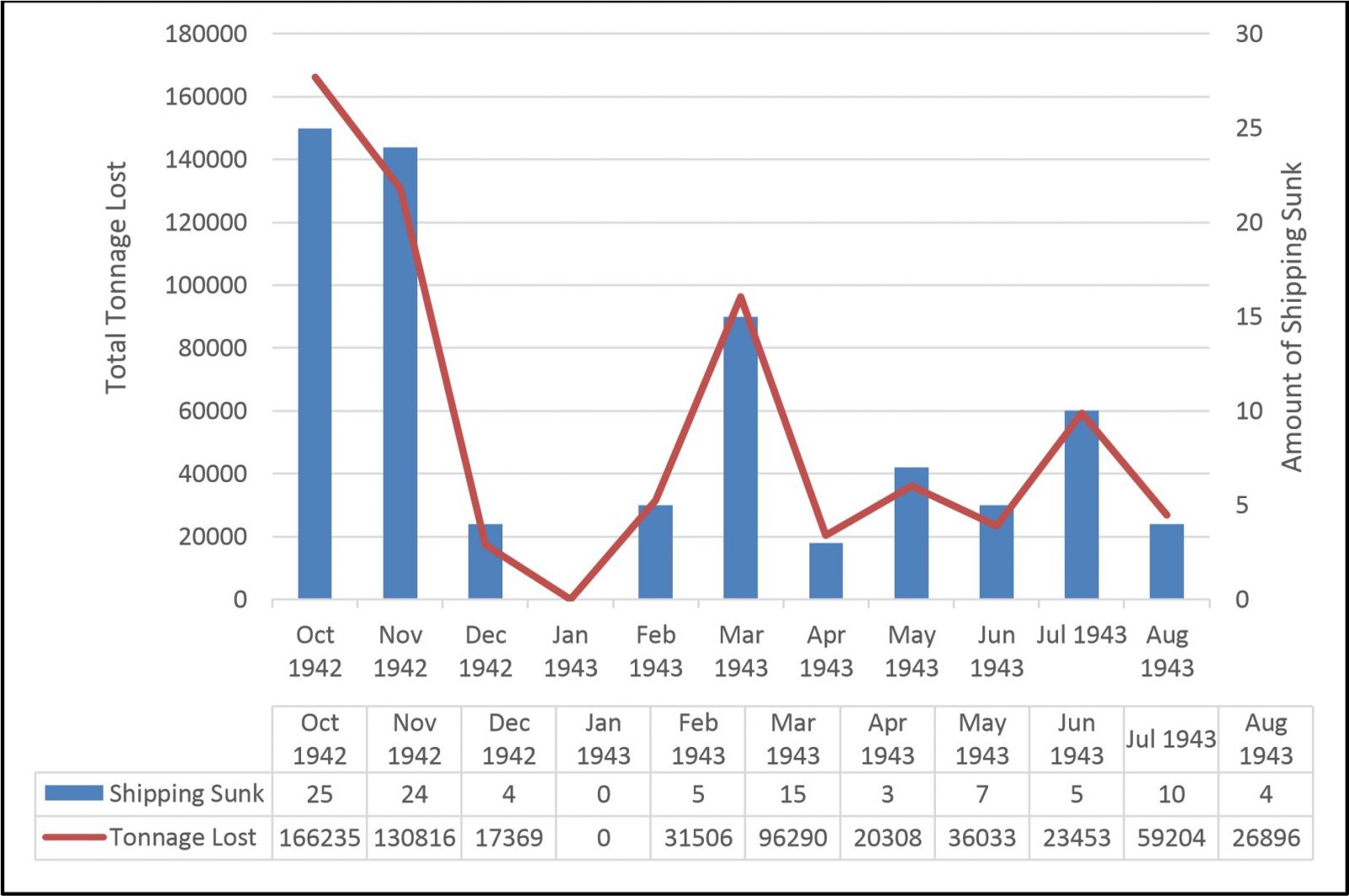

Graph 5.1: Decreasing merchant shipping losses in South African waters, 1942-1943[3]

It is evident that there was a drastic change in the operational conditions in South African waters from October 1942 to August 1943. Both the South African and British naval authorities adopted a number of stringent ASW measures aimed at curtailing the losses of merchant shipping around the South African coast. The steady decline in the number of merchant shipping lost off the South African coast during the first months of 1943 has a direct correlation with the improved ASW measures implemented after the first U-boat attacks of October 1942 (see Graph 5.1). There were several so-called ‘lessons learnt’ during the initial German submarine operations off South Africa. These allowed both the UDF and the South Atlantic Station to evaluate their initial response and implement improved ASW measures to prevent the same situation from reoccurring. In this regard, the surprise attacks launched by the Eisbär group, along with the South African and British response, served as the nadir of ASW in South Africa during the war. The implementation of the following four ASW measures best explains the decrease in the number of merchant sinkings in these waters.

