THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

20)RAIDERS OFF SOUTH AFR COAST

Chapter 3 Axis raiders, mines and submarines off the South African coast, 1939-1945

Introduction

At the outbreak of the Second World War, the German High Command reached an important conclusion. It understood that the survival of Britain and the success of the Allied war effort were entirely dependent on the hauling of key logistical supplies by merchant shipping from across the British Empire over vast, often unprotected, sea lanes. If the Axis naval forces simply controlled the oceans and further ensured that the sinking of Allied commercial shipping outnumbered the capacity to replace them, the Allied war effort could effectively be crippled.

During the war itself, the German naval focal point was the North Atlantic, while the Japanese naval focus was on the Indian and Pacific oceans. At times, sporadic naval operations were launched in more remote waters in the hope of achieving good sinking results and dividing Allied naval forces. When the sinking results in the North Atlantic area decreased due to effective Allied anti-submarine (A/S) measures, the Axis leadership strategically decided to launch a series of concentrated maritime operations in the South Atlantic and the western Indian Ocean. South African waters would become a particular target of this activity. The ensuing Axis naval operations thereupon managed to throw merchant shipping off the South African coast into disarray. It forced the Allies to focus their naval attention on the remote area off southern Africa to safeguard its merchant shipping.

This chapter has three specific objectives. First, it will investigate the operational successes of the Axis raiders and mines off the South African coast between 1939 and 1942. The second objective is to critically discuss the limited Japanese submarine operations in the Mozambican Channel in 1942. This discussion will take place in the context of the strategic German-Japanese Naval cooperation in the western Indian Ocean. Finally, the Axis submarine operations in South African waters – particularly the sustained U-boat operations from 1942 to 1943 – will be evaluated from a strategic point of view. This chapter thus provides fresh perspectives on the Axis maritime operations in South African waters during the war.

3.1 Raiders, mines and opportunistic attacks

In August 1939, GAdm Erich Raeder, the Commander-in-Chief of the German Navy (Oberbefehlshaber der Marine) anticipated the looming outbreak of war. He thus instructed his pocket-battleships to focus their operational efforts on the disruption and destruction of Allied merchant shipping. This was to be done according to the Prize Regulations[1] of the Kriegsmarine. Raeder further warned his officers to avoid an engagement with Allied naval forces except when it would further their key task of economic warfare. He emphasised that the pocket-battleships extend their operations to distant waters. This would mislead their opponents and create a general state of uncertainty.

Fig 3.1: Grand Admiral Erich Raeder[2]

Raeder was, however, certain to caution that the principal aim of their deployment was not the mere destruction of merchant tonnage. If the operations could force the Allied navies to protect their merchant shipping with superior forces, the sheer restriction of merchant shipping would greatly impair the Allied supply situation. Both the Graf Spee (Langsdorff) and Deutschland (von Fischel) left Wilhelmshaven towards the end of August and journeyed to the mid-Atlantic where they awaited further instructions.

After the war broke out, Raeder ordered the pocket-battleships to withdraw from their operational areas in light of France and Britain’s initial military and political restraint during the first month of the war. The Graf Spee subsequently travelled to the South Atlantic, where it remained most of September. On 23 September, however, Raeder informed Adolf Hitler that he would soon need to commit the pocket-battleships to active operations. This was because the inactivity affected both the supplies and the morale of the men. Hitler conceded, and on 26 September the Graf Spee and Deutschland were ordered to attack British shipping. The Deutschland, however, soon returned to Germany without any real operational accomplishments.[3]

In the first week of October, the Graf Spee sank the Clement (5,501 tons) off the coast of Brazil. It then journeyed nearly 2,000 miles eastwards to operate in the midSouth Atlantic and off the west coast of Africa. Between October and December, the Graf Spee frequently relocated between the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans when the Allied naval pressure became too strong in either. It did, however, manage to sink five merchantmen in South African waters. They were the Ashlea (4,222 tons), Trevanion (5,299 tons), Africa Shell (706 tons), Doric Star (10,086 tons) and the Tairoa (7,983 tons). Over a period of ten weeks, the Graf Spee effected the sinking of a total of nine British ships that sailed independently, totalling 50,089 tons lost. Of this figure nearly 56% was sunk in South African waters, constituting 28,296 tons.[4]

