THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

31)ASW OFF SOUTH AFRICA 1942 44

Anti Submarine War off Southern Africa 1942 - 1944

It was the commencement of the first sustained German U-boat operation in October 1942 that awakened the need for dedicated anti-submarine warfare (ASW) measures in South African waters. Before this, the full effect of the naval war was rather distant. The unreality of war resulted in an undeniable indifference regarding the adoption of ASW measures.

The resultant U-boat offensives off the southern African coast between October 1942 and August 1943, compelled the South African and British naval authorities to adopt a series of ASW measures. These steps were aimed at reducing the number of merchant sinkings in the waters off South Africa. The ASW measures implemented after October 1942 resulted in a notable decrease in the number of merchants sunk along the South African coast from 1943 onwards. Moreover, three German U-boats were sunk between 1942 and 1944. These sinkings provided another tangible measure of the success of the ASW measures in place along the South African coast from October 1942.

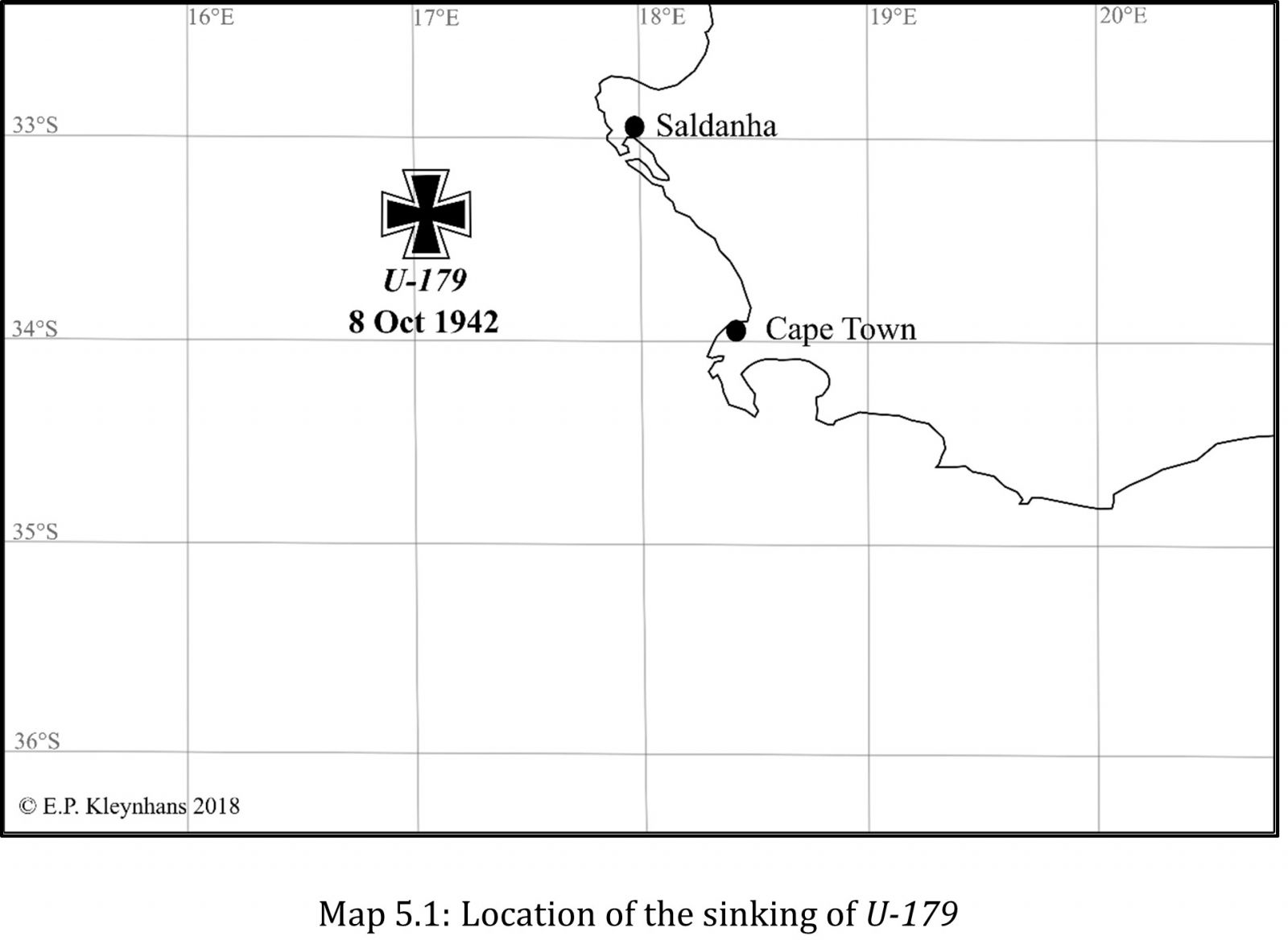

The two objectives of this final chapter are wide ranging. In the first place, the evolution of the ASW in South African waters is scrutinised. This is done through the comparison of the ASW measures in place before the commencement of the main U-boat offensive in October 1942, with those prevalent during 1944 when the U-boat offensives in said waters ceased all-together. Secondly, the effectiveness of the ASW measures off the South African coast will be evaluated. Apart from the obvious diminishing merchant losses, the sinkings of the three German submarines in 1942 (U-179), 1943 (U-197) and 1944 (UIT-22) will be discussed. These U-boats were arguably sunk at the beginning, the height, and at the end of the German submarine offensives in South African waters. They thus reflect positively on the improvements made apropos ASW in these waters throughout the period concerned.

5.1 Lacklustre attitudes, the start of the U-boat offensives, and a chance sinking

The Eisbär group commenced their attack on the shipping off Cape Town on 7 October 1942. Among them were U-68 (Merten), U-172 (Emmermann), U-504 (Poske) and U-159 (Witte). Before launching the submarine offensive, the B-Dienst estimated Cape Town harbour to contain up to 50 anchored ships at any given time. Furthermore, the Befehlshaber der U-Boote (BdU) believed that a surprise attack by the Eisbär boats on shipping in the Cape Town harbour could achieve significant sinking results, owing to the element of surprise. Surprisingly, both the U-boat commanders and the BdU were of the opinion that the South African defences were unprepared for a sudden onslaught on merchant shipping in the waters off Cape Town. This was most likely because it seemed to them that neither their wireless transmissions nor their presence was detected while travelling south.[1]

