THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

24)THE MARITIME INTEL WAR IN S AFR

The maritime intelligence war in southern Africa, 1939-1945

Introduction

Maritime intelligence played a crucial role during the course of the naval war in South African waters. Following the outbreak of the war, Germany attempted to initiate covert contact with the South African political opposition on several occasions.

After establishing viable radio contact with Germany, the Ossewabrandwag (OB) – which translates to Ox-wagon Sentinel, an anti-British and pro-German organisation, in particular started transmitting both political and military intelligence to Berlin. Subsequent to the establishment of the FELIX Organisation in mid-1942, there was a marked increase in maritime intelligence gathered by the OB and relayed to Berlin. The operational value of this source of maritime intelligence, however, remained questionable for the remainder of the war in southern Africa. The Cape Naval Intelligence Centre (CNIC) proved the main player in the Allied sphere of maritime intelligence in southern Africa during the war. The CNIC formed a vital link in the overall Allied maritime intelligence organisation during the war. It did so by presiding over both operational intelligence and counterintelligence during the prosecution of the naval war off the South African coast.

Chapter four has three broad objectives, the first of which is to investigate instances of sabotage and subversion within the naval sphere in South Africa during the war. This will occur predominantly in the context of the initial operational contacts established between the OB and Germany during the first few years of the war. The second aspect involves a critical discussion of the role, functioning and effectiveness of the FELIX Organisation in southern Africa during the war. Here, the particular focus is on the Organisation’s contribution to the gathering and distribution of maritime intelligence to Germany. Finally, the purpose, organisation, and success of the CNIC in southern Africa during the war will be examined. Specific emphasis will be placed on the operations of each of its core sections – Tracking, Operational Intelligence, Security, Naval Press Relations and Censorship.