On 14 December, however, the Graf Spee was shadowed by the British cruiser HMS Exeter, supported by the cruisers HMS Ajax and HMS Achilles, near the River Plate off Argentina in the South Atlantic. Although Raeder initially discouraged his pocketbattleships from engaging Allied warships, Langsdorff opted to attack and soon opened fire on his pursuers. A fierce naval engagement followed, during which HMS Exeter was severely damaged. After several critical hits from HMS Exeter, specifically to its oil filter system, the Graf Spee soon broke off contact and made for neutral waters and the relative safety of Montevideo harbour in Uruguay. During the next few days, carefully, planted British reports – especially the fictitious arrival of the carrier HMS Ark Royal and the battlecruiser HMS Renown – convinced Langsdorff that escape into the open sea from Montevideo was infeasible. Hitler and Raeder subsequently agreed that Langsdorff should attempt to break through the blockade, but Hitler was not eager for Langsdorff to scuttle the battleship. The final decision was, however, left to Langsdorff.

On the afternoon of 17 December, he decided to scuttle the Graf Spee soon after leaving port.[5] The Oberkommando der Marine further deployed approximately 26 disguised raiders,[6] officially termed ‘auxiliary cruisers’ during the Second World War (see Table 3.1). The Seekriegsleitung (SKL) adopted a specific policy with regard to the initial operational employment of the disguised raiders. Their chief aim was to divert Allied naval forces from their home waters and to inflict damage to shipping. This would be executed by forcing the Allies to adopt convoys and to deploy strong naval forces along trade routes in remote waters. They would also coerce the Allies into constantly employing their naval forces; scare away neutral shipping, and create a situation harmful to the Allies from an economic and financial point of view. Raeder hence gave the captains of the disguised raiders three instructions. They were to change their operational areas continually so as to surprise Allied shipping where least expected, not to attack escorted convoys, and to avoid any inevitable action with Allied naval forces. The disguised raiders were also ordered to wage their war against merchant shipping strictly according to the established Prize Regulations.[7]

|

NAME |

ATLANTIS |

THOR |

PINGUIN |

MICHEL |

KOMET |

|

Ops Number |

SCHIFF 16 |

SCHIFF 10 |

SCHIFF 33 |

SCHIFF 28 S |

SCHIFF 45 |

|

Displacement |

7,860 GRT |

3,862 GRT |

7,766 GRT |

8,000 GRT |

3,200 GRT |

|

Surface Speed |

16knots (29.6 km/h) |

18knots (33.3 km/h) |

17 knots (31.5km/h) |

14.8knots (27.4 km/h) |

14.8knots(27.4 km/h) |

|

Crew |

349-351 men |

349 men |

401 men |

395 men |

274 men |

|

Armament |

6 x 15 cm ; 1x 7,5 cm; 2 x 3,7 cm; 4x 2 cm AA; 4 x torpedo tubes |

6 x 15 cm; 1x 6 cm; 2 x 3,7 cm; 4x 2 cm AA; 4 x torpedo tubes |

6 x 15 cm; 1x 7,5 cm; 2 x 3,7 cm; 4x 2 cm; 2 x torpedo tubes |

6 x 15 cm; 1x 10,5 cm; 4 x 3,7 cm; 4 x 2 cm; 6 x torpedo tubes |

6 x 15 cm; 1x 6 cm; 2 x 3,7 cm; 4 x 2 cm; 6 x torpedo tubes |

|

Miscellaneous |

2 x Heinkel He 114 float planes; 92 mines |

1 x Arado Ar 196 float planes |

2 x Heinkel He114 float planes; 300 mines |

2 x Arado Ar 196 float planes; 1 x LS4 boat |

2 x Arado Ar 196 float planes; 1 x LS2 boat; 30 Mines |

Table 3.1: Statistical data of German raiders operational in South African waters[8]