In the days preceding the launching of the surprise attacks, U-68 and U-172 conducted several brazen reconnaissance sorties into Table Bay and the approaches to Cape Town harbour. During these forays, the two U-boat commanders were soon able to gauge both the extent and the state of readiness of the South African coastal defences.[2]

Carl Emmermann’s account of the evident unpreparedness off Cape Town is enlightening:

The picture which the town and harbour presented was so beautiful and so peaceful that we stayed a few hours on the surface and called up the crew one by one to the bridge to enjoy the sight. Cape Town at that moment was busy with an air-raid exercise. There were a few target planes circling above the brilliantly illuminated city, and the long groping fingers of the searchlights tried to catch them in their beams. The picture reminded us of the scenes in our German towns at the beginning of the war: everything indicated that here people felt they were remote from hostilities … Brilliant sunshine on the roadstead, the sea as smooth as a mirror, only a strong swell making it difficult to keep the U-boat at a steady depth. We were only a few hundred metres from the main shipping channel, ships were passing close by and quite unaware of the nearness of the enemy. Quite undisturbed, we were able to take bearings of the entrance and exit channels and study the harbour installations.[3]

Unbeknown to the BdU, U-172 launched surprise attacks on two unsuspecting merchantmen on the morning of 7 October. These strikes resulted in the sinking of the Chikasaw City (6,196 tons) and the Firethorn (4,700 tons). The sinkings, however, went unnoticed, as neither the Chikasaw City nor Firethorn managed to transmit distress signals prior to their sinkings. The Combined Headquarters in Cape Town were only informed of these sinkings after their survivors were picked up the following afternoon and evening.[4] For the remainder of the day, the U-boats refrained from attacking any more merchants. After receiving the order to attack that night, the U-boats managed to sink the Boringia (5,821 tons), Koumoundouros (3,598 tons), Gaasterkerk (8,679 tons), and Clan Mactavish (7,631 tons). By daybreak on 8 October, the Eisbär boats could account for nearly 33,000 tons of shipping sunk off Cape Town. The success of the surprise attacks was, however, short-lived. The South African coastal defences were in fact not entirely unprepared for the sudden onslaught on the merchant shipping off its coastline.[5]

