THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

16)CONTROL VICTUALLING AND REPAIR

1.4 The control, victualling, and repair of Allied shipping in South Africa

The South African harbours were not duly strained at the outbreak of the war. The Union authorities did realise though, that as the war progressed, Union ports would increase in strategic value. This would result in an inevitable rise in the presence of Allied naval vessels, troop transports and merchant shipping calling at these ports. As follows, the SAR&H implemented a host of development plans to provide additional facilities in anticipation of the greater use of South African ports. This farsighted policy by the Union authorities was justified by 1940. Following the Italian entry into the war and the closure of the Mediterranean, a large number of Allied merchants and naval vessels were forced to make use of the strategic shipping lane around the Cape of Good Hope (see Graph 1.7). The Japanese invasion of the East Indies and Burma, as well as Japan’s occupation of Singapore and Hong Kong, only added to the complications. South African waters at once became a vital link in the main Allied supply routes to and from the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent and the Far East. The Union ports also provided vital anchorage, victualling, dry-docking and repair facilities to the visiting naval and merchant vessels.[1]

.jpg)

Graph 1.7: Total number of Allied naval vessels that called at the major South African ports, 1939-1945[2]

Along with the provision of a key connection between Allied supply routes, the South African harbours acted as the lifeline of the Union. The best part of the Union exports and imports passed through its ports at one stage or another. This turn of events naturally placed additional strain on the control measures and infrastructure of the SAR&H since 1940.

At the outbreak of the war, most South African ports were considered inadequate to handle existing peacetime merchant traffic, despite upgrades in some harbours. South Africa was, however, fortunate that actual hostilities did not extend to any of its territories. Neither the Ossewabrandwag nor other Axis elements succeeded in destroying any of the SAR&H harbour facilities during the war, despite several attempts at sabotage by the former.[3]

Fig 1.5: The return of the 1st South African Division from North Africa, 1943[4]

Although the war placed severe pressure on South African manpower and materials, the development of the harbours continued unabated to ensure the speedy turn-around of shipping in South African ports. Pre-war development plans for SAR&H harbours, which included the provision of additional sheds, cranes and cargo-handling facilities did, however, have to be abandoned. The highest priority was given to essential work for the maintenance and expansion of vital harbour services. During the first few years of the war, inadequate use was made of the Port Elizabeth and East London harbours to relieve shipping congestion at Cape Town and Durban.[5] Before these harbours became viable and offered a quicker turn-around time, adequate oil storage had to be constructed, and sufficient coal-bunkering and repair facilities established. Some of the most notable developments took place in Cape Town, Durban and East London. Cape Town harbour saw the construction of the Sturrock and Duncan Docks and at East London the Princess Elizabeth Graving Dock was built. At Durban, the Maydon Channel was widened and deepened, the general Maydon Wharf, Point Area and Salisbury Island upgraded, and a Royal Air Force Flying Boat Base established.[6]

Fig 1.6: The official opening of the Duncan Dock at Cape Town Harbour, 1943[7]

The suspension of airmail services and the irregularity of surface mail added a further dimension to the shipping predicament in South African harbours. This meant that ships often arrived ahead of the copies of their manifests or bills of lading, which naturally created delays in the handling and clearing of accumulated cargo at SAR&H sheds and along the wharves. The diversion of shipping from one South African port to another was also complicated, especially since the South African authorities had to match ship arrivals with an adequate number of rolling stock at each port. The system was complicated as long hauls marked the South African railway system and rolling stock, as a rule, remained scarce.

Many of the merchant vessels which called at South African ports were, furthermore, bound for other destinations, and the cargo they brought to the Union was merely the result of topping up. These merchant ships invariably formed part of convoys which amassed in Union ports before continuing on their outward journeys.