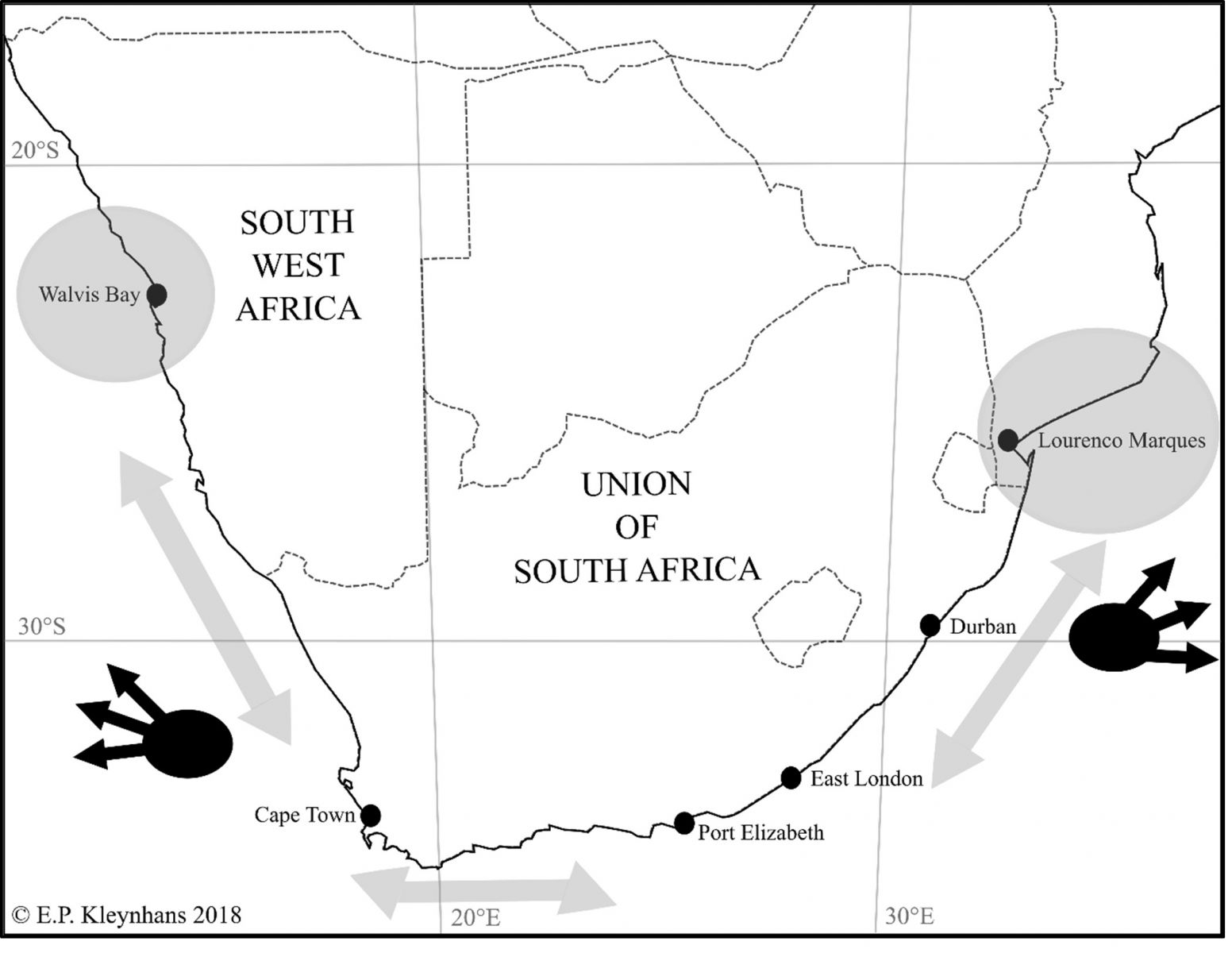

Firstly, following the opening attacks of the Eisbär group, the Headquarters of the South Atlantic Station immediately established group sailings for all outgoing merchant vessels travelling along South Africa’s west coast. Inbound merchant shipping, however, mostly sailed independently, and formed the mainstay of the subsequent vessels sunk in said waters.[4] By March 1943, Tait and his staff had divided the problem of trade protection in South African waters into two broad categories (see Map 5.2). The first category involved the protection of slower moving merchant vessels travelling along the South African coast. Tait and his staff decided to use Walvis Bay as an assembly port for all eastbound merchant shipping approaching the South African coast. This would afford the vessels maximum protection.

The Admiralty had initially hoped to form all eastbound vessels travelling to South Africa from South America and along West Africa into escorted convoys. Such a measure, however, proved unfeasible. Once the merchant shipping arrived at Walvis Bay, it travelled in a coastal convoy to either Cape Town, Durban or one of the other Union ports. The eastbound merchant vessels destined for other distant ports travelled in escorted convoys to a deep sea dispersal point, either off Cape Town or Durban. After this, they continued their onward journeys independently. Tait and his staff utilised Lourenço Marques as a holding and bunkering port – as well as a convoy assembly point – for all westbound merchant shipping approaching South African waters. A coastal convoy thus operated between Lourenço Marques and Durban for all westbound shipping, under the nominal protection of both surface and air escorts. The westbound shipping destined for ports outside the Union, travelled in a convoy to a deep sea dispersal point off Walvis Bay, whereafter the vessels continued their journeys independently.[5]

The second category which Tait and his staff had to consider, involved the socalled ‘special ships.’ The special ships comprised of all troop transports, important naval vessels and all other shipping whose great speed precluded their inclusion into the ordinary slow convoys. Such eastbound vessels approached the South African coast from varying positions, with air escort provided at the earliest possible time. Most of this shipping formed into convoys at Saldanha or Cape Town and travelled under escort to a deep water dispersal point to continue their onward journey. The vessels that proceeded along the South African coast sailed independently, with a dedicated surface and air escort. All westbound shipping either first called at Durban for logistical purposes, or travelled directly to Cape Town with an air escort provided as soon as it was available. Those calling at Durban sailed independently along the South African coast with a surface and air escort African coast.

Map 5.2: Convoy assembly points, deep sea dispersal points, and the major convoy routes along the South African coast

This particular convoy system remained in use along the South African coast until 16 September 1943. After this point, the use of convoys temporarily ceased owing to a decrease in merchant sinkings along the South African coast. The resurgence of Uboat attacks in the South Atlantic and the Indian Ocean in 1944 prompted Tait to once more reinstate convoys in South African waters on 26 March that year. This was, however, only a temporary measure, and shipping soon again travelled independently in Union waters.[7]

|

Number of Convoys |

Monthly Total |

|

|

Walvis Bay to Cape Town |

4 per month |

44 merchant vessels |

|

Cape Town to Durban |

4 per month |

48 merchant vessels |

|

Cape Town to deep sea dispersal |

6 per month |

20 merchant vessels |

|

Durban to deep sea dispersal |

8 per month |

144 merchant vessels |

|

Durban to Cape Town |

4 per month |

36 merchant vessels |

|

Cape Town to Walvis Bay |

4 per month |

45 merchant vessels |

|

Durban to Lourenço Marques |

4 per month |

12 merchant vessels |

|

Lourenço Marques to Durban |

4 per month |

12 merchant vessels |

|

Total |

38 convoys per month |

361 merchant vessels in convoy |

Table 5.2: Convoys operational in South African waters, 1943-1944[8]

Secondly, in theory, the adoption of convoys seemed the ultimate answer for ensuring the protection of seaborne trade around the South African coastline. In practise, however, the afore-mentioned convoys required both a surface and air escort in order to ensure maximum protection from U-boat attacks. By March 1943 the South Atlantic Station estimated that it needed at least eight naval escort groups to provide the required defensive protection for the convoys operational off South Africa (see Table 5.2). At the bare minimum, Tait and his staff predicted that the adequate protection needed by each convoy was at least two corvettes and three trawlers. At that stage, the South Atlantic Station could only account for seven corvettes and 21 trawlers. This figure included a number of naval vessels attached from the Eastern Fleet to the South Atlantic Station for service in South African waters. To meet the minimum requirements of escorts per convoy, Tait and his staff were thus short of nine corvettes and three trawlers. Alarmingly, the estimated escorts did not include any provision for the protection of special ships or troop convoys. Destroyers usually provided such protection. The South Atlantic Station was, however, dependent on the Eastern Fleet and the West Africa Station to provide the required naval vessels in this regard. Tait subsequently requested the Admiralty to reinforce the South Atlantic Station with nine corvettes, three trawlers and six destroyers.[9]

These reinforcements were slow to materialise. But the detachment of several larger SANF A/S vessels to South Atlantic Station at the end of 1942 to assist in escort duties drastically strengthened Tait’s defensive capabilities (see Graph 5.2). As from January 1943, one of the five escort groups operational along the South African coast was the sole responsibility of the SANF A/S vessels. These vessels rendered valuable service, and mainly escorted ships between Cape Town and Durban. Following the introduction of group sailings between Durban and Mombasa after September 1943, the South African A/S Vessels also rendered escort work along the east coast of Africa. For the next eighteen months, the South African A/S vessels formed part of the 3rd and 4th Escort Groups and rendered sterling work throughout without encountering any enemy contacts.[10] By the end of July 1943, the strength of the escort vessels available to Tait marginally increased to 33. These naval vessels included eleven corvettes and 22 trawlers.