The first operational disguised raider, the Atlantis (Rogge), left for the Cape and the Indian Ocean at the end of March 1940. The Thor (Kähler) followed in June, and also headed for the South Atlantic. The operational area of the Atlantis’ comprised of the western Indian Ocean as far as 80° East. It was also allowed free reign in the eastern Indian Ocean, the South Atlantic and Australian waters as alternative operative areas. Its priority, however, was to mine the waters off Cape Agulhas and Cape St Francis on the South African coast. After that, it was instructed to mine the waters off Madagascar, especially near Fort Dauphin and Cape Ste Marie. During his voyage south, Rogge was not allowed to attack merchant shipping until he reached the trade route between Freetown in Sierra Leone, and the strategic maritime nodal point at the Cape of Good Hope. At this stage, Freetown served as an assembly point for all merchant shipping travelling to and from Europe, South America, the Middle East and the Far East. At Freetown, the slower merchantmen formed into convoys for their onwards journey, while the faster ships sailed independently.[9]

On 3 May, Atlantis sank the Scientist (6,199 tons), but not before its wireless operator dispatched a ‘QQQQ’ signal.[10] This signal was not picked up. The Atlantis arrived off Cape Agulhas on 10 May after doubling back along the shipping route from Australia. Throughout the night, the Atlantis dropped mines at six-minute intervals all along the coast of Cape Agulhas following a zig-zag course. During the evening, 92 mines were dropped in an area 5-20 miles off shore. The minefield was discovered by the keeper of the Agulhas lighthouse on 13 May after he witnessed a heavy explosion out to sea. This minefield, however, failed to damage any ships during the war.[11]

After the first successful mining operation off Cape Agulhas, Atlantis moved further north-east to operate along the Durban-Australia route. After a report that a raider disguised as a Japanese merchant ship was active in the Indian Ocean, the Atlantis changed her appearance to that of a Dutch merchantman. By the end of May, she relocated to the north to operate off the Durban-Batavia and Fremantle-Mauritius routes. Here she had some operational successes.[12] The Italians entered into the war on 10 June. This held grave consequences for Allied shipping through the strategic Suez Canal. British seaborne communication between the two vital campaign areas at the time – the Middle East and the Far East – was essentially severed. As a result, all vessels travelling to and from Britain and the Far East now had to traverse the longer route around the Cape of Good Hope. This added an estimated 10,000 sea miles to a voyage. Shipping was also more prone to attack by German and Italian raiders and submarines along these vast trade routes.[13] By July, the Pinguin (Krüder) arrived in the South Atlantic, disguised as a Greek merchant vessel. The Pinguin was initially designated to operate in the Indian Ocean and Australian and Antarctic waters, with the Pacific and South Atlantic as alternatives. It was further instructed to lay mines off the coasts of Australia, India, South Africa and Madagascar.

By the end of July, the SKL authorised Krüder to operate in the Cape waters while en route to his allotted area of assignment.[14] On 26 August, Atlantis successfully attacked and captured the Norwegian merchantman Filefjell (7,616 tons) 300 miles to the south of Madagascar. Shortly after that, it sank the British Commander (6,901 tons) and the Morviken (5,008 tons). After these successes, Krüder was forced to exit the area after intercepting a radio message from Durban which revealed his presence. In an over-hasty decision, he decided to sink the Filefjell.[15] The Pinguin subsequently relocated to an area 900 miles east-south-east of Madagascar to lie low. Unknown to Krüder, the Atlantis was also operational throughout August and September. Both Rogge and Krüder received a stern dressing down from SKL; Rogge for encroaching on Krüder’s operational areas, and Krüder for not relocating to a new operational area quickly enough. Both the Atlantis and Pinguin subsequently relocated to the Sunda Straits, where they continued offensive operations independently. The Pinguin afterwards journeyed to Australian waters where it and one of her captured prizes, the Passat, successfully mined the Bass Strait.[16]