This congestion proved a nightmare for the South African authorities. Not only did all of these vessels have to be accommodated, bunkered, watered, and replenished with logistical stores, a high proportion of them needed repairs. A further frustration experienced was that of procuring sufficient ships’ stores. This was partly because the priority ratings afforded to the import of ships’ stores by South African handlers in Britain and North America were too low to ensure that they obtained the required supplies posthaste. Given the strategic situation this was rather unreasonable, as the quick turnaround of naval and merchant vessels calling at South African ports remained imperative.[8]

It took the South African authorities a considerable amount of time to come up with adequate solutions to all of the shipping related problems within its sphere of influence. To start with, the Merchant Shipping Control Committee (MSCC) was established on 7 December 1939. The objective of the MSCC was to cooperate with the Union representative of the British Ministry of Shipping, the forerunner of the MWT. Their combined efforts would result in controling the supply of coal and oil for use as fuel in vessels and the use of South African harbours for docking and repairs. It would also enforce discipline amongst merchant crews and coordinate the supply of ships’ stores. Later on, the MSCC relinquished some of its responsibilities to other South African authorities.[9]

Fig 1.7: HMS Illustrious calling at Cape Town during the war[10]

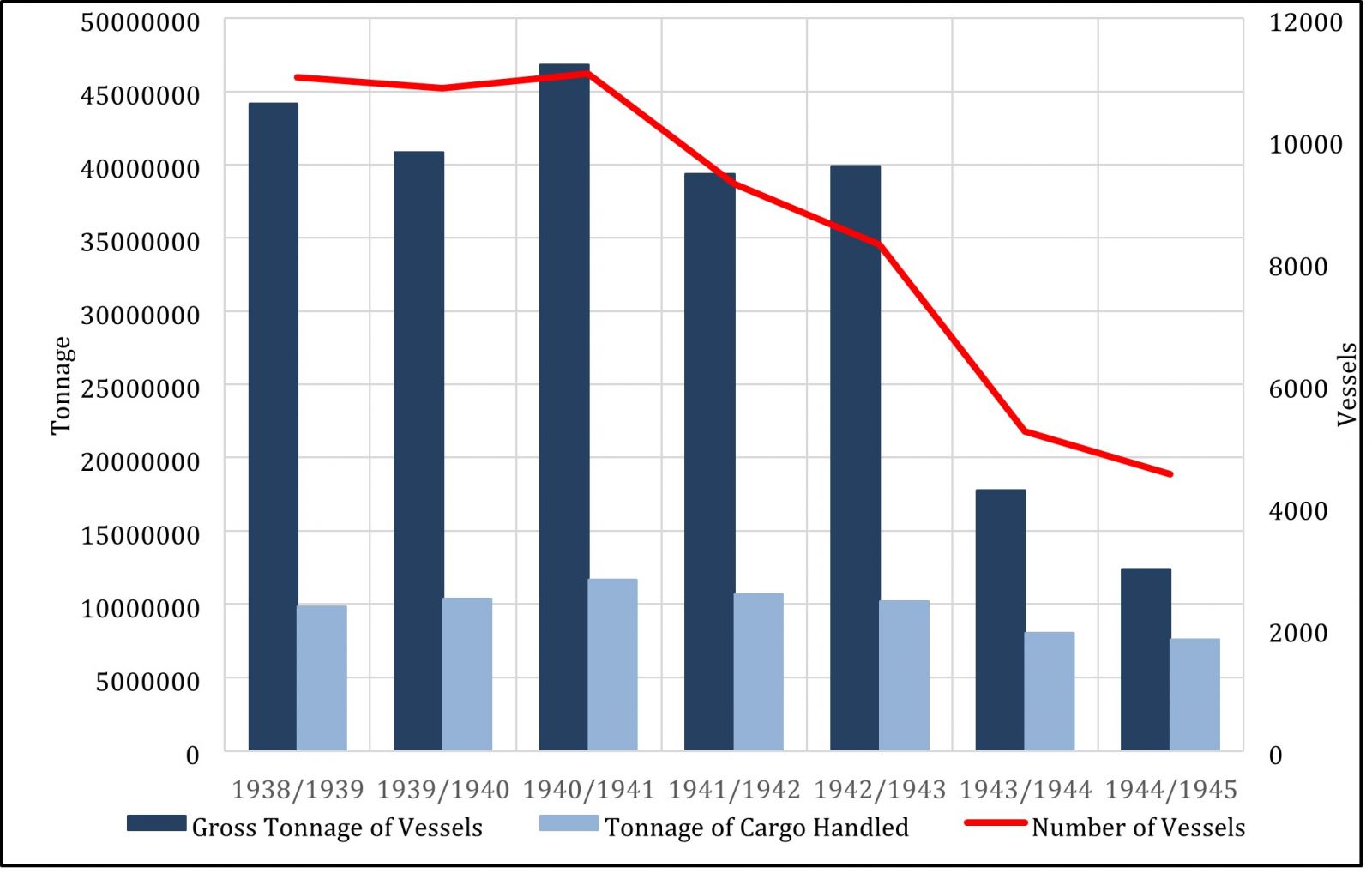

The Union harbours were the most taxed during the 1940/1941 fiscal year, especially after the closure of the Meditteranean to shipping, when the total number of merchant vessels that passed through South African waters reached record figures for the war. During this period, 11,082 merchant vessels, comprising 46,831,026 gross registered tons, called at South African ports. An accompanying total of 11,652,522 tons of cargo additionally passed through South African ports during this timespan, with a record figure of 5.5 million tons of cargo landed (see Graph 1.8).[11]

Graph 1.8: Fluctuations in the handling of vessels and cargo at South African and South West African ports, 1939-1945[12]

It soon became imperative to appoint senior officials from the SAR&H to act as port directors at Cape Town and Durban. The functions of these Port Directors varied. They had to represent the Government, through the Minister of Railways and Harbours, in respect of administrative questions arising in connection with the administration and functioning of ports and shipping. They were expected to coordinate the activities of the civil and military departments at the respective ports, as well as coordinate their relations with the commercial community. They had full powers to act on behalf of the Government, except where important points of policy were concerned.