During the early hours of 8 October, the South African and Allied authorities activated all ASW measures. These followed the receipt of several reports of explosions and light flashes near the Cape Point lighthouse. A single Ventura from No. 23 Torpedo Bomber Reconnaissance (TBR) South African Air Force (SAAF) Squadron was dispatched to investigate these reports. Shortly after daybreak, the aircraft sighted the wreckage of the Gaasterkerk 20 miles south-west of Cape Point. Four lifeboats with some survivors were also identified. Soon after that, the South Atlantic Station dispatched a corvette, HMS Rockrose, and two destroyers, HMAS Nizam and HMS Foxhound. They were sent to a general area off Cape Point to assist in the rescue of survivors, as the sinkings of Boringia and Clan Mactavish had also became known. The U-boat attacks during that morning were rather brazen as they operated on the surface, but increasing aerial patrols forced them to remain submerged. Throughout the morning, the Venturas from No. 23 SAAF TBR Squadron maintained a continuous patrol off Cape Point and assisted in pinpointing the location of survivors adrift in lifeboats.[6]

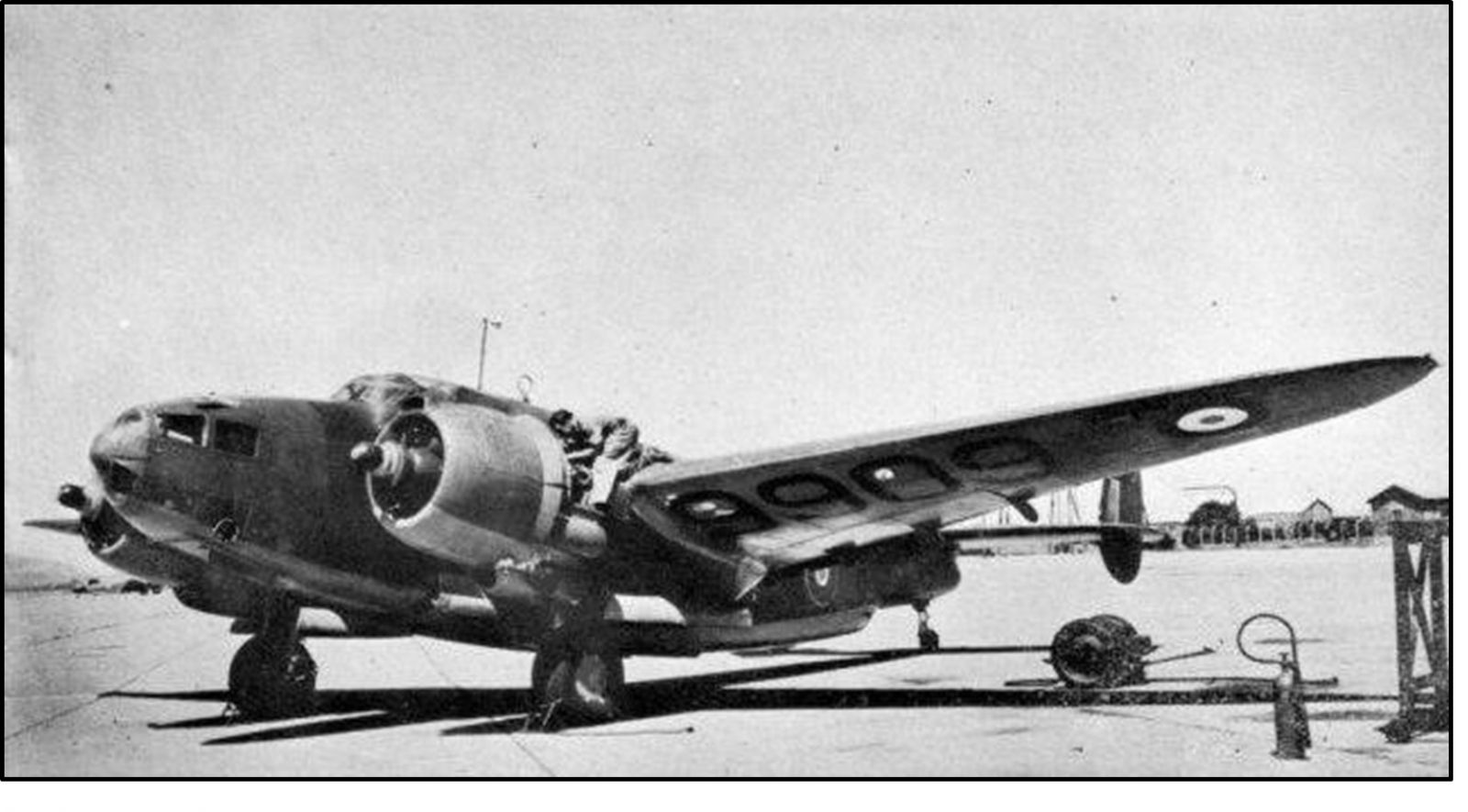

Fig 5.1: A Ventura in service with the SAAF during the war[7]

During the course of the morning’s air patrols, there were two separate instances during which South African aircraft succesfully engaged U-boats in the waters off Cape Town. After a U-boat was spotted 130 miles to the west of Cape Town, a Ventura engaged it and dropped four 250 lb depth charges in its vicinity after it submerged. This attack received a stern rebuff from the Commander Coastal Air Defences, who regarded it a waste of bombs. The second attack occurred soon after midday when a Ventura observed a U-boat at periscope depth some miles off Green Point. Due to a communications breakdown within the Ventura – partly caused by the transmission of an outgoing signal – there was a considerable delay before releasing the four 250 lb depth-charges in the vicinity of the U-boat. It is of interest to note that none of the four U-boats operational in the area reported being attacked by aircraft on 8 October. During the remainder of the afternoon, the Venturas from No. 23 TBR SAAF Squadron flew several more reconnaissance sorties in the hope of spotting more survivors and locating the U-boats. They were assisted by three Albacores from the Royal Navy (RN) Fleet Air Arm (FAA), deployed to South Africa to help bolster its coastal defences and for convoy escort duties.[8]