Graph 5.2: Total number of convoys, including average number of ships and escorts per convoy, in South Africa waters, Mar-Aug 1943[11]

The strength of the escort force further increased after the arrival of nine more frigates in the same month. The quality of the escort vessels was, however, dubious, as many of the vessels arrived at the South Atlantic Station with significant defects and with antiquated ASW equipment. Throughout 1943 and 1944 the strength of the escort force fluctuated, especially after the reopening of the Mediterranean for merchant shipping in August 1943.[12]

Fig 5.5: An RAF Catalina on an anti-submarine patrol off the South Africa coast[13]

Thirdly, the provision of air escorts further helped to ensure the protection of seaborne trade, as well as naval vessels, travelling around the South African coast during the war. Aircraft from the RAF, as well as the FAA, increasingly assisted the SAAF in this regard from the end of 1942. As the maritime war continued along the South African coast throughout 1943, the South African contribution in lieu of the provision of coastal air escorts notably increased.

A number of RAF Catalina squadrons, which principally operated from Langebaan and St Lucia, were utilised in all long-range escort work. At times, the RAF Catalinas made use of Durban and Kosi Bay as well, with several aircraft also operating from inland aerodromes located at Darling near Cape Town and St. Albans near Port Elizabeth. All short-range escort work remained the responsibility of the SAAF Ventura squadrons operating from Darling, St. Albans, Walvis Bay and Durban. Several smaller detachments operated from George, Mtubatuba and the Eerste River near Cape Town when required.[14] The establishment of dedicated merchant shipping routes along the entire South African coastline further allowed the SAAF and RAF/FAA squadrons to provide adequate air cover to all merchant and naval shipping travelling along these designated routes (see Graph 5.3).567

.jpg)

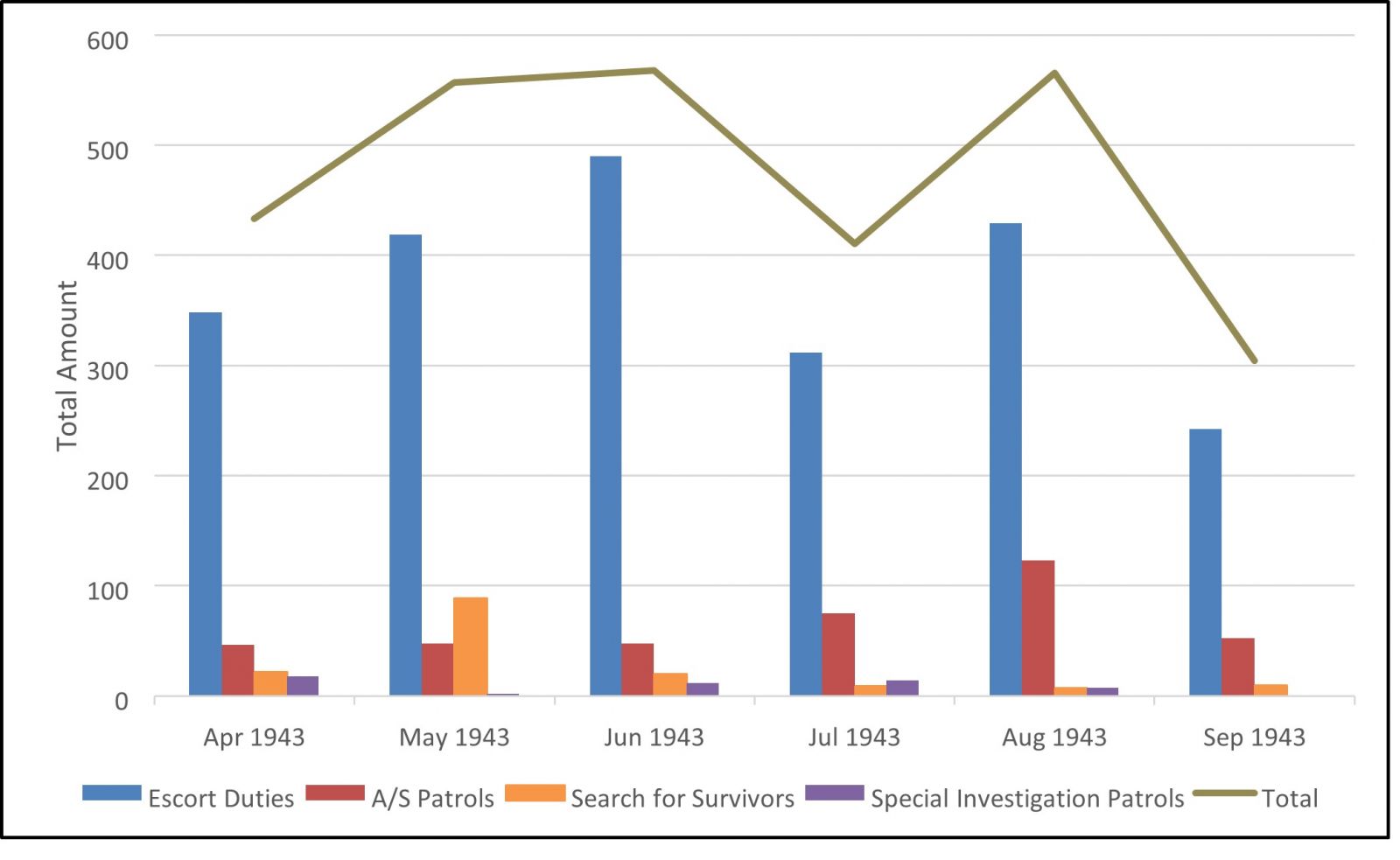

Graph 5.3: Coastal air patrols employed on anti-submarine work and convoy escort duties, 1943568

The need for continuous air cover along the South African coastline in 1943 was ever pressing. Both the SAAF and RAF/FAA realised that in order to meet this need, they required more operational aircraft. By March, Tait and his staff estimated a requirement of at least 24 more Catalinas for operational service in South Africa. They further called for the four SAAF Ventura squadrons in South Africa to be bolstered by an additional two squadrons, which would bring the total number of operational Venturas in the Union up to over a 100.

Secretary of State for Air re Anti-submarine air protection of convoys on the west coast of Africa and the Indian Ocean, 25 Jan 1943.

DOD Archives, CSD, Box 43, File: SANF Anti-submarine Warfare Committees. Minutes of A/S SubCommittee meeting coastal area headquarters, 12 Mar 1943; DOD Archives, CSD, Box 43, File: SANF Anti-submarine Warfare Committees. Report by Officer Commanding HMSAS Gannet re Uboat warfare in the South Atlantic, 10 Jun 1943; DOD Archives, CSD, Box 25, File: SANF Escort Force exercises. Proposed Atlantic convoy instructions re action to counter U-boats anti-asdic tactics.

TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Apr 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, May 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Jun 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Jul 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Aug 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Sept 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Oct 1943

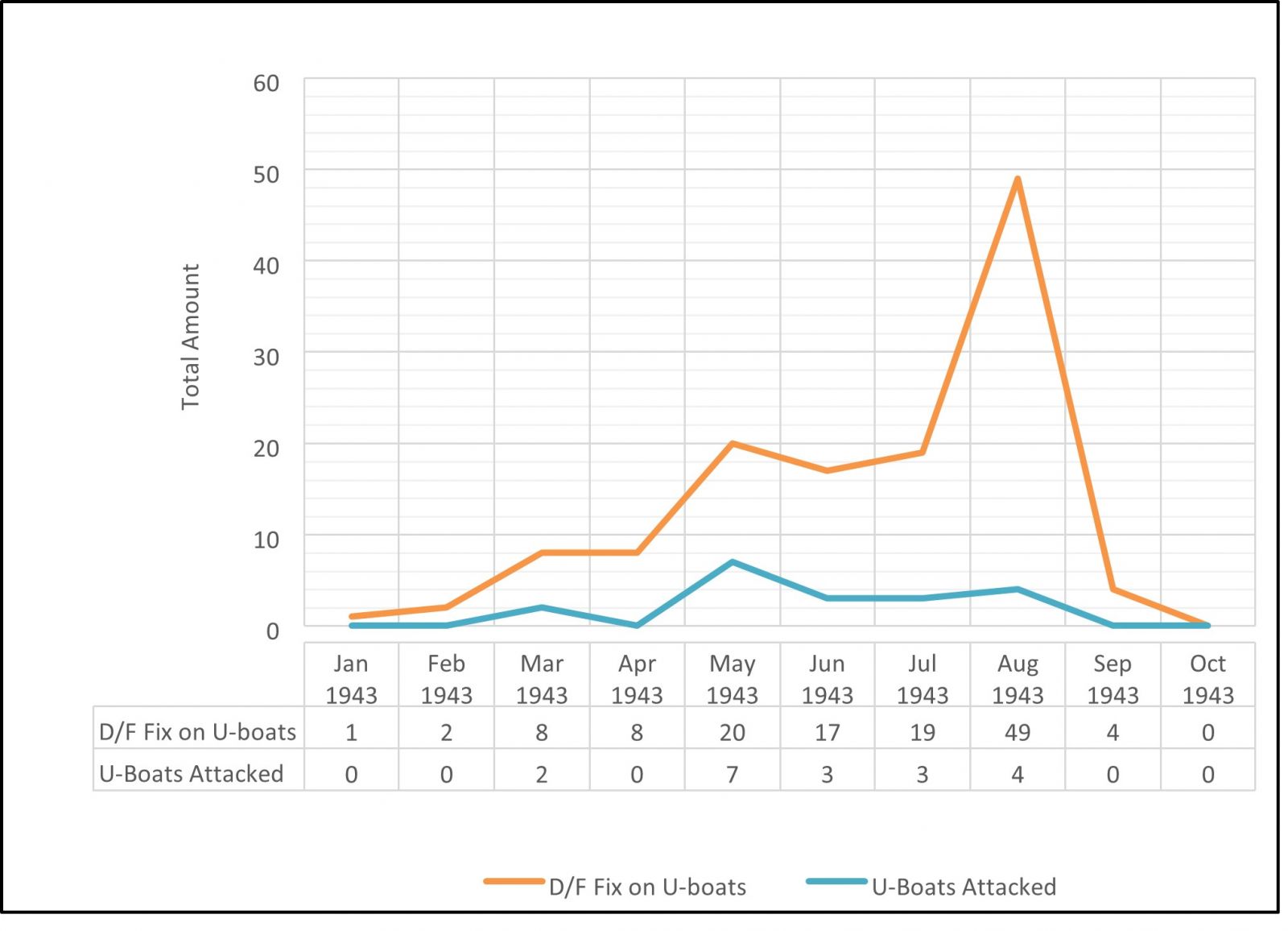

the Combined Headquarters received ample warning from the Admiralty of the presence of U-boats travelling to and from their operational areas off South Africa and further afield. Additionally, throughout 1943, the High-Frequency/Direction Finding (HF/DF) stations belonging to the SO “Y” Organisation in South Africa obtained increasingly accurate plots of the U-boats operational along the Union’s coast through intercepting their wireless transmissions (see Graph 5.5). This naturally allowed Combined Headquarters to allocate and dispatch the appropriate naval and air forces for offensive operations aimed at locating and destroying the U-boats active in South African waters.[23]

|

Required Strength |

Actual Strength |

Deficiency |

|

|||

|

Aircraft |

Squadrons |

Aircraft |

Squadrons |

Aircraft |

Squadrons |

|

|

Catalina |

117 |

13 |

57 |

7 |

60 |

6 |

|

Hudson |

0 |

0 |

32 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Ventura |

62 |

5 |

38 |

3 |

24 |

2 |

|

Wellington |

48 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

47 |

2 |

|

Liberator |

12 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

1 |

|

Total |

239 |

22 |

128 |

13 |

143 |

11 |

Table 5.3: Aircraft requirements in South Africa[15]

In reality, however, the situation was far from adequate. A small number of aircraft had to carry a considerably large operational load during the course of 1943. As a result, there was an operational deficiency of nearly 143 aircraft in South Africa. These were desperately needed in the ASW sphere (see table 5.3). Additionally, the South Atlantic Station regarded the Venturas in service with the SAAF as entirely unsatisfactory for inshore escort work. They also felt that the current South African policy of exchanging Ventura crews between service in the Middle East and off the South African coast was unacceptable. The operational experience gained by SAAF personnel in the Middle East, they argued, had no bearing on the operational conditions encountered off the South African coastline. After Van Ryneveld became aware of the matter, and upon the implementation of remedial action, all SAAF Ventura crews operational in the Union received adequate training in A/S as well as escort work.[16]