[13] The Port Directors also had the power to investigate, where necessary, items brought to their attention where the opinion was that improvements at the ports could be affected. When the supply of ships’ stores became critical, partly due to importing difficulties, the Port Directors took the responsibility of certifying and expediting all applications for import permits, and to ascertain that such stores remained in bond and not cleared for other purposes. The appointment of Directors at Durban and Cape Town met with considerable success in the coordination of the efforts and activities of the naval, military and civilian authorities. Their assingment also allowed for closer contact with the representatives of the MWT and the WSA. The results were so satisfactory that it was decided to extend the powers of the Directors at Durban and Cape Town to encompass the ports of East London and Port Elizabeth.[14]

By the middle of 1942, the offensive operations conducted by enemy submarines along the South African coast intensified and became an increasing menace to Allied shipping in the Southern Oceans. These operations, coupled with the somewhat heavy toll taken by Allied shipping as from October 1942, necessitated the Union Government to speed up the turnaround of merchant vessels visiting its ports. These operations also prompted the British Admiralty and the South African Naval Forces (SANF) to speed up and intensify its anti-submarine warfare measures. The SANF was tasked with provision of the safe conduct of merchant vessels along the South African coast. [15]

The MWT, in consensus with the Union Government, appointed a commission by mid-1942. Headed by R.B. Tollerton and C.E. Wurtzburg, the objective of the commission was to make an exhaustive analysis of the status of shipping in South African waters. One of the main points considered by the commission was the overbearing need for the quick turn-round of merchant shipping in South African harbours. The commission recommended the establishment of an organisation that could obtain accurate and advance information regarding all shipping under British control approaching South Africa, as well as their respective ports of call, specific logistical requirements, and expected times of arrival in port. This organisation would also have the power to divert shipping to appropriate anchorages when needed. In short, the commission would have the power to divert shipping, but would not have enough power to interfere with the day-to-day operation or control of the harbours operated by the SAR&H. The MWT made representations to the WSA, who duly agreed to cooperate in the functioning of this recommended organisation.[16]

The South African Ports Allocation Executive (SAPEX), sanctioned by the Union Minister of Transport, was created on 1 January 1943. It promptly took over the responsibility of combatting the long turn-around time of shipping in South African harbours.[17] VAdm (Sir) Campbell Tait, Commander-in-Chief of the South Atlantic Station, and the chief representative of the MWT in South Africa came to an agreement that Cape Town should became the headquarters of SAPEX. The Cape Town Port Director also acted as the Chairman of SAPEX

.