In October, the pocket-battleship Admiral Scheer (Krancke) journeyed towards the South Atlantic. Here she rendezvoused with Thor on Christmas Day approximately 600 miles to the north of the island of Tristan de Cunha. The codename for this secret rendezvous area was ‘Andalusien’.[17] On 17 January 1941 Krancke captured the tanker Sandefjord (8,038 tons), whereafter it sank the Stanpark (5,103 tons) and Barneveld (5,597 tons) on 20 January. After replenishing from the tanker Nordmark at Andalusien, Krancke decided to exploit the lucrative waters of the Indian Ocean. After successfully rounding the Cape of Good Hope, the Scheer reached the Durban-Australia route in early February. After meeting up with the Atlantis on 14 February to the north-east of Mauritius, the Scheer journeyed further north-west and extended its patrols towards the east coast of Africa. Her presence in the Indian Ocean was reported on 21 February, when the British merchant vessel Canadian Cruiser signalled an ‘RRRR’ report to the Headquarters of the East Indies Station.

The arrival of the Scheer in the waters to the north of Madagascar had caught the East Indies Headquarters by surprise. Most of its close protection vessels were deployed off Kismayu in support of the East African Campaign. With the important convoy WS.5B off the coast of Mombasa, the East Indies Headquarters immediately dispatched HMS Glasgow, HMS Enterprise, HMS Hermes, HMS Capetown and HMS Emerald to investigate the reports. The Glasgow, Emerald, Hermes and Capetown were constituted as Force V – the hunting group, while Enterprise covered convoy WS.5B. A further distress signal was received from the Dutch Rantau Pandjang on 22 February at a position 280 miles from the scene of the first attack. After this report, a Walrus aircraft from HMS Glasgow spotted the Scheer travelling east-south-east. The Scheer, however, picked up the Allied radio intercepts about itself, and Krancke decided to quit the Indian Ocean promptly. By changing his course to south-south-east, Krancke was able to escape the clutches of the British warships. After rounding Cape Agulhas far to the south, the Scheer met the Kormoran (Detmers) and Nordmark at Andalusien, the secret rendezvous area. After successfully replenishing her supplies, Scheer travelled onwards to the North Atlantic and safely arrived in Bergen on 30 March 1941.[18]

Krüder left Andalusien in February. The SKL then ordered him to meet with the Komet (Eyssen) near Kerguelen Island. After coming together, the captains conferred to allocate new operational areas. The Pinguin would be active in the Arabian Strait, while the Komet would operate to the west of Australia. After the two ships had parted, the Pinguin travelled towards the Seychelles. On 24 April, it cut the trade route from India through the Mozambique Channel. The attack on the Empire Light (6,828 tons) and the Clan Buchanan (7,266 tons) exposed its presence in the area. The Headquarters of the East Indies Station forthwith dispatched the cruisers HMS Glasgow, HMS Leander and HMS Cornwall to pursue the Pinguin.

On 7 May, Pinguin attacked the tanker British Emperor (3,633 tons) to the northeast of Mombasa, which managed to successfully transmit a distress signal before sinking. This distress signal was picked up by HMS Cornwall which altered course towards the tanker’s last known location without delay. On the morning of 8 May, aircraft from HMS Cornwall sighted the Pinguin and pursued the raider. Late that afternoon, HMS Cornwall closed to within firing range of the raider. A short engagement followed. The Pinguin sank after receiving a direct hit which exploded amongst her complement of sea mines.[19] The remainder of the surface raiders hence relocated to the South Atlantic where the merchantmen pickings were superior.