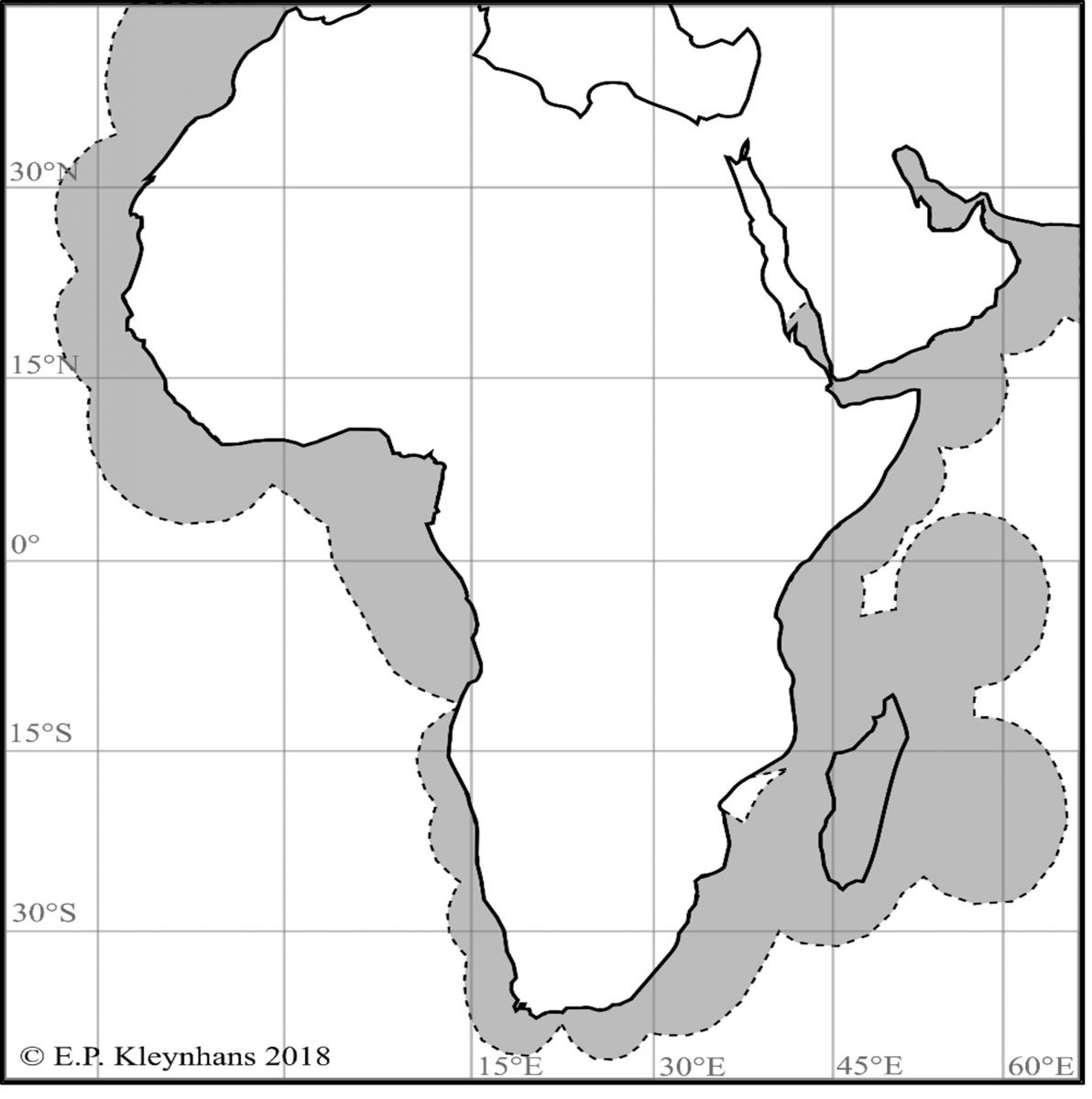

Coastal air patrols, particularly on A/S work and escort duties, remained a regular feature along the South African coast until about October 1943. An investigation of the South Atlantic Station war diaries between April and August 1943 highlights the fact that coastal air patrols – particularly those on escort duties – provided some immunity to merchant shipping from attack by U-boats. In truth, only in a few instances between June and July were escorted convoys with air cover attacked along the South African coast (see Map 5.3). The majority of merchant shipping attacked in South African waters during this period did not travel in convoy, did not have any air cover, and were attacked at night. Tait and his staff argued that these incidents by themselves proved the real value of coastal aerial escorts.[17] From August to October, two occurrences prompted the number of coastal air patrols to decrease exponentially. They were the marked decrease in merchant sinkings along the South African coast, and the apparent withdrawal of U-boats from operations in South African waters (see Graph 5.4).

Map 5.3: Extent of air cover available to convoys along the African coastline, 1943[18]

Graph 5.4: Total number of coastal air patrols off the South African coastline, 1943[19]

There was thus no longer an operational need to provide continuous air cover along the South Africa coast, especially since all convoys in these waters ceased on 16 September. Between April and September, at least 2838 coastal air patrols took place along the South African coast. Their breakdown of sorties was as follows: escort duties – 78.92%; A/S patrols – 13.74%; searches for survivors – 5.53%; and special investigation patrols – 1.79%.[20] The changing operational situation also prompted the British authorities to withdraw all RAF and FAA squadrons in South Africa, except for No. 262 RAF Squadron which continued to be based at Durban with a detachment at Langebaan.[21]

Graph 5.5: Total number of D/F fixes and reported attacks on U-boats, 1943576

Last, the formation of a Combined Operations Room at Combined Headquarters in Cape Town, manned by members of both the UDF and South Atlantic Station, ensured unity of action throughout the planning and execution of ASW measures and operations in South African waters. The operational experience gained by both the South African and Allied air and naval forces throughout 1942 and 1943, furthermore assured that a swift, calculated, decision-making process underpinned the hunt for German U-boats still operational off the South African coast during the remainder of the war.[22] By 1943, the Combined Headquarters received ample warning from the Admiralty of the presence of U-boats travelling to and from their operational areas off South Africa and further afield. Additionally, throughout 1943, the High-Frequency/Direction Finding (HF/DF) stations belonging to the SO “Y” Organisation in South Africa obtained increasingly accurate plots of the U-boats operational along the Union’s coast through intercepting their wireless transmissions (see Graph 5.5). This naturally allowed Combined Headquarters to allocate and dispatch the appropriate naval and air forces for offensive operations aimed at locating and destroying the U-boats active in South African waters.[23]

576TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Jan 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Feb 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Mar 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Apr 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, May 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Jun 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Jul 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Aug 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Sept 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Oct 1943.

Despite the major improvements in ASW measures discussed supra, Tait and Somerville identified several matters relating to ASW that remained problematic. To some extent, these circumstances contributed to the continued loss of merchant shipping to U-boat operations in the Southern Oceans throughout 1943. First, it was argued that the quality and experience of convoy commanders employed in South African waters remained wanting throughout. Unfortunately, the cream of the RN officers regarded service with the South Atlantic Station as a backwater posting, farremoved from the ‘real’ naval war and not conducive to promotion. Tait and Somerville were only too aware that an experienced convoy commander, with adequate A/S vessels and staff under his command, proved crucial when under attack by U-boats.[24]

Second, the continued illumination of some coastal lights, such as the Cape Agulhas lighthouse, helped the U-boats to identify targets, and establish their positions along the South African coastline. A clear example was the sinking of the merchantman Queen Anne (4,937 tons) on 10 February 1943, which had been silhouetted by the illuminated beam coming from the Cape Agulhas lighthouse. After June 1942, only the lighthouses at Cape Point and Cape Agulhas remained fully lit, while the SAR&H ordered the extinguishing of the remaining non-essential coastal lights. All harbour, shore and street lights were also reduced in illumination and screened from seaward. By mid February 1943, however, the remaining coastal lights in operation had been reduced in power and illumination.