4.1 Sabotage, subversion and the initial South African contacts with Germany

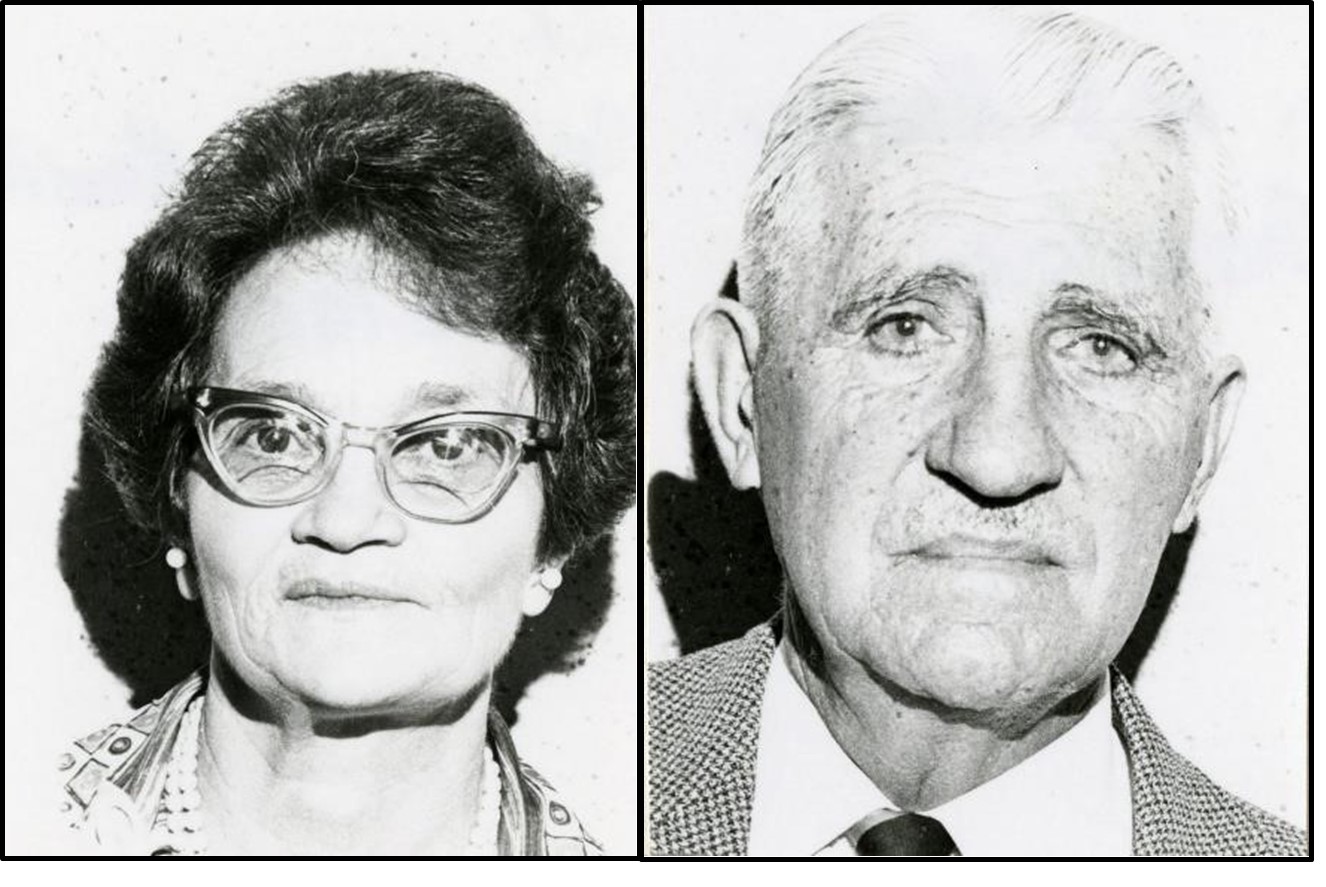

Piet van der Schyff, erstwhile historian and archivist of the OB,[1] argues that two pertinent questions arise regarding the OB and its possible contact with Nazi Germany during the war. First, was there definite contact between the OB and Germany during the war? Second, if such contact existed, what was the nature and extent thereof? The answer to the first question is straightforward. The OB maintained regular contact with Germany throughout the war, mainly due to its pro-Nazi and anti-British stance. The second question, however, needs further investigation, especially with regard to how it related to the maritime intelligence war waged in southern Africa.[2] The first definite contact established between Germany and the OB was through Will and Marietjie Radley. They were a South African couple who was unable to leave Germany after the declaration of war. The Radleys had become involved in the German propaganda machine when they joined the broadcasting corps of Radio Zeesen, which transmitted anti-war propaganda to South Africa.[3] In January 1940, Dr Rudolph Karlowa, a senior diplomat at the German Foreign Ministry, summoned the couple. He requested that Marietjie return to South Africa with a message from the German Government to the leader of the official parliamentary opposition in the Union. After careful investigation of the political situation within South Africa, the German Government decided to support Dr D.F. Malan and his National Party.

Their decision was a result of the perceived negligible influence of Barry Hertzog and Dr Hans van Rensburg.[4] The Radleys subsequently agreed to the request, whereafter Marietjie memorised the following message:

Die Duitse Ryksregering sal by voltrekking van vrede met die Unie van SuidAfrika, sy nasionale gebied erken en waarborg, soos dit bestaan uit die Kaap Provinsie, Oranje Vrystaat, Transvaal en Natal, sowel as [die] drie protektorate, Swaziland, Basutoland en Bechuanaland. Die

Duitseryksregering sal [ook] verklaar dat Duitsland nie sal belangstel indien die Unie van Suid-Afrika sy nasionale gebied sal uitbrei tot wat vandag bekend staan as Suid Rhodesië nie. Duitsland oorweeg nie die totstandkoming van ʼn aparte staat op Afrikaanse bodem nie, en erken die Unie van Suid-Afrika as die leidende blanke staat in die Suid-Afrikaanse lewensruimte.