Two RN destroyers, HMS Active and HMS Arrow, sailed shortly before midday from Simon’s Town to assist in locating and picking up survivors from the Clan Mactavish. All South African Naval Forces (SANF) anti-submarine (A/S) vessels were, however, retained to keep constant control of the perimeter of the Cape Town anchorage. The exception was HMSAS Vereeniging, which accompanied the Mine Clearance Flotilla while they once more swept the area near Cape Point which the Doggerbank had mined that April. During the course of the day, the Union Defence Force (UDF) and South Atlantic Station issued several pertinent ASW orders due to the intensifying U-boat operations off Cape Town. To start with, the use of all coastal and harbour navigation lights, radio beacons and fog signals were discontinued with immediate effect. While the use of Saldanha harbour since June reduced the daily number of ships in Table Bay to an average of twenty, a system of double-banking provided ten extra berths within the Cape Town harbour that day. This considerably reduced the number of merchants lying in the undefended roadstead. Moreover, some of the sailings planned for the following days were postponed. A wireless message was also sent to all shipping in South African waters. They were told not to approach within seventy miles of Cape Town during the hours of darkness.527

That night, all the Venturas from No. 23 TBR SAAF Squadron were grounded, as they lacked the required equipment for night operations. The RN vessels operational off Cape Town, however, had a very busy night hunting the U-boats and looking for survivors. During the night of 8/9 October U-68 managed to sink a further four merchants, the Sarthe (5,271 tons), Swiftsure (8,206 tons), Examelia (4,981 tons) and Belgian Fighter (5,403 tons). The other U-boats had a less successful evening, as the hunters appeared to become the hunted.

During that night Emmermann once more navigated his U-boat to the approaches of Table Bay with the hope of scoring another surprise attack. As soon as the U-boat entered the approaches, Emmermann heard distinct propeller noises which signalled an impending attack. HMS Rockrose attacked U-172 in an area approximately 70 miles to the west of Hout Bay. While HMS Rockrose did not manage to sink U-172 during the night, it did force Emmermann to remain submerged for an extended time. This meant that the U-boat could not recharge its batteries, nor sufficiently ventilate the boat, before daylight.[9] Emmermann’s logbook provides a vivid account of HMS Rockrose’s attack during the night:

2020 – Asdic impulses can be heard on my set… am creeping along.

2037 – 12 depth-charges, ineffectively released. Slight damage, chiefly to fuses. Gyrocompass failing. Lid on tube IV not tight. Shortly after, two further patterns of 12 each, farther away.

