THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

18)NAVAL AMBITION ANGLO S AFR

.2 Naval ambition, Anglo-South African relations, and the Seaward Defence Force

Van der Waag maintains that both the structure and organisation of South Africa’s maritime defence changed considerably at the outbreak of the Second World War. He further argues that these changes had a profound effect on Anglo-South African naval relations. At the heart of the transformation of South Africa’s maritime defence, was the formation of the SDF in September 1939. The SDF was created through the merger of the remnants of the SANS and the SANS War Reserve, as well as through volunteers from the RNVR (SA). The British, however, viewed the establishment of the SDF with much concern and regarded it as altogether unnecessary. In fact, the formation of the SDF not only marked a low-point in Anglo-South African naval relations but revealed several cracks in South Africa’s coastal and naval defences.[1]

Anglo-South African naval relations remained uneasy when, on 6 September 1939, South Africa declared war on Germany. This tension persisted despite the general euphoria surrounding the declaration of war. There was little to no cooperation between DHQ in Pretoria and the staff of the RN Africa Station in Simon’s Town. The lack of collaboration abided despite the addition of an RN Officer, Cdr James Dalgleish, to DHQ. Dalgleish’s official designation was Staff Officer (SO) SANS, and he was tasked with acting as a liaison officer in Pretoria. To the Admiralty’s advantage, the Africa Station War Order (ASWO) offered the British two strategic resources in South Africa during the war. First, the South African coastal artillery would play a key role in defending South African ports. Second, the RNVR (SA) was crucial in the Admiralty’s planning for a naval war in South African waters.

The RNVR (SA) men, along with several retired RN officers living in South Africa, would coordinate shipping control and examination services at South African ports. They would also provide signallers for shore stations, man 30 minesweepers, and provide crews for four armed merchant cruisers equipped in South Africa. Together they formed the first line of Britain’s naval defence in South Africa. The ASWO, redrafted as early as February 1939 by the office of the newly created C-in-C South Atlantic Station, VAdm George D’Oyly Lyon, furthermore guaranteed complete British control over all naval assets in South Africa in the event of war. These naval assets then reverted to the operational and administrative control of the C-in-C or the Senior Naval Officer South Atlantic. In addition, the ASWO undermined South Africa’s role regarding naval and coastal defence. The SANS was thus left with the trivial task of overseeing administrative and liaison arrangements.[2]

Fig 2.2: Vice Admiral (Sir) George D’Oyly Lyon – C-in-C Africa Station (1938-1939)[3]

By mid-1939, the RN had started preparations for a possible naval war. In the event of war, only a few RN cruisers and armed merchant cruisers – chiefly manned by RNVR (SA) personnel – would operate in South African waters. When Lyon left to administer the South Atlantic Station in Freetown in June 1939, Capt Charles Stuart RN assumed complete responsibility for the activation of the ASWO when war broke out. As the Senior Naval Officer in Simon’s Town, Stuart was at the centre of Anglo-South African relations. He was in a tricky position. He had to fulfil his wartime duties to the Admiralty, while staying in the good books of the South African General Staff.[4] Underpinning Stuart’s precarious position were fears expressed by the Admiralty before the outbreak of war. First, the Admiralty remained concerned about Hertzog’s and Pirow’s anti-British, and increasingly pro-German, attitude in the years preceding the outbreak of the war. The South African government continued to remain indifferent to the requirements of the ASWO, leaving the British rather in doubt as to what might transpire in the event of naval mobilisation in South Africa. Nevertheless, Lyon chose to circumvent the South African authorities in the event of war and mobilise the RNVR (SA) regardless.

Second, the Erebus scheme had become a point of contention by March 1939 as matters over the control of the naval reserves had come to the fore. The key to the problem was the question of manning the monitor, especially since DHQ demanded that South Africans operate the vessel. The Admiralty Staff in Simon’s Town were naturally concerned since they feared that if RNVR (SA) personnel would serve on board the HMS Erebus, its reserve pool of trained officers and men would dwindle.[5]

The third and most pressing concern on the British side was elicited by an announcement made by South Africa in August 1939. At the heart of this announcement – which was to re-establish a South African naval asset – was South Africa’s insistence on controlling its maritime defences. The Director of Coast Defence, Col H.T. Newman, would assume complete control over all Local Seaward Defences, and develop a new South African naval organisation. By the end of August, DHQ decided to establish an Active Citizen Force unit called the South African Local Seaward Defence Corps. The Corps would materialise in addition to the RNVR (SA), and had the sole purpose of providing the required personnel for M/S and A/S duties as well as administering the local examination services. This signalled the re-birth of a South African-controlled naval force, and the Admiralty was naturally concerned, particularly since these duties were the responsibility of the RNVR (SA). The effects of the reestablishment of a South African naval force were drastic.