By the end of September, Coastal Area Command had reviewed the blackout conditions enforced along the South African coast and drastically altered them. The improved operational conditions prompted Coastal Area Command to alter the blackout conditions greatly, and even suspend the blackouts at Port Elizabeth and East London altogether. By 31 May 1945, all coastal lighting along the South African coastline reverted to its normal peacetime illumination strength.[25]

Third, during some stages, the SAAF and RAF aircraft, which provided cover for the convoys, travelled too far away from the ships they were protecting. As a result, a revised, close-escort programme came into being for aircraft accompanying convoys, whereby circuits of 20, 10 and 5 miles had to be maintained by the aircraft. This allowed for close air support to the convoy, while some of the aircraft conducted long-range reconnaissance ahead and to the flanks of the convoy in the search for U-boats.[26]

Fourth, there were several improvements in shore–ship wireless transmissions, which was facilitated by the greater number of wireless stations available along the South African coast by the latter half of 1943. Despite this, communications between merchant shipping and shore-based establishments in the Union remained wanting. As a result, news of U-boat attacks were trasnmitted too late to activate the appropriate ASW measures.[27] Lastly, several of the convoy escorts operational in South African waters, predominantly South African trawlers, were too slow to conduct efficient A/S sweeps around the convoys, let alone keep up with the convoy itself. Their speed was thus a considerable risk to the protection of the convoys around the South African coast throughout the war.[28]

In July 1943, the Admiralty dispatched Capt D.C. Howard-Johnston RN, an expert who was shaping policy to deal with the new Type XXO high speed U-boats, to South Africa. He was to assist and advise the staff of the South Atlantic Station and Coastal Area Command on the conduct of A/S operations, as well as the control and training of these forces. Howard-Johnston arrived in South Africa on 28 July, and directly reported to the Combined Headquarters in Cape Town. Without delay, he acquainted himself with the state of A/S operations in the South African waters. During the course of his stay, Howard-Johnston visited all RN and SANF vessels employed on escort and A/S duties and each of the RAF and SAAF operational squadrons. He also called on all South African and British shore establishments, fortress commands, operational headquarters and training establishments situated along the South African coast between Simon’s Town and St Lucia. During these visits, he readily discussed current tendencies in A/S operations. He additionally spent a considerable amount of time on talks, lectures and small tactical games for which he utilised the British A/S experience in the Western Approaches as an example. Over and above this, he issued a report to the Admiralty on his visit. The assessment included an evaluation of the South Atlantic Station from an A/S point of view – particularly at the strategic, operational and tactical levels of war.[29]

At the strategic level, Howard-Johnston was concerned that the Combined Headquarters in Cape Town controlled all convoys and A/S operations. The centralisation of control particularly perturbed him. He compared the control of operations at sea in the Mozambique Channel from Cape Town to that of the command over similar operations between Gibraltar and Sardinia from Plymouth. He argued that Durban was, in effect, the true operational centre along the South African coast.

The reinforcement of the South Atlantic Station by modern A/S vessels was recommended, along with the improved quality of air cover available across southern Africa. According to Howard-Johnston, both of the above, along with the wireless interceptions from the HF/DF stations, opened up the possibility of dedicated offensive operations aimed at the destruction of U-boats. At the operational level, Howard Johnston was particularly impressed with the SO “Y” Organisation in South Africa. He commended the tireless efforts of the HF/DF stations in locating U-boats operational along the coast. Throughout August, the South Atlantic Station also experimented in fitting various RN vessels with HF/DF equipment. This greatly increased their offensive possibilities when working in conjunction with the shore-based HF/DF stations. During the month of his stay, three RN frigates, generally larger, faster and more seaworthy than corvettes, arrived at the South Atlantic Station. The HMS Kale, HMS Tay and HMS Derg were each fitted with the latest experimental HF/DF gear.

Howard-Johnston further stated that a series of combined operations had been instituted off the South African coast. During these operations, both aircraft and naval vessels had conducted sweeps of areas where U-boats would likely operate. While he was at Cape Town, two such operations occurred: Operation KITBAG and Operation HAVERSACK. Howard-Johnston deduced that the observed reduction in seaborne traffic in South African waters had opened up the ability of regular offensive action by air and surface forces without depriving merchant shipping of the nominal forces required for escorting convoys.[30]

Howard-Johnston did not spare the South Atlantic Station on his criticism of the alarming state of affairs prevalent at a tactical level. His principle concern was that the surface escorts, particularly the SANF vessels, lacked adroitness when a U-boat attack on a convoy commenced. Moreover, he was alarmed at the slow speed of these vessels, as well as the outdated nature of their A/S equipment. Leaving no doubt as to his opinion, he argued that there was no appropriate strategic policy with regard to ASW, and that the rudimentary tactical policy in place was largely based on the Atlantic Convoy Instructions of 1943. It was thus a policy altogether unsuited for South African waters and its unique operational conditions.

Howard-Johnston was particularly alarmed that this state of affairs continued to exist after the three years of naval war, and two separate U-boat offensives off the South African coast. He pointed out the need for the appointment of an A/S Officer on the staff of the South Atlantic Station to coordinate all A/S work, as well as regular visits by officers with practical A/S experience to help with training and operations.

Under Howard-Johnston’s watch, a tactical policy applicable to local operational circumstances was drawn up. In brief, the tactical policy focussed on avoiding attacks by U-boats as far as possible through appropriate A/S measures. At the same time, the surface and air units would be informed of the appropriate offensive actions to take in the event of an attack on a U-boat. Howard-Johnston was satisfied that most of the recommendations which he made to Tait and his staff were well received, and subsequently put into action in South African waters. One of the immediate results of the improvements in ASW during the latter half of 1943 stands out. It is the location and destruction of U-197 towards the end of August, which coincided with Howard- Johnston’s visit to the Union.[31]