The German Government will, upon the declaration of peace with the Union of South Africa, recognise and guarantee its territorial sovereignty, comprising the Cape Province, Orange Free State, Transvaal and Natal, along with the three protectorates of Swaziland, Basutoland and Bechuanaland. The German Government will also have no reservations should the Union of South Africa decide to increase its territory by incorporating Southern Rhodesia. Germany is not considering the establishment of a separate state in Africa, and recognises the Union of South Africa as the leading white state in the South African sphere of influence.[5]

Marietjie Radley travelled to South Africa during the middle of February. After failing to make contact with Malan, she instead delivered the message to Van Rensburg, the soon-to-be leader of the OB. Van Rensburg promised to pass it onto Malan. The message, however, never reached Malan, and the German Foreign Office subsequently asked Will Radley to deliver a follow-up message to him. If Radley failed to meet with Malan, the message could be passed on to Van Rensburg for later delivery to Malan.[6] The details of the second message were as follows:

Die Duitse Regering herbevestig sy voorneme en aanbod aan die SuidAfrikaanse Volk soos vervat in die onderneming wat deur mev. Marie Radley oorgedra is in Januarie 1940.

Indien ʼn gewapende opstand teen die oorlogspoging sou ontstaan in SuidAfrika, en die opstandelinge wapens benodig, kan Duitsland die wat vry geword het nadat die Spaanse Burgeroorlog ʼn aantal maande tevore ten einde geloop het, bekom en voorsien. Hoewel nie nuut nie is dit nog goed bruikbaar en dit kan in Noord-Afrika afgelewer word om dan verder self vervoer te word. Van sy eie wapens kon Duitsland egter niks afstaan nie aangesien dit alles tuis benodig word.

Die Duitse Regering sal graag kontak met die opstandsbeweging wil hou, en hulle is welkom om probleme te bespreek.

The German Government reconfirms its intentions and offer to the South African nation that which was contained in the message passed on by Mrs. Marie Radley in January 1940.

In the event of possible armed resistance breaking out against the war effort in South Africa, and if weapons be required for the resistance, Germany is able to obtain and provide weapons used during the Spanish Civil War that has ended some months before. Despite not being new, the weapons are still serviceable and can be delivered to North Africa from where they can then be transported south through own means. Germany is unable to deliver its own weapons as they are needed on the home front.

The German Government wishes to maintain contact with the resistance movement, and it is welcome to discuss its problems.403

Will Radley arrived in South Africa on 6 May 1940. With the South African Police (SAP) in hot pursuit, he made for Bloemfontein. Here Radley, like his wife, delivered the message to Van Rensburg with a request that he pass it on to Malan. Radley was, however, arrested and interned. In spite of this, he was released in December after agreeing to distance himself from any subversive activities.

This second message thus initially failed to reach Malan. By December, Radley managed to personally deliver the same message to Malan, who read it but never acted upon it.[7] As to why Malan never acted on the German offer, Radley has the final word: “[Dit] kon eindelose smart en bloedvergieting tot gevolg gehad het, met baie onsekere kanse op sukses… ek dink nie dat Dr Malan met die boodskap wat ek gebring het enige iets sou kon of sou wou uitrig nie.” [... It would have caused endless sorrow and bloodshed, with very slim chances of success… I also don’t think that Dr Malan could have or would have wanted to do anything with the message that I passed on to him.]”[8]

Fig 4.1: Marietjie and Will Radley – couriers between Germany and South Africa[9]

There is some evidence suggesting that a rudimentary German espionage organisation existed in Cape Town, and for that matter, the whole of South Africa, during 1940. Hendrik Hickman, who worked at the Globe Engineering Works in Cape Town harbour at the time, made known that a secret organisation employed him to report on all shipping that passed through the port. A student from the University of Cape Town, one ‘Rehbein’, acted as Hickman’s handler throughout 1940. Hickman was, however, rather uncertain of the command structure of the organisation he worked for. Of what he was certain, though, was that the organisation comprised of ardent Nazis and national socialists.