In May, the Atlantis headed for the Cape-Freetown route as the SKL believed that there were only weak Allied naval forces in the area. On 14 May it sank the British Rabaul (6,809 tons). After a close shave with both the battleship HMS Nelson and the carrier HMS Eagle close to St. Helena, Atlantis sank the British Trafalgar (4,530 tons) on 24 May. Hereafter, the Atlantis operated off the South American coast. Throughout the remainder of 1941, the risks to the German raiders increased exponentially while the potential returns continued to diminish. In November during a conference with Hitler, Raeder explained that greater Allied countermeasures and the adoption of convoys had a detrimental impact on the effectiveness of German raiders. Despite this, Raeder planned to deploy a further four auxiliary cruisers in 1942 to operate against Allied shipping.[20]

In January 1942, Thor (Gumprich) sailed from Bordeaux. After unsuccessful confrontations with the South Atlantic whaling fleets, it succeeded in sinking the Greek Pagasitikos (3,942 tons) on 23 March. The episode took place approximately 1000 miles west of the Orange River mouth. Thor was then active in the South Atlantic and the Indian Ocean where she had some successes, albeit not in South African waters. In November, Thor was destroyed in the dockyard at Yokohama, Japan. Along with the tanker Uckermark and prize Leuthen, it was destroyed in an accidental explosion while being refitted.[21]

|

|

Ship |

Tonnage |

Country |

Lat/Long |

|

|

1 |

16 Mar 1942 (Doggerbank) |

Alcyone |

4,534 |

Dutch |

33⁰ 59'S; 18⁰ 03'E |

|

2 |

2 May 1942 (Doggerbank) |

Soudan |

6,677 |

Brit. |

36⁰ 10'S; 20⁰ 22'E |

|

Total Merchants Sunk |

2 |

||||

|

Total Tonnage Lost |

11,211 tons |

Table 3.2: Merchant shipping lost to sea-mines in South African waters, 1942[22]

The Doggerbank (Schneidewind) left Bordeaux in January with orders to lay mines off the South African coast. Between March and April the Doggerbank laid 155 mines off Cape Town, Cape Agulhas and in the area 60 miles south-south-east of Agulhas. These minefields claimed five victims between March and May. The Alcyone (4,534 tons) and Soudan (6,677 tons) were lost after striking these mines (see Table 3.2), while the Dalfram (4,558 tons), Mangkalihat (8,457 tons) and destroyer depot-ship HMS Hecla (10,850 tons) received some damage. In total, 11,211 tons of shipping were lost to German mines in South African waters, which amounts to a mere 0.79% of the nearly 1,406,192 tons lost to Axis mines throughout the war. The Doggerbank remained in the South Atlantic for another two months, whereafter she travelled onwards to Japan.[23]

On 13 March, the Michel (Von Ruckteschell) left Germany with orders to operate in the South Atlantic and the western Indian Ocean. It was not, however, to attack Allied shipping south of Ascension Island. After several successes off St. Helena during May, Von Ruckteschell decided to relocate to Tristan da Cunha in June where the merchant shipping pickings proved negligible. After relocating towards the Gulf of Guinea, Michel sank the Union Castle liner Gloucester Castle (8,006 tons) on 15 July. The liner had been travelling from Birkenhead to Cape Town. The following day, Michel scored a further success after sinking the tanker William F. Humphrey (7,982 tons). On 10 September she sank the American Leader (6,778 tons) 900 miles to the west of Cape Town. Two days later, the Empire Dawn (7,241 tons) was its next victim 840 miles west of Saldanha.[24] By February 1943 only Michel remained operational at sea. While en route to Japan in October, however, she was sunk by the American submarine USS Tarpon. After the sinking of the Michel, German raiders ceased to be considered a viable threat to Allied shipping for the rest of the war.