Fig 1.8: Vice Admiral (Sir) Campbell Tait – C-in-C South Atlantic Station (1942-1944)[18]

The SAPEX committee comprised of representatives of the SAR&H, the MWT, the WSA, the RN, the SANF and the Union Controller of Ship Repairs. The committee, which sat daily in Cape Town, received advance information of all shipping approaching South African waters. This information included their cargo manifests and ultimate destination, along with their bunkering, stores and repair needs. The data gathering was made possible through the use of a universal form used by all ports of despatch across the globe. These were supplemented by VELOX and VESCA messages[19] received through naval channels, that provided all the essential information needed without putting a strain on the already heavily taxed cabling facilities. The committee was, however, constantly aware of the security risks associated with the daily transmission of such shipping information, and took all possible means to prevent the leakage of shipping information to enemy agents.182

The SAR&H also provided SAPEX with additional findings. These included the daily returns of all the shipping in South African harbours; the amount of cargo being loaded and discharged and the amount of coal or oil being bunkered. Further information entailed whether water and stores were being taken on; whether repairs were being done – with estimates of when each of these would be completed – and when the ship would be ready to sail. SAPEX was required to take into account the different harbour facilities for handling ships and cargo, along with the availability of rail connections and escorts by surface ships and aircraft, as well as the impact of delays on group sailings. Such information allowed SAPEX to order merchant shipping to the most suitable ports in each situation. Customs officers and port authorities would accordingly be alerted, crew’s mail redirected, and cargo manifests and other documents forwarded to the various ports concerned.183

The question of final delivery, however, remained contentious for SAPEX, as it was essentially the concern of each shipping line. After the matter was referred to the MWT and the WSA, the various shipping lines were instructed to make out all Bills of Lading for cargo shipped to South African ports for a named port, or any other port in South Africa, as directed by SAPEX. The commission made a further effort to spread the load of imported traffic over the four main South African ports. It did so by recommending that the Allied exporting countries should load their cargo for discharge at each of the four main Union ports. Along with the Canadian authorities, the MWT readily accepted the proposal. The single caveat was that there be no unnecessary delay in cargo handling. The United States authorities did not welcome the suggestion at first. They did, however, subsequently agree to a three port loading scheme – also with the provision that there be no delay in the despatch of American ships.184

centres and additional reporting officers to permit a reasonably accurate plot of all merchant shipping world-wide. This system was called the "VESCA" (Vessel and Cargo) system. The VELOX messaging system allowed for confidential shipping information to pass between ports and the Reporting Officers in the Cape Intelligence Area. The VELOX telegrams was essentially a coded and re-coded message and comprised the VELOX message in plain language, the ship’s signal letter along with a dummy letter, the estimated time of arrival, and the time of origin and date in plain language. See US Navy Department, History of Convoy and Routing, p. 63.

- DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 24, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII. Ports & Shipping.

- Martin and Orpen, South Africa at War, p. 136.

- DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 24, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII. Ports & Shipping.

An off-shoot of this redistribution of shipping arrivals amongst South African ports, was the establishment of Saldanha Bay as a defended lay-by anchorage.[20] Saldanha is South Africa’s only natural protected anchorage. Even so, it lacked an adequate supply of water and harbour facilities, which prevented it from handling a large number of ships at any one time. From 1942 the South African authorities attempted to rectify this position. Initially, fresh water was conveyed from Cape Town by a water-tanker on a temporary basis. Lighters and temporary bunker facilities were conversely available on a more permanent basis. The harbour at Saldanha, also underwent several key developments. Among these were the installation of a pipeline from the Berg River to supply 1 million gallons of water per day, a reinforced concrete jetty, a ship-repair depot and oil storage tanks. Unfortunately, most of these projects only reached completion after the port’s greatest need had passed.[21]