2100 – Two U-boat chasers clearly audible, alternately on my course, trying to locate me.

0100 – U-boat chasers continue near my boat. They operate very skilfully, in spite of my constant doubling here and there.

0500 – No longer possible to surface while it is dark. Conditions for listening and locating are ideal, as the sea is smooth. Every little noise made in the boat produces reaction.[10]

On the same night, the destroyers HMAS Nizam, HMS Foxhound and HMS Active were operational approximately 60 miles to the west of Dassen Island travelling on a course roughly South by East. Initially, the vessels were dispatched to help collect survivors from the City of Athens (6,558 tons). Shortly before midnight, however, HMS Active – under the command of Lt Cdr Michael Tomkinson – obtained a radar contact on a bearing of 150° at a distance of 2,500 yards.[11] Unbeknown to the Eisbär group, U-179 (Sobe) had sailed from the equator at such a high speed, that he had arrived in the waters off Cape Town in time for the unexpected attacks. After successfully sinking the Pantelis (3,845 tons) on 8 October, U-179 was caught off guard and sunk by HMS Active on the same night (see Map 5.1).[12] In an extract from the Proceedings of the U-Boat Assessment Committee, there is an unmatched account of the attack and sinking of U179. The report states:

Shortly after, an asdic contact right ahead at a range of 1,600 yards was obtained and a large U-boat sighted on the surface, inclination 20° [to the] right.

The U-boat appeared to be stopped, presumably charging her batteries. Speed was increased to 25 knots and course altered slightly to starboard to bring [the] U-boat broader on the beam. At 800 yards the target was illuminated by searchlight, and fire was opened by B gun, no hits however being scored. The U-boat dived when range was 500 yards.

[HMS] Active altered towards and steadied on a course about 5° ahead of [the] U-boat’s conning tower. The U-boat passed down the port side at close range on a converging course and was attacked with a 10-charge pattern by eye, set to 50 and 150 feet. The charges are reported to have burst all around the U-boat, the swirl and bubbles caused by its diving still being clearly visible. The depth-charge party reported that the U-boat was blown to the surface as a result of the attack and then disappeared, but this cannot be confirmed. No contact was obtained in spite of a search carried out throughout the night. A large patch of diesel oil came to the surface which, by dawn, was some 3 miles in length and half a mile wide. No wreckage was found.[13]

A post-war report from Emmermann confirms the loss of U-179. The BdU did not realise that U-179 was lost in the waters off Cape Town, and for some time believed that it was sunk near Ascension Island on its return voyage. Emmermann wrote:

During this chase we clearly heard the sounds of another U-boat being sunk. After a bad depth-charge volley, we were able to pick up the sound of sinking quite clearly. On my return, I voiced my opinion that it may have been U-179 (Sobe). Apparently U-179, quite unaware, had slap-bang run right into the first furious wave of defensive actions taken by the enemy and thus sealed her doom.[1]

While the U-boat pickings were initially easy off Cape Town, the surprise gained during the initial attacks started to dwindle by 10 October. The immediate activation of the combined South African and Allied ASW measures ensured that the full extent of the surprise attack in the waters off Cape Town did not materialise. As a result, there was no indiscriminate massacre of anchored shipping as predicted by the BdU. The U-boats had a staggering success by sinking 14 merchantmen (100,902 tons) in a mere four days. Despite this, Donitz ordered the Eisbär group to extend their operational areas to the waters off Port Elizabeth and Durban.[16] His decision was as a direct result of the ASW measures encountered from 8 October onwards. These measures negated the operational advantage gained by the initial surprise attacks, which equally revealed several cracks in the South African coastal defences. In truth, before the commencement of the first sustained U-boat offensive in October, the ASW measures employed in South African waters were somewhat haphazard. They were also embryonic in nature, and curtailed by several factors which warrant further discussion.