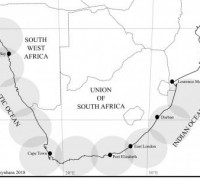

Within a week, Van Ryneveld ordered Newman to assume complete control over all South African coastal defence matters. These comprised of all of the military, air and naval measures crucial to the protection of the Union’s harbours, as well as extensive coast and the vital shipping lanes rounding the Cape of Good Hope. The naval measures also included the provision and operation of M/S and A/S patrols, shipping control service, war and port signal stations, contraband control service, examination service and the provision of A/S defences.[6]

Van der Waag accurately points out that a situation marked by duality arose at the outbreak of the war. While the RN had the use of Simon’s Town from which to project offensive power, the UDF took complete control of the overall defence of the South African ports and territorial waters. The apparent duality held serious misgivings for the already tense Anglo-South African naval relations, particularly with regard to command and control. The crucial factor sustaining this conundrum was that Newman issued direct instructions to Dalgleish. He did so without any reference to Stuart in Simon’s Town, even though Dalgleish was only detached to DHQ as an SO from the RN Africa Station. South African naval politics, it appears, were, certainly rather complex during the late 1930s.[7]

As a result of the dire state of naval affairs in the country, the outright implementation of the ASWO was recommended. The South African naval reserves were accordingly unofficially mobilised upon the British declaration of war on 3 September. The question over who actually controlled the naval forces soon came to the fore, and on 5 September, Stuart approached Van Ryneveld in this regard. The British had hoped that the timely departure of Pirow would ease defence relations. However, the status quo remained. Van Ryneveld duly informed Stuart that the Smuts Government demanded complete control over local seaward defences, since it was the only way in which South Africa could ensure the protection of her harbours. Unsurprisingly, DHQ realised it needed British cooperation in this regard, and Van Ryneveld immediately requested Stuart’s assistance.[8] Stuart promised his unwavering support in terms of naval matters. He did, however, remind the South Africans that though the RNVR (SA) had not been mobilised at the outbreak of war, the ASWO, once activated, placed the war organisation of all naval forces and harbour defence organisations on a war footing. In practise, this meant that these would revert to British control. In separate correspondence with the Admiralty, Stuart was somewhat more blunt. He warned that the naval mobilisation in South Africa was under threat. He maintained that Smuts was key to this debacle, as Smuts was highly unlikely to authorise the mobilisation of the RNVR (SA) or allow RN officers to exercise command over South African harbours.[9]

The South African naval forces were mobilised on 8 September, and RAdm Guy Halifax, a retired RN officer, assumed command of the defunct SANS and the RNVR (SA) in his capacity as Deputy Director Coast Defence. Newman next met with Stuart to convey a South African compromise proposal regarding naval and coastal defence. The Union Government, in an effort to avoid a political backlash from the nationalists, and for Smuts to be able to go to war as intended, suggested that the naval mobilising officers at each of the South African ports be appointed as officers in the SANS.[10] These officers were, however, still under the effective command of Stuart, and DHQ instructed Halifax to cooperate closely with Stuart on all matters relating to naval defence. For Stuart the situation proved problematic, especially relating to the division of command and considering the overall inexperience of the South African General Staff. Nevertheless, Stuart agreed to cooperate with the South Africans despite his reservations, and in principle agreed with Halifax on the suggested compromise.[11]

The compromise, however, needed Admiralty approval, and had serious ramifications. One of the main consequences was that RNVR (SA) personnel could no longer serve outside South African territorial waters, as the South African Defence Act specifically precluded it. The immediate effect was that no RNVR (SA) personnel could serve on RN armed merchant cruisers unless they volunteered for such service. Surprisingly, the Admiralty yielded. They did so despite the fact that Van Ryneveld created a new dilemma by ordering the amendment of the Regulations of the RNVR (SA) on 12 September to provide for complete South African control.[12]

Despite the South African insistence on taking control over its own naval and coastal defences, the mobilising of the RNVR (SA) proved problematic. Since the South African Defence Act bound the RNVR (SA) to the RN, it needed amendment. Such an amendment could only be authorised by the Union Parliament, though Smuts and his cabinet wished to keep the matter sub rosa. As a result, the mobilisation of the RNVR (SA) stalled, and South Africa was made to rely on volunteers to help operate its naval and coastal defences. Stuart, regarded the state of affairs as chaotic, and throughout September, relations between DHQ and Simon’s Town continued to deteriorate alarmingly.[13] While Stuart’s frustration at the status quo is understandable, he made matters worse by appointing several sea transport officers at Cape Town and Durban without consulting Pretoria. By October, matters had still not improved, and despite Newman’s and Halifax‘s visits to DHQ to rectify matters, the compromise system was yet to be officially implemented. Politically, the situation remained fraught. Even though the Dominion Office and the British High Commissioner, Sir William Clark intervened, the Admiralty had to remind Stuart of the importance of fully cooperating with the South African authorities and maintaining the status quo.[14]

On 19 October, a fresh set of proposals for cooperation were discussed. The discussions took place between Halifax, the South African Director General of Operations, Col Pieter de Waal, and Stuart. Following this meeting, Smuts informed Clark that South Africa would take complete ownership of the defence of its harbours and coastline. He also stated that the SDF had been created for the specific purpose of operating and manning the M/S and A/S vessels, the examination service, the coast watching service, as well as the boom and other harbour defences.