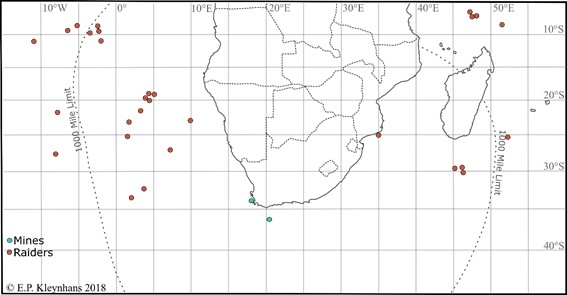

Map 3.1: Shipping lost to German raiders and mines, 1939-1942

During the war, Axis raiders accounted for 133 Allied merchantmen sunk, which amounted to an estimated 829,644 tons lost. In South African waters alone, the German raiders sunk 11 ships worth 71,012 tons – nearly 8.5% of the total tonnage lost to Axis raiders during the war (see Table 3.3). The two pocket-battleships sank a further eight merchantmen worth 47,034 tons – which constitutes 6.35% of the total tonnage lost to Axis warships during the war. During the first four years of the war, the German raiders, including warships, caused a good deal of strife and angst for the Allies, particularly in South African waters. They certainly achieved their principal objectives – that of destroying shipping, forcing the adoption of convoys, creating a harmful economic and financial situation for the Allies, and compelling the deployment of strong naval forces to protect vast sea routes.[25]

|

# |

Date Attacked On/By |

Ship |

Tonnage |

Country |

Lat/Long |

|

1 |

7 Oct 1939 (Graf Spee) |

Ashlea |

4,222 |

Brit. |

09⁰ 52'S; 03⁰ 28'W |

|

2 |

22 Oct 1939 (Graf Spee) |

Trevanion |

5,299 |

Brit. |

19⁰ 40'S; 04⁰ 02'E |

|

3 |

15 Nov 1939 (Graf Spee) |

Africa Shell |

706 |

Brit. |

24⁰ 48'S; 35⁰ 01'E |

|

4 |

2 Dec 1939 (Graf Spee) |

Doric Star |

10,086 |

Brit. |

19⁰ 10'S; 05⁰ 05'E |

|

5 |

3 Dec 1939 (Graf Spee) |

Tairoa |

7,983 |

Brit. |

21⁰ 38'S; 03⁰ 13'E |

|

6 |

3 May 1940 (Atlantis) |

Scientist |

6,199 |

Brit. |

19⁰55’S; 04⁰20’E |

|

7 |

26 Aug 1940 (Pinguin) |

Filefjell |

7,616 |

Norw. |

29⁰38’S; 45⁰11’E |

|

8 |

27 Aug 1940 (Pinguin) |

British Commander |

6,901 |

Brit. |

29⁰30’S; 46⁰06’E |

|

9 |

27 Aug 1940 (Pinguin) |

Morviken |

5,008 |

Norw. |

30⁰08’S; 46⁰15’E |

|

10 |

18 Jan 1941 (Scheer) |

Sandefjord |

8,038 |

Norw. |

11⁰S; 02⁰W |

|

11 |

20 Jan 1941 (Scheer) |

Stanpark |

5,103 |

Brit. |

09⁰00’S; 02⁰20’W |

|

12 |

20 Jan 1941 (Scheer) |

Barneveld |

5,597 |

Dutch. |

09⁰00’S; 02⁰20’W |

|

13 |

14 May 1941 (Atlantis) |

Rabaul |

6,809 |

Brit. |

19⁰26’S; 04⁰05’E |

|

14 |

24 May 1941 (Atlantis) |

Trafalgar |

4,530 |

Brit. |

25⁰17’S; 01⁰35’E |

|

15 |

23 Mar 1942 (Thor) |

Pagasitikos |

3,942 |

Greek. |

31⁰S; 01⁰W |

|

16 |

15 Jul 1942 (Michel) |

Gloucester City |

8,006 |

Brit. |

09⁰22’S; 01⁰38’E |

|

17 |

16 Jul 1942 (Michel) |

William F. Humphrey |

7,982 |

Amer. |

08⁰00’S; 01⁰00’E |

|

18 |

10 Sept 1942 (Michel) |

American Leader |

6,778 |

Amer. |

34⁰27’S; 02⁰00’E |

|

19 |

11 Sept 1942 (Michel) |

Empire Dawn |

7,241 |

Brit. |

32⁰27’S; 03⁰39’E |

|

Total Merchants Sunk |

19 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total Tonnage Lost |

118,046 tons |

||||

Table 3.3: Shipping lost to German raiders in South African waters, 1940-1942[26]