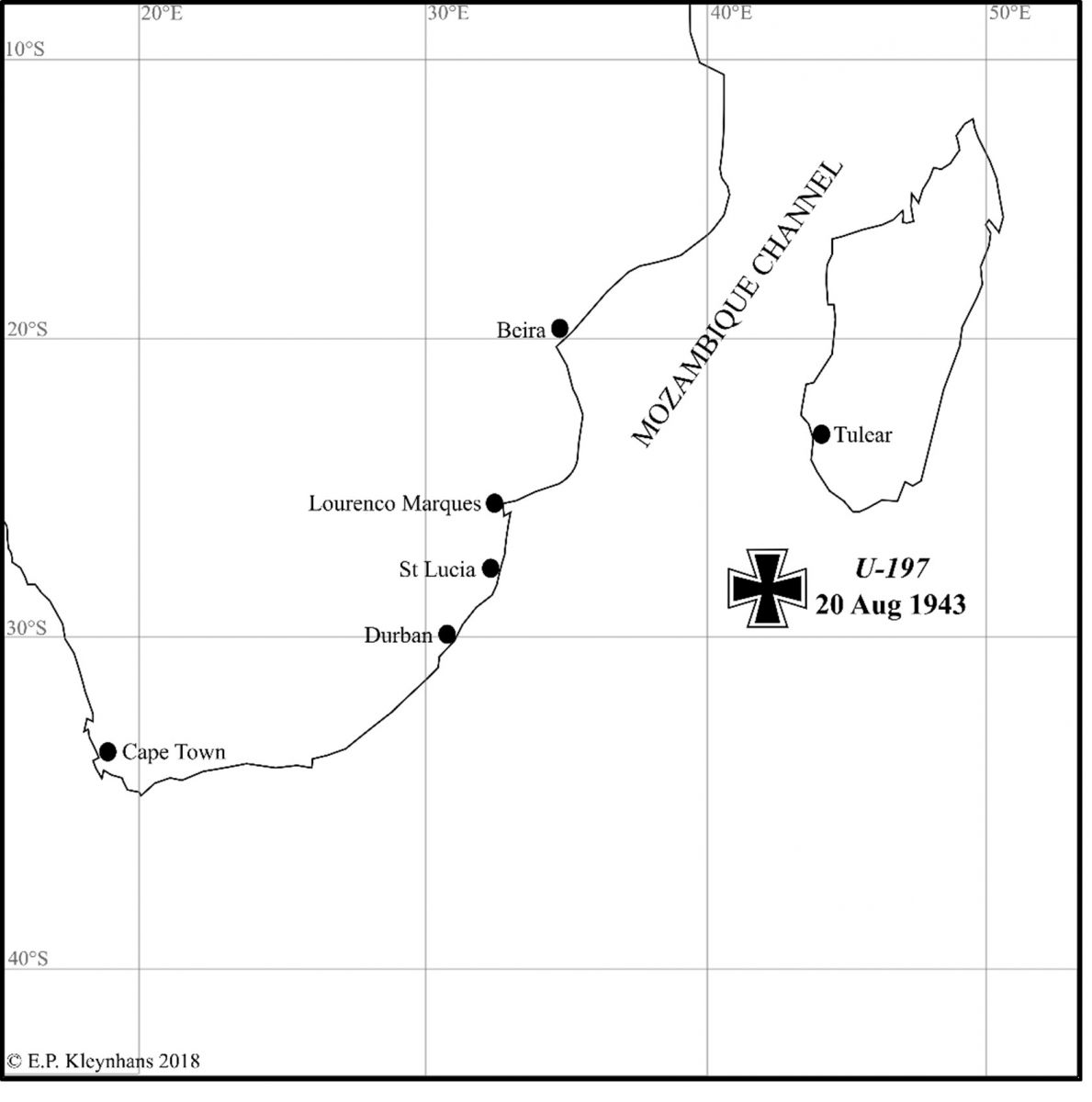

Between 16 and 18 August 1943, a number of HF/DF stations in South Africa picked up several wireless transmissions sent between the BdU, U-181 (Lüth), U-197 (Bartels) and U-196 (Kentrat). The sole purpose of these indiscriminate wireless transmissions was to arrange a routine rendezvous between the three U-boats for the exchange of a new secret cypher called ‘Bellatrix’, as well as for further operational instructions. On 19 August, U-181 met U-197 in an area approximately 100 miles to the south of Cape St Marie in Madagascar. Lüth subsequently took it upon himself to meet up with Kentrat 280 miles south-west of his current position. The two U-boats met the following day, during which they picked up a wireless transmission from Bartels stating that an aircraft had attacked him. It was the Combined Headquarters in Cape Town which had utilised the former wireless interceptions to accurately pinpoint the position of U-197 in the southern extremity of the Mozambican channel. The location of the Uboat was fixed to an operational area approximately 250 miles south-west of Cape St Marie in Madagascar. Catalinas from No. 259 RAF Squadron in St Lucia were ordered to work at the limits of their endurance by joining the search for the U-boat. The aircraft subsequently rebased to Tulear in south-western Madagascar, which they continued to use as a forward operating base throughout the operation.[32]

Fig 5.6: Robert Bartels – the commander of U-197[33]

Shortly after midday on 20 August, Catalina C/259, piloted by Flt Lt O. Barnett, sighted U-197. The U-Boat had surfaced approximately 300 miles to the south-west of Cape St Marie. Barnett immediately launched an attack and succeeded in dropping at least six depth-charges on U-197. An unequivocal reply came from the U-boat in the form of machinegun and canon fire throughout the attack, though the Catalina received no damage. Barnett realised the success of his attack as the U-boat critically listed to port while leaking a substantial amount of diesel oil.[34] The U-boat submerged for a brief while in the afternoon, whereafter it surfaced and once more tried to engage the Catalina. In the meanwhile, Barnett had dropped smoke- and flare-floats, while awaiting the arrival of more aircraft from St Lucia. Throughout the afternoon Barnett continued to circle U-197, keeping constant visual contact with the stricken U-boat. Later in the afternoon, shortly before dark, Catalina N/265, piloted by Flt Off C.E. Robin, joined Barnett and commenced a final onslaught on U-197. During this final attack, Robin made three runs during which six depth-charges managed to find their targets successfully. This final attack proved fatal, and Bartels and his U-boat disappeared below the surface for one last time, leaving only a large patch of diesel oil behind to confirm the successful kill (see Map 5.4).[35]

Map 5.4: Location of the sinking of U-197

While the sinking of U-197 proved the first sole air success during the course of the naval war in the Southern Oceans,[36] it also highlighted the great strides made regarding ASW in these waters. The ASW measures in force by August 1943 certainly stand in stark contrast to those implemented during October 1942. The establishment of convoys, the provision of adequate air and naval escorts, as well near continuous A/S and coastal air patrols along the South African coastline, had effectively robbed the Uboats of their initial operational advantage. This is evident through the near monthly reduction in the number of merchant sinkings in South African waters. While the Uboats still scored some operational successes, these were few and far between. More importantly, however, the UDF and South Atlantic Station had succeeded in securing control over the operational initiative in the Southern Oceans. This control was mainly imposed through the increasing interception and pinpointing of U-boat positions by the HF/DF stations in the Union. The sinking of U-197 also ushered in an entirely new phase in the naval war, one where the UDF and South Atlantic Station moved over to the offensive and instituted a number of combined operations aimed at the destruction of U-boats.

[1] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-Boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters.

[2] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 220, File: Union War Histories Translations 14a. U-boat Operations of the Axis Powers in S.A. Waters compiled by Dr Jurgen Rohwer, 1954.

[3] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945.

[4] Roskill, The War at Sea: Volume III – The Offensive (Part II), p. 86.

[5] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon Cumming U-boat material. The Commanders-in-Chief South Atlantic and Eastern Fleet, Report on the safety of shipping in South African waters, 30

[6] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon Cumming U-boat material. The Commanders-inChief South Atlantic and Eastern Fleet, Report on the safety of shipping in South African waters, 30 Mar 1943.