First, there was some prior warning of a possible move of a group of German Uboats into the South Atlantic by the end of August. The Headquarters of the South Atlantic Station, however, remained unsure of the exact time and area in which to expect an attack on merchant shipping. Throughout September, the Submarine Tracking Room at Whitehall continued to warn the Combined Headquarters in Cape Town of the southward movement of a group of U-boats through continued wireless interceptions.[17] The sinking of the British troopship Laconia (19,965 tons) on 12 September near Ascension Island, also served to confirm the presence of a group of Uboats travelling southward. While Combined Headquarters in Cape Town thus knew of the impeding U-boat attack in the Southern Oceans, there were insufficient SANF and RN A/S vessels in South Africa to justify pre-emptive offensive patrols.[18]

Any pre-emptive action by the British or South African authorities, moreover, would have alerted German agents in Cape Town that the Allies were aware of the impending attack. This naturally created a somewhat tense situation at Combined Headquarters. Whereas the defence planners continued to expect an attack on merchant shipping off Cape Town from the end of September onwards, the ASW measures in South African waters remained inactive until the U-boat attack commenced. The fact that the sinkings of the Chikasaw City and Firethorn initially went unnoticed, highlighted the point that both the South African and British authorities only became aware of the presence of the Eisbär group by 8 October, and only after a report of the first sinkings. This obliviousness is, however, not unexpected, considering Tait and his staff’s stance. Their conviction was “that the first news of the presence of enemy raiders, whether surface or submarine, in the area will be the report of their first attack.”[19]

Second, because the Axis threat to Allied shipping off the South African coast had not materialised by mid-1942, an apathetic attitude was prevalent in the Union regarding coastal defence. The fact that the Department of Railways and Harbours (SAR&H) only switched off the non-essential harbour and coastal lights during that June – after the commencement of the Japanese submarine offensive in Mozambican waters – highlights the dismal state of affairs.[20] By 4 October, an intelligence appreciation from the South Atlantic Station had failed to report the presence of the U-boats moving south towards Cape Town. This was only days before the Eisbär group launched their surprise attack. It would seem as if Tait and his staff were also lulled into a false sense of security. The feeling of confidence in their safety prevailed despite the various naval intelligence sources indicating the southward movement of a number of U-boats in the Atlantic Ocean since the end of August.540 The focus of the South African and British naval authorities was, instead, on the Indian Ocean, and the presumed threat posed by a further Imperial Japanese Navy operation in these waters.541

Third, the intelligence appreciation furthermore advised that there was an insufficient number of naval forces in South African waters. The consideration of launching an offensive operation in the case of a U-boat attack on merchant shipping was therefore dismissed. Incidentally, the intelligence appreciation acknowledged that the only defence against possible attacks against the trade routes off Cape Town was to either adopt a policy of escorting group sailings and convoys or to enforce a system of evasive routing. The crux of the matter was, however, that without an adequate number of naval vessels available in South African waters, these intended measures were impossible to execute.542

By October, the South Atlantic Station could account for only one dedicated A/S vessel, the Flower-class corvette HMS Rockrose. By good fortune, two destroyers from the Eastern Fleet, HMAS Nizam and HMS Foxhound, were also in Simon’s Town for refit. The arrival of two further destroyers, HMS Arrow and HMS Active, which called at Simon’s Town on their way to Freetown, also bolstered the meagre naval forces. From 8 October, these five vessels operated continuously against the Eisbär group to locate and destroy the U-boats, while also assisting in picking up survivors from the merchant sinkings. The arrival of three vessels drastically strengthened the naval forces operational off Cape Town. They were a Free French corvette, the Commandant Detroyat, on 10 October, and two more RN destroyers that arrived the following day:

HMS Thyme and HMS Cyclamen. By the end of the month, the Commander-in-Chief (C-inC) Eastern Fleet, VAdm (Sir) James Somerville, dispatched a further six destroyers, along with four corvettes and an A/S whaler, for service with the South Atlantic Station. Throughout this period, SANF vessels mainly assisted in the defence of the South African harbours, and in specific instances helped to collect survivors along the coast. The sheer size of the operational area off the South African coast created a situation unfavourable to the productive employment of naval vessels in the pursuit of ASW and Blackouts and lighthouses. Circular from Office of the C-in-C South Atlantic Station (Tait) to Naval Liaison Officers at Durban, East London, Port Elizabeth and Cape Town re harbour and coast lights, 19 Jun 1942.

- DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 127, File: Appreciations navy. C-in-C South Atlantic appreciation of the naval situation in the Cape area, 4 Oct 1942.

- DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 126, File: Coastal appreciations general. A Japanese attack on South Africa: An appreciation from the enemy point of view, 29 Sept 1942.

- DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 127, File: Appreciations navy. C-in-C South Atlantic appreciation of the naval situation in the Cape area, 4 Oct 1942.

the proposed escort duties. This is especially true when taking into account the fact that the submarine attacks extended towards Port Elizabeth and Durban later on in October.[21]

Fig 5.3: Vice Admiral (Sir) James Somerville – C-in-C Eastern Fleet (1942-1944)[22]

Fourth, by mid-1942, there was minimal air cover available over the extensive South African coastline. The situation was so dire that Smuts approached Churchill in an attempt to create awareness of the weak air cover over the vital sea route around the Cape of Good Hope. Smuts requested Churchill to have the deficiencies in South African equipment and aircraft addressed. In return, the Union would provide crews to operate the new aircraft. To some degree, the Joint Air Training Scheme, established in South Africa during the war, provided the required training to air and ground crews employed on coastal defence work.

Smuts also reminded Churchill of the vital importance of the maritime nodal point off Cape Town, and stated that it “is so vital to our war strategy that all provision against attack and even casual raids should be urgently made.”[23] Churchill subsequently instructed the Joint Planning Staff of the War Cabinet to investigate and prepare a report on the air defence of South Africa. Two successive reports from the Joint Planning Staff highlighted the dismal situation which existed in the Union regarding air defences. It also put forward some proposals to rectify the matter.

|

Location |

Existing Programme |

Proposed Programme |

|

Cape Town/Cape Peninsula |

1 X Fighter squadron 2 X TBR flights |

2 X Fighter squadrons 2 X TBR squadrons |

|

Port Elizabeth/East London |

1 X Fighter squadron 1 X TBR flight |

2 X Fighter squadrons 1 X TBR squadron |

|

Durban/Adjoining Area |

1 X Fighter squadron 1 X TBR flight |

2 X Fighter squadrons 2 X TBR squadrons |

|

South West Africa/Angola Littoral |

2 X TBR flights |

None |

|

Mozambique/East Africa Littoral |

3 X TBR flights |

1 X TBR squadron |

|

General Union Reserve |

1 X Fighter squadron 1 X Bomber squadron |

2 X Fighter squadron 1 X Bomber squadron |

|

Total Requirements |

4 X Fighter squadrons 3 X TBR squadrons 1 X Bomber squadron |

6 X Fighter squadrons 6 X TBR squadrons 1 X Bomber squadron |

Table 5.1: Proposed expansion of the SAAF in lieu of coastal defence, 1942[24]

By the end of May, the SAAF could account for only 27 operational aircraft within the Union to conduct coastal and other patrols. This number excluded training aircraft and those on operational duty across Africa, and consisted of Mohawks, Beauforts, Marylands and Ansons. The South African requirements were, however, somewhat unrealistic, notably since it proposed that the United Kingdom (UK) provide the SAAF with a further thirteen squadrons for use in the aerial defence of the Union (see Table 5.1).[25] The Joint Planning Staff provided a counter-proposal to Churchill, where they suggested that the provision of Venturas could provide the SAAF with both a coastal bombing and medium reconnaissance ability. They concluded that 36 Venturas were ready for immediate delivery to the Union from the United States of America and that a further 36 Venturas would follow suit. In addition to the 72 Venturas, the arrival of an Royal Air Force (RAF) Catalina squadron in South Africa would provide a further, muchneeded, long-range reconnaissance and offensive ability. Thus, by the time the Eisbär group struck off Cape Town, there was considerably more air cover available along the South African coast. Unfortunately, most of the SAAF crews remained untrained on the Venturas, especially in the general aspects of ASW.[26]

Fig 5.4: An RAF Catalina attached to Coastal Area Command at Durban.[27]

Last, before October, only a limited number of group sailings were in operation along the west coast of South Africa for ships travelling along the Cape Town–Freetown shipping route. Group sailings, by definition, comprised a number of merchant ships that travelled together in an attempt to reduce losses. Group sailings were, however, not escorted by naval vessels. When naval vessels escorted group sailings, it became a convoy. Air cover, whether complete or partial, interestingly, had no bearing on this definition.[28] By October the majority of the merchantmen had travelled independently along the South African coastline, in a general area up to 300 miles offshore. The size of the operational area that needed to be patrolled by South African and British naval and air forces on a daily basis was immense. This meant that protecting merchant shipping against U-boat attacks proved an exceptionally difficult, if not impossible, task. Moreover, the state of affairs in South Africa had worsened as a result of the limited air cover and naval escorts available.[29] Shortly before the Eisbär group launched their attacks off Cape Town, the Admiralty instructed Tait to order all vessels travelling through and approaching South African waters, to revert to travelling in groups with naval escorts when possible. The irony of this order was not lost to Tait. He simply did not have the required number of destroyers, corvettes, and trawlers under his command to provide the required escort duties.[30]