Hickman’s employment in the port evidently aided his surveillance of Allied shipping. He reported his findings every night via a signal lamp from his home in Somerset West towards the Helderberg. His messages included the names of the individual Allied vessels, their departure time from the port, and in which direction they were travelling. Hickman reported that he had been aboard HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse. He was furthermore convinced, rather unrealistically, that his reports on these vessels had led to their sinking by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) soon thereafter.

While working at the docks, Hickman also regularly helped to sabotage Allied vessels in the harbour through structural or mechanical damage. In 1941, however, he discontinued his work on the Cape Town docks, as well as ending his covert reporting on shipping. He did so in order to commence his studies at Stellenbosch University, where he became an active member of the OB. Hickman’s testimony is, withal, somewhat problematic. He maintained that he worked on the docks and reported on a large number of Allied shipping that was sunk near Cape Point. This, however, could only have occurred during the operations of the Eisbär Group in October 1942 (see Chapter 3, page 110). At that stage he was already a student at Stellenbosch University.[10]

German Intelligence next attempted to establish contact with the South African opposition through Hans Rooseboom. Rooseboom was a German-born South African journalist who, like the Radleys, was unable to exit Germany after the outbreak of the war. In September 1940, the Abwehr – German military intelligence – recruited Rooseboom as an agent. He was ordered to travel to South Africa and report back on the internal political situation in the Union. He was to maintain contact with Germany through a contact in the Netherlands.[11] Rooseboom’s arrival in the Union did not go unnoticed by the British Secret Intelligence Service. The British Secret Intelligence Service – more commonly known as MI6 –followed his movements closely.

The fall of the Netherlands in May 1940 severed Rooseboom’s original link with Germany, and he had to re-establish contact with the Abwehr through the German Embassy in Lourenço Marques. Shortly hereafter, the SAP arrested Rooseboom and imprisoned him at Leeuwkop Internment Camp. During his confinement, Rooseboom was able to establish contact with Germany through a smuggled-out message passed on to a stewardess on the Woermann Shipping Line. The message not only reported his capture and subsequent internment, but also communicated shipping movements and the so-called unrest at Baviaanspoort.[12] Two days after delivery of the message to the Abwehr, Radio Zeesen broadcasted the information which Rooseboom had divulged. As a result of this broadcast, the Transvaal leadership of the OB approached Rooseboom with a request to act as their official contact with Germany. Rooseboom agreed to the request, and the OB organised his escape, after which he went into hiding. He subsequently built up a rudimentary intelligence organisation, and sporadically transmitted messages from the OB to Germany.[13]

The first particular message which the OB transmitted to Germany through Rooseboom comprised seven specific questions and requests from the South Africans regarding Germany’s attitude to the Union. They were:

Sal Duitsland die Unie beset as hy die oorlog wen?

Sal Duitsland skadevergoeding van Suid-Afrika eis?

Sal Duitsland Simonstad opeis, soos die Engelse?

Wat is Duitsland se planne jeens Suidwes Afrika?

Dat Smuts en sy helpers as oorlogmisdadigers verhoor sou woord.

Dat die mishandeling van krygsgevangenes in Baviaanspoortkamp volledig ondersoek en die skuldiges gestraf sal word.

Dat, wanneer ʼn nuwe regering in die Unie aangewys word, Duitsland voorlopig en na onderlinge oorleg goedkeuring moet verleen aan die nuwe Eerste Minister of President.

Would Germany occupy South Africa if they won the war?

Would Germany claim damages from South Africa?

Would Germany, like Britain, take control of Simon’s Town?

What are Germany’s plans for South West Africa?

Smuts and his supporters should be tried as war criminals.

That a full investigation must be launched into the mistreatment of internees at the Baviaanspoort Camp, and the guilty parties must receive the appropriate punishment.

That upon the election of a new Union Government, Germany authorise the appointment of a new South African Prime Minister or President.[14]

The German response to the foremost OB questions was as follows:

Nee, Duitsland sal nie Suid-Afrika beset nie, maar hulle eis dat ʼn goedgesinde Nasionale regering aan bewind sal kom en dat daar behoorlike samewerking moet wees. Alleen as so ʼn Nasionale regering dit verlang, sal Duitsland bereid wees om troepe te stuur.

Duitsland sal wel skadevergoeding eis, maar dan as belasting uitsluitend vir alle persone wat nie kan bewys dat hulle ʼn nasionale beweging in SuidAfrika ondersteun het nie, dat hulle teen oorlogsdeelname was.

Nee, Duitsland is bewus daarvan dat dit vir Suid-Afrika ʼn pynlike saak is, dat daar ʼn vreemde moondheid op hulle grondgebied is. Hulle sal Simonstad ontruim en aan die SA Vloot oorlaat, maar as dit nodig sou word, sou hulle ʼn ooreenkoms met Suid-Afrika aangaan om een van die eilande voor die kus as basis uit te bou.

Duitsland eis ʼn verklaring waarin Suid-Afrika erken dat Suidwes-Afrika onwettig en onder valse voorwendsels van Duitsland afgeneem is, en dat dit in beginsel aan Duitsland teruggegee word. Onder heersende omstandighede en vanweë baie Afrikaners in die gebied, sou hulle eis dat Duits as ʼn landstaal erken word en dat ʼn ooreenkoms aangegaan sal word oor watter regte Duitsland en Suid-Afrika daar sou uitoefen.

No, Germany will not occupy South Africa, but they demand that a Nationalist government assume power to ensure good cooperation. Germany will only send troops at the request of the Nationalist government.

Germany will claim war damages in the form of a tax, but only from people who cannot prove that they were part of a nationalist movement in South Africa or against the war in general.

No, Germany is aware that it is a terse point for South Africa that a foreign power has a foothold on its territory. It will evacuate Simon’s Town and leave it to the South African Navy, but if necessary, it will come to an agreement with South Africa to establish a base on one of the islands off the South African coast.

Germany demands a statement from South Africa in which it acknowledges that South West Africa was illegally taken from Germany and that it should be returned to Germany in principle. Due to the prevailing conditions, and because of a significant number of Afrikaners in the territory, Germany demands that German be recognised as an official language. Germany also demands an agreement with South Africa regarding who will exercise which powers in the territory.[15]

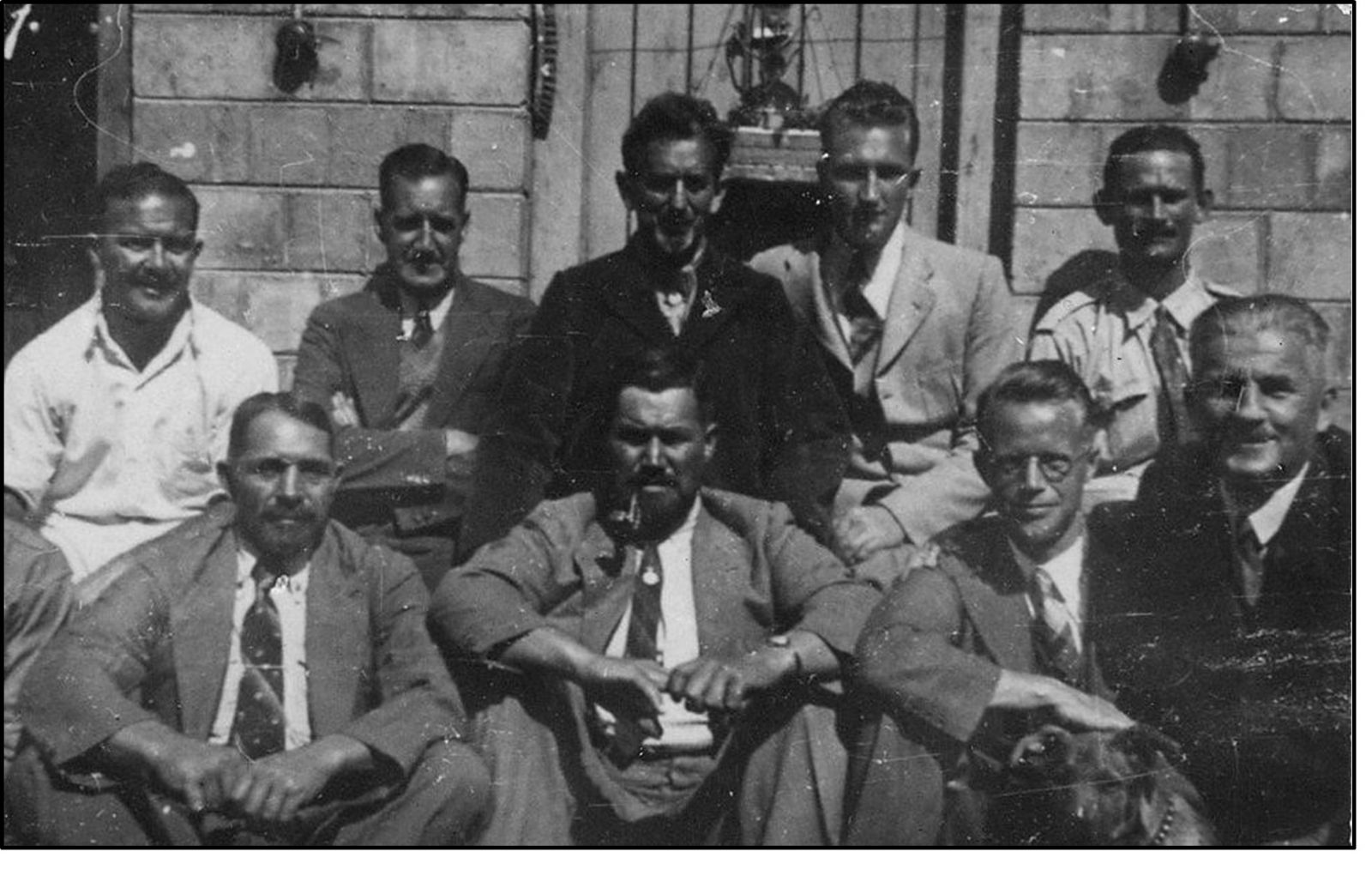

Fig 4.2: Hans Rooseboom, front row, second from right, while interned at Leeuwkop[16]

Hans Rooseboom, codename PETERS,[17] became the principal link through which the OB maintained regular contact with Germany during the first few years of the war. Initially, coded messages sent to Lourenço Marques appeared as death notices in English newspapers – principally the Sunday Times. Once a homemade radio transmitter became operational, Rooseboom ceased to use the English newspapers as a means of covert communication. The mere turn-around time of intelligence passed between the Union and Lourenço Marques via the Sunday Times had proved problematic, especially as it was outdated by the time it arrived in Berlin. Some of the information that Van Rensburg and the OB passed on to Rooseboom for transmission to Germany involved the movement of Allied shipping along the South African coast. Van der Schyff writes about this, but does not elaborate on the extent of this information. He merely adds that Van Rensburg never reported on the movement of shipping that carried South African soldiers.[18]

The Rooseboom Organisation effectively operated between April 1941 and March 1942, until an apparent dispute between Rooseboom and elements within the OB occurred. The primary cause of this disagreement was that Rooseboom and Van Rensburg had a difference of opinion on the military and political character of news passed on to Lourenço Marques.[19] The arrival of Lothar Sittig, codename FELIX, during 1942, was the second cause underlying the Rooseboom dilemma. This was because Rooseboom was the preferred agent through whom the OB hoped to maintain contact with Germany.[20]

By the latter half of 1942, Van Rensburg had tasked one of his most trusted lieutenants, Heimer Anderson, to assume complete control over all OB communications with Germany. Anderson, along with Sittig, did not get on well with Rooseboom, and vehemently distrusted him.[21] Due to this mistrust, Anderson advised Van Rensburg to sever all contact with Rooseboom. Despite several attempts by Rooseboom to contact the OB leadership and plead his case, the OB officially distanced themselves from him. The organisation even contemplated his assassination should he turn state-witness.

Rooseboom went underground for the remainder of the war. For some time after September 1942, he operated a separate radio transmitter with Herbert Wild on a farm between Pretoria and Johannesburg, though the nature and extent of his communications with Germany during this period remain unclear. Rooseboom apparently made a deal with the Smuts Government at the end of the war not to prosecute him, as neither the British or South African security services arrested or interrogated him.[22] The nature and effectiveness of the Rooseboom organisation remain questionable, particularly regarding the naval intelligence war, since MI6 only picked up on his activities in mid-1942.

The formation of the militant Stormjaers movement within the OB during February 1940, thanks to the untiring efforts of Abraham Spies in particular, signalled the beginning of organised sabotage and subversion within South Africa. Spies ordered each of the OB Commandos within the Transvaal and Free State to create a core section of Stormjaers within their ranks. The Stormjaer movement never found favour in the Cape Province, and a so-called ‘Wag-afdeling’ [guard section] was instead established. The Stormjaers and Wag-afdeling, however, never cooperated, and functioned completely independently of one another.[23]

A former policemen, George Visser, provided an accurate description of the aim of the movement. He said, “Just as the German Nazi Party had the Schutz Staffel – SS – so had the Ossewabrandwag the Stormjaers ready to storm forward as their militant action front when the time seemed ripe.”[24] Van Rensburg, while acknowledging the existence of the Stormjaers, described them as a parallel movement: “… they were half in and half out of the O.B. Let us call it parallel to and connected with! They numbered some seven or eight battalions, carrying on a semi-independent and hardly peaceful existence.”[25] Spies is more direct when he states, “The Stormjaers [were] actually organised to be ready to execute a coup d’état in the case of a German victory, or to conduct active resistance against Smuts.”[26]

The Stormjaers were undeniably involved in acts of sabotage and subversion in South Africa throughout the war. These actions often involved theft, occasional murders, the planting of bombs, the cutting of telegraph wires, and to assist with numerous escape and evasion attempts from internment camps.424 The Stormjaers may have conducted several minor acts of sabotage at South African harbours during the war similar to that which Hickman described. But there was at least one notable incident of attempted sabotage in the naval sphere that could have held serious repercussions for both the Allies and South Africa had it succeeded.

By mid-1942, two members of the Stormjaers, Kokkie van Heerden and Dawid Scribante, travelled to Durban. Their objective was to blow up the Durban Graving Dock. Van Heerden and Scribante conducted active surveillance of the Durban Graving Dock, whereafter they started to stockpile enough dynamite and clocks to enable delayed detonations. At this stage, their target was the SS Île de France, a French ocean-liner, which was in the Durban Graving Dock for refit and repairs. The two men managed to get to the wire fence surrounding the Graving Dock, but then realised that the planting of the explosives would prove far too dangerous as the approaches were well lit. They did not make another attempt at blowing up the Graving Dock, and subsequently buried the explosives in the backyard of the house of an OB supporter in Durban. While this act of sabotage was unsuccessful, it proves the sheer vulnerability of the South African ports during the war – where OB and Stormjaer men, often working for the Union Government, could pass in and out of sensitive areas of key national importance with the explicit intention of committing acts of sabotage. [27]

[1] For more information on the Ossewabrandwag see Marx, Oxwagon Sentinel; Van der Schyff, Geskiedenis van die Ossewa-Brandwag.

[2] Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, p. 96.

[3] Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, p. 101. For more information on Radio Zeesen and its radio transmissions to South Africa during the war see NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. Dr Eric Holm. Also see Marx, ‘Dear Listeners in South Africa’, pp. 148-172. The DOD Archives contains a virtually complete collection of the Zeesen broadcasts, contained in the Zeesen Broadcasts WW II archival group (consisting of 15 archival boxes worth of documents, covering the period 1941-1945).

[4] Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, pp. 101-102.

[5] Radley and Radley, Twee Poorte, pp. 28-29.

[6] Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, p. 102. 403 Radley and Radley, Twee Poorte, p. 109.

[7] Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, p. 103. Incidentally, these two German attempts to contact Malan so early in the war evaded his most recent biographer, Lindie Koorts. See Koorts, DF Malan and the Rise of Afrikaner Nationalism.

[8] Radley and Radley, Twee Poorte, p. 110.

[9] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Photo Collection. F00660_3 – M. Radley; NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Photo Collection. F00660_5 – W. Radley.

[10] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. H.T. Hickman.

[11] Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, pp. 103-104. For more on Hans Rooseboom’s journey back to South Africa, which unfortunately contains no information about his contact with the Abwehr, see Rooseboom, Die Oorlog Trap My Vas.

[12] TNA, KV 2/941, Rooseboom, Hans. 46a – Extract from CSDIC/WEA Final Report on AHLRICHS re ROOSEBOOM, 4 Feb 1946. The unrest at Baviaanspoort, or as some Afrikaans sources state – ‘Die slag van Baviaanspoort’, originated when the internees refused to surrender one of their own to the camp authorities. After a tense stand-off, the UDF surrounded the camp and forcefully removed the internee they were after. The internees severely criticized the UDF for their forceful approach during the debacle, though they have failed to mention that they themselves were armed and fought back. It was hoped that Rooseboom’s message would in some way orother generate support and empathy for the internees at Baviaanspoort.

[13] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. Hans Rooseboom.

[14] Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, pp. 104-105; NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. H. Rooseboom.

[15] Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, p. 105. NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname.

[16] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Photo Collection. F00005_3 – H. Rooseboom.

[17] Visser, OB: Traitors or Patriots?, pp. 88-90. Visser, interestingly, fails to identify PETERS as Rooseboom in the book.

[18] Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, p. 105. For more information on the homemade radio transmitter see: NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive,

Transkripsies/Bandopname. J.H. Barnard.

[19] TNA, KV 2/941, Rooseboom, Hans. 43a – Copy of Interim Report on MASSER, mentioning ROOSEBOOM, 26 Oct 1945; TNA, KV 2/941, Rooseboom, Hans. 44a – Copy of Interim Report on Walter Paul Kraizizek, 31 Oct 1945.

[20] Visser, OB: Traitors or Patriots? p. 90.

[21] For more on Van Rensburg’s distrust of Rooseboom and their dispute see NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. J.H. McDonald; NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. L. Sittig; NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. H.J.R. Anderson.

[22] TNA, KV 2/941, Rooseboom, Hans. 11a – Copy of cable received from Pretoria re ROOSEBOOM, SITTIG and MASSER, 27 Jul 1943; TNA, KV 2/941, Rooseboom, Hans. 13a – Extract from BIB report on German Espionage in the Union of South Africa re ROOSEBOOM, 25 Sept 1943; TNA, KV 2/941, Rooseboom, Hans. 37a – Copy of information from BJ 135893.

[23] Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, pp. 83-87.

[24] Visser, OB: Traitors or Patriots?, p. 29.

[25] Van Rensburg, Their Paths Crossed Mine, p. 184.

[26] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. A.S. Spies; NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. J.H. McDonald. The original Afrikaans text reads: “Die SJ’s was eintlik georganiseer… om gereed te wees vir [wanneer] die Duitse oorwinning nou vir ons die geleentheid gee om hier ʼn staatsgreep uit te voer of in aktiewe opstand teen Smuts te kom.” 424 Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, pp. 93-95.

[27] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. D.J.F. Scirbante.