[7] DOD Archives, CSD, Box 15, File: Group sailing operations Union waters. Note on commencement and ceasing of group sailings, 1944; DOD Archives, CSD, Box 15, File: Policy (escort groups). Note on commencement and ceasing of group sailings, 1944; DOD Archives, CSD, Box 43, File: SANF Anti-submarine Warfare Committees. Minutes of A/S Sub-Committee meeting coastal area headquarters, 12 Mar 1943.

[8] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon Cumming U-boat material. The Commanders-inChief South Atlantic and Eastern Fleet, Report on the safety of shipping in South African waters, 30 Mar 1943.

[9] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon Cumming U-boat material. The Commanders-in-

Chief South Atlantic and Eastern Fleet, Report on the safety of shipping in South African waters, 30

[10] DOD Archives, CSD, Box 15, File: Policy (escort groups). CSD Approval of exchange with RN of A/S vessels, 15 Nov 1943; DOD Archives, CSD, Box 15, File: Policy (escort groups). Personal correspondence between CSD and GOC coastal area re SANF vessels and A/S warfare, 30 Oct 1942; DOD Archives, CSD, Box 15, File: Policy (escort groups). Correspondence between CSD and SANOi/c Durban re SANF A/S vessels on escort duties, 28 Apr 1943; DOD Archives, CSD, Box 15, File: Policy (escort groups). Correspondence between CSD and SANOi/c Durban re participation of SANF vessels in convoy escorts from SA ports, 23 Jan 1943.

[11] TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Mar 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Apr 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, May 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Jun 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Jul 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Aug 1943.

[12] TNA, ADM 1/12643, Anti-Submarine Operations – South Atlantic Station. Report of Captain Howard-Johnston’s Visit to the Cape, Oct 1943.

[13] DOD Archives, Photographic Repository. 841000346 - RAF Catalina of 262 Sqn.

[14] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon Cumming U-boat material. The Commanders-in-Chief South Atlantic and Eastern Fleet, Report on the safety of shipping in South African waters, 30; TNA, AIR 9/190, Anti U-boat Warfare – African Shipping. Memorandum by the [15] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon Cumming U-boat material. The Commanders-inChief South Atlantic and Eastern Fleet, Report on the safety of shipping in South African waters, 30 Mar 1943.

[16] TNA, AIR 9/190, Anti U-boat Warfare – African Shipping. Memorandum by the Secretary of State for Air re Anti-submarine air protection of convoys on the west coast of Africa and the Indian Ocean, 25 Jan 1943; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon Cumming U-boat material. The Commanders-in-Chief South Atlantic and Eastern Fleet, Report on the safety of shipping in South African waters, 30 Mar 1943.

[17] TNA, AIR 9/190, Anti U-boat Warfare – African Shipping. Anti-U-boat protection in the Cape Area, 9 Jun 1943; DOD Archives, CSD, Box 43, File: SANF Anti-Submarine Warfare Committees. U-boat Warfare in the South Atlantic – Analysis of Attack by U-boat, 10 Jun 1943.

[18] TNA, AIR 9/190, Anti U-boat Warfare – African Shipping. Memorandum by the Secretary of State for Air re Anti-submarine air protection of convoys on the west coast of Africa and the Indian Ocean, 25 Jan 1943. Map drawn by the author, from information contained in the afore-mentioned document.

[19] TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Apr 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, May 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Jun 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Jul 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Aug 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Sept 1943.

[20] TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Apr 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, May 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Jun 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Jul 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Aug 1943; TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Sept 1943.

[21] TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Oct 1943.

[22] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon Cumming U-boat material. The Commander-inChief South Atlantic and eastern fleet, Report on the safety of shipping in South African water, 30 March 1943; DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 123, File: Coast 22 (O) Organisation general. Letter from air headquarters East Africa to OC Advanced Operations Section air headquarters East Africa re operation control to be exercised by the Advanced Operations Section, air headquarters, East Africa, situated at Cape Town, 11 May 1943.

[23] DOD Archives, CGS War, Box 265, File: Sitreps coastal area. Most secret cypher between Coastcom and Dechief Fortcoms, 21 Aug 1943.

[24] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon Cumming U-boat material. The Commanders-inChief South Atlantic and Eastern Fleet, Report on the safety of shipping in South African waters, 30 Mar 1943.

[25] DOD Archives, CGS War, Box 38, File: Blackouts and lighthouses. Harbour and Coast Lights, 19 Jun 1942; DOD Archives, CGS War, Box 38, File: Blackouts and lighthouses. Correspondence between Secretary of Defence and Minister of Justice re black-out conditions coastal area, 29 Sept 1943; DOD Archives, CGS War, Box 38, File: Blackouts and lighthouses. Letter from C-in-C South Atlantic to CGS, 31 May 1945.

[26] DOD Archives, CFAD, Box 12, File: Cape Fortress Intelligence Summary. Cape Fortress intelligence summary no. 10, 4 Dec 1942 (Appendix A – Anti-submarine warfare); DOD Archives, CFAD, Box 12, File: Intelligence – Attacks on U-boats and submarines. Lecture on A/S warfare by Wing Commander Lombard, 22 Feb 1943.

[27] DOD Archives, CGS War, Box 226, File: W.T. stations: Ship to shore & ship to aircraft. Letter from Harlech to Smuts re Admiralty Policy with regard to wireless communication, 9 Mar 1943.

[28] DOD Archives, CSD, Box 25, File: SANF Escort Force exercises. Proposed Atlantic convoy instructions re action to counter U-boats anti-asdic tactics; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon Cumming U-boat material. The Commanders-in-Chief South Atlantic and Eastern Fleet, Report on the safety of shipping in South African waters, 30 Mar 1943; DOD Archives, CGS War, Box226, File: Wireless stations (communications with). Secret note on the interception of illicit communications, 2 Nov 1939.

[29] TNA, ADM 1/12643, Anti-Submarine Operations – South Atlantic Station. Report of Captain Howard-Johnston’s Visit to the Cape, Oct 1943. For more on the critical contribution of HowardJohnston in terms of anti-submarine warfare see Llewellyn-Jones, The Royal Navy and AntiSubmarine Warfare, 1917-49.

[30] TNA, ADM 1/12643, Anti-Submarine Operations – South Atlantic Station. Report of Captain Howard-Johnston’s Visit to the Cape, Oct 1943.

[31] TNA, ADM 1/12643, Anti-Submarine Operations – South Atlantic Station. Report of Captain Howard-Johnston’s Visit to the Cape, Oct 1943.

[32] Turner et al. War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 234-235.

[33] https://uboat.net/men/commanders/43.html (Accessed 6 May 2018).

[34] TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Aug 1943.

[35] Turner et al. War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 235–236.

[36] TNA, ADM 199/2334. South Atlantic War Diary, January to October 1943. South Atlantic War Diary, Aug 1943.