[1] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat material. Extracts from war diary U-159 (Helmut Witte), 24 Aug 1942 – 5 Jan 1943; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat material. Comments on war diary U 159 (Helmut Witte); DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat material. Report on my experiences on board U-68 on voyage to Cape Town from middle of August to middle of December 1942 by Walter Meyer.

[2] Kleynhans, ‘Good Hunting’, p. 174.

[3] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Extract from letter from Carl Emmermann on Operation Eisbär, 17 Oct 1953.

[4] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon-Cumming U-Boat Material. South Atlantic Station War Diary, Oct 1942; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341. File: U-boat matters. Operation Order “Eisbär”, 1 August 1942.

[5] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 79-80.

[6] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 174.

[7] http://www.saairforce.co.za/the-airforce/aircraft/171/b-34-ventura-ii (Accessed 11 June 2018).

[8] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon-Cumming U-Boat Material. South Atlantic Station War Diary, Oct 1942; Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 175. 527 Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 175.

[9] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 79-80; Kleynhans, ‘Good Hunting’, pp. 174-175.

[10] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 177.

[11] DOD Archives, CGS War, Box 122, File: Raiders. Most secret cable between DECHIEF and COASTCOM re sinking of German submarine off Cape Town, 9 Oct 1942.

[12] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-Boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters.

[13] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon-Cumming U-Boat Material. Extract from Proceedings of U-boat Assessment Committee (Volume 9), Sept-Dec 1942.

[14] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Emmermann (U-172) on Operation

Eisbär.

[15] https://uboat.net/men/commanders/1200.html (Accessed 3 May 2018).

[16] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters.

[17] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon-Cumming U-Boat Material. Report on U-boat Activities in South African Waters, Oct-Dec 1942; Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 168169.

[18] Kleynhans, ‘Good Hunting’, p. 173.

[19] Roskill, The War at Sea: Volume II – The Period of Balance, p. 270; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon-Cumming U-Boat Material. South Atlantic Station War Diary, Oct 1942; DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 127, File: Appreciations navy. C-in-C South Atlantic appreciation of the naval situation in the Cape area, 4 Oct 1942.

[20] DOD Archives, CGS War, Box 38, File: Blackouts and lighthouses. Correspondence between Tait and Van Ryneveld re coastal blackouts, 19 Jun 1942; DOD Archives, CGS War, Box 38, File:

[21] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon-Cumming U-Boat Material. South Atlantic Station War Diary, Oct 1942.

[22] https://za.pinterest.com/pin/328833210276773262/?lp=true (Accessed on 29 June 2018).

[23] TNA, CAB 84/46, Air Defence on South Africa and Madagascar. Personal Telegram from Smuts to Churchill, 5 Jun 1942.

[24] TNA, CAB 84/46, Air Defence on South Africa and Madagascar. Note by the Secretary of the Joint Planning Staff on the South African Air Force, 12 Jun 1942.

[25] TNA, CAB 84/46, Air Defence on South Africa and Madagascar. Report by the Joint Planning Staff on the Air Defence of South Africa and Madagascar, 7 Jun 1942; TNA, CAB 84/46, Air Defence on South Africa and Madagascar. Note by the Secretary of the Joint Planning Staff on the South African Air Force, 12 Jun 1942.

[26] TNA, CAB 120/474, South Africa: correspondence with Field-Marshal Smuts. Note to Prime Minister on Air Defence of South Africa, 16 Jun 1942; TNA, ADM 1/12101, Anti-U-boat warfare. Measures required to meet the U-boat threat in South Atlantic, 7 Dec 1942.

[27] South African National Museum of Military History, Masondo Reference Library. SA Navy Photo Collection, S.A. 5219.

[28] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon-Cumming U-Boat Material. Miscellaneous notes, undated.

[29] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 339, File: Gordon Cumming U-boat material. The Commanders-inChief South Atlantic and Eastern Fleet, Report on the safety of shipping in South African waters, 30 Mar 1943.

[30] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 169.