The SDF was then formed as a new Active Citizen Force unit. This occurred when the SA Local Defence Corps, the remnants of the SANS, the SANS War Reserve and volunteers from the RNVR were absorbed into it. As noted earlier, Halifax was assigned to command the SDF and carried the official designation of Director of Seaward Defence.[15] According to Stuart, this appointment signalled the effective end of the RNVR in South Africa. The SANS and SANS War Reserve where thus integrated into the SDF without the cancellation of existing arrangements with the RN. This meant that Stuart, somewhat contentiously, would be obliged to find staff from the Africa Station and avail them to train the new force. Stuart regarded the whole undertaking as a waste of time, especially in view of the lack of cooperation from and inactivity within the UDF. The Admiralty, however, continued to stress the importance of cooperation with the South Africans in the naval sphere. As a result, the Admiralty had no other option but to recall Stuart, as he was the single most decisive obstacle standing in the way of the naval compromise.[16]

In December 1939, the Admiralty evinced their formal readiness to cooperate with the functioning and training of the SDF. The only caveat was that the seaward defence of Simon’s Town remained firmly under British control. According to van der Waag, the Admiralty had reason to be satisfied. This was because the RNVR (SA) continued as before and personnel from the RNVR would only be seconded to the SDF on a temporary basis for training purposes. Moreover, the Admiralty maintained complete control over all M/S and A/S work and the shipping control service at Simon’s Town.

The SDF formally commenced its duties with regard to the coastal and naval defence of South Africa on 15 January 1940, though the retroactive establishment of the unit dated back to 1 September 1939.238 South Africa could claim something of a political victory in the whole matter. It hence assumed far greater responsibility regarding its own naval and coastal defence. These newfound responsibilities would severely tax, and test, the nascent SDF throughout the naval war in South African waters.

[1] Van der Waag, ‘The Thin Edge of the Wedge’, pp. 427-429.

[2] Van der Waag, ‘The Thin Edge of the Wedge’, pp. 432-434. Also see Spong, Osborne and Grover, Armed Merchant Cruisers 1878-1945.

[3] https://www.gettyimages.ca/detail/news-photo/vice-admiral-sir-george-hamilton-doyly-lyonthe-new-news-photo/825514940#/vice-admiral-sir-george-hamilton-doyly-lyon-the-newcommanderinchief-picture-id825514940 (Accessed on 29 June 2018).

[4] Van der Waag, A Military History of Modern South Africa, p.187; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 240, File 215: Union Coast Defences. South African Naval Forces, 15 Aug 1940.

[5] Van der Waag, ‘The Thin Edge of the Wedge’, pp. 434-436; Visser, ‘Anglo-South African Relations and the Erebus Scheme’, pp. 68-98.

[6] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 86, File: MS 11. Coast Defence Policy, undated; DOD Archives, CGS, Group 2, File: CGS/367/13/9. DCGS to Director of Training and Operations, 3 Aug 1939. Also see Bisset, ‘Coast Artillery in South Africa’, pp. 333-357.

[7] Van der Waag, ‘The Thin Edge of the Wedge’, pp. 434-436.

[8] TNA, Admiralty Papers (ADM) 116/4344. SNO to Admiralty, 3 Sept 1939; TNA, ADM 116/4344. SNO to Admiralty, 6-7 Sept 1939.

[9] Van der Waag, ‘The Thin Edge of the Wedge’, pp. 436-437.

[10] Potgieter, ‘Maritime Defence and the South African Navy’, p. 169; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 240, File 215: Union Coast Defences. South African Naval Forces, 15 Aug 1940.

[11] TNA, ADM 116/4344. SNO to Admiralty, 9 Sept 1939.

[12] Van der Waag, ‘The Thin Edge of the Wedge’, pp. 438-439.

[13] TNA, ADM 116/4344. SNO to Admiralty, 21 Sept 1939; TNA, ADM 116/4344. SNO to Admiralty, 13 Sept 1939; DOD Archives, Secretary for Defence (DC), Box 1973, File: DC 396/38. SNO to Secretary for Defence, 28 Sept 1939; DOD Archives, DC, Box 1973, File: DC 396/38. Secretary for Defence to SNO, 30 Sept 1939.

[14] Van der Waag, ‘The Thin Edge of the Wedge’, pp. 439-441.

[15] Potgieter, ‘Maritime Defence and the South African Navy’, p. 169.

[16] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 240, File 215: Union Coast Defences. South African Naval Forces, 15 Aug 1940; Van der Waag, ‘The Thin Edge of the Wedge’, pp. 441-443. 238 Van der Waag, ‘The Thin Edge of the Wedge’, p. 443.