[1] The German Prize Regulations were based on the London Submarine Protocol of 1930, to which Germany subscribed in 1936. In brief, the Prize Regulations stated that German U-boats had to carry on the same stop-and-search procedure of merchant ships that surface warships had to observe. For a more detailed discussion see Keegan, Battle at sea: From man-of-war to submarine, pp. 223–224; Raeder, Grand Admiral, pp. 191, 293-295. Also see Bird, Erich Raeder.

[2] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a5/Langhammer__Erich_Raeder_1936.jpg (Accessed on 29 June 2018).

[3] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 7-9; Raeder, Grand Admiral, p. 283-288.

[4] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945.

[5] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 9-14; Raeder, Grand Admiral, p. 288-290.

[6] Throughout the war the disguised raiders bore certain operational numbers, and were referred to as such by the Kriegsmarine. The names by which they were know were, however, chosen by their respective captains. Those operational in the southern oceans were the Atlantis (Schiff 16); Orion (Schiff 36), Widder (Schiff 21), Thor (Schiff 10), Pinguin (Schiff 33), Komet (Schiff 45), Kormoran (Schiff 41), Michel (Schiff 28), Stier (Schiff 23) and Togo (Schiff 14). Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 22.

[7] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 21-23

[8] Statistical data collated from the website German Naval History, especially the individual pages dealing with the German Auxillary Cruisers during the Second World War (http://www.germannavy.de/kriegsmarine/ships/auxcruiser/index.html). Website accessed on 5 June 2017; Data verified where possible with Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 260-261.

[9] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 154-155; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 342, File: Newspaper Articles Naval War. R. Littell, ‘The Cruise of the Raider ATLANTIS´ in Readers Digest, Nov 1953, pp. 69-73.

[10] The British Admiralty introduced a number of predetermined signals to indicate when shipping was attacked. The QQQQ signal signified ‘Armed merchantman wishes to stop me’, while RRRR and SSSS signals were used to report warships and U-boats respectively. See. Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 24.

[11] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 22-27; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 342, File: Translations of Extracts from German Books. Schiff 16 (Atlantis) by Frank and Rogge.

[12] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 29; Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, p. 155.

[13] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 34

[14] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 161-163.

[15] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 342, File: Newspaper Articles Naval War. R. Littell, ‘The Cruise of the Raider ATLANTIS´ in Readers Digest, Nov 1953, pp. 69-73; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 342, File: Translations of Extracts from German Books. Schiff 16 (Atlantis) by Frank and Rogge.

[16] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 342, File: “Pinguin”. Die Kaperfahrt des Hilfskreuzers “Pinguin” 1940/41 by Dr Hans Ulrich Roll – Meteorological officer of Pinguin; Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 37-44

[17] Raeder, Grand Admiral, p. 349; Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, p. 153.

[18] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 342, File: Translations of Extracts from German Books. Das glückhafte Schiff Kreuzerfahrten des ADMIRAL SCHEER; Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 63-69.

[19] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 342, File: “Pinguin”. Die Kaperfahrt des Hilfskreuzers “Pinguin” 1940/41 by Dr Hans Ulrich Roll – Meteorological officer of Pinguin; Dimbleby, Hostilities Only, pp. 35-41.

[20] Raeder, Grand Admiral, pp. 344-367; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 342, File: Translations of Extracts from German Books. Schiff 16 (Atlantis) by Frank and Rogge.

[21] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 163-166.

[22] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945.

[23] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 22, 118-128; Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 171-172.

[24] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 144-148.

[25] Data collated and reworked from Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 22, 149

[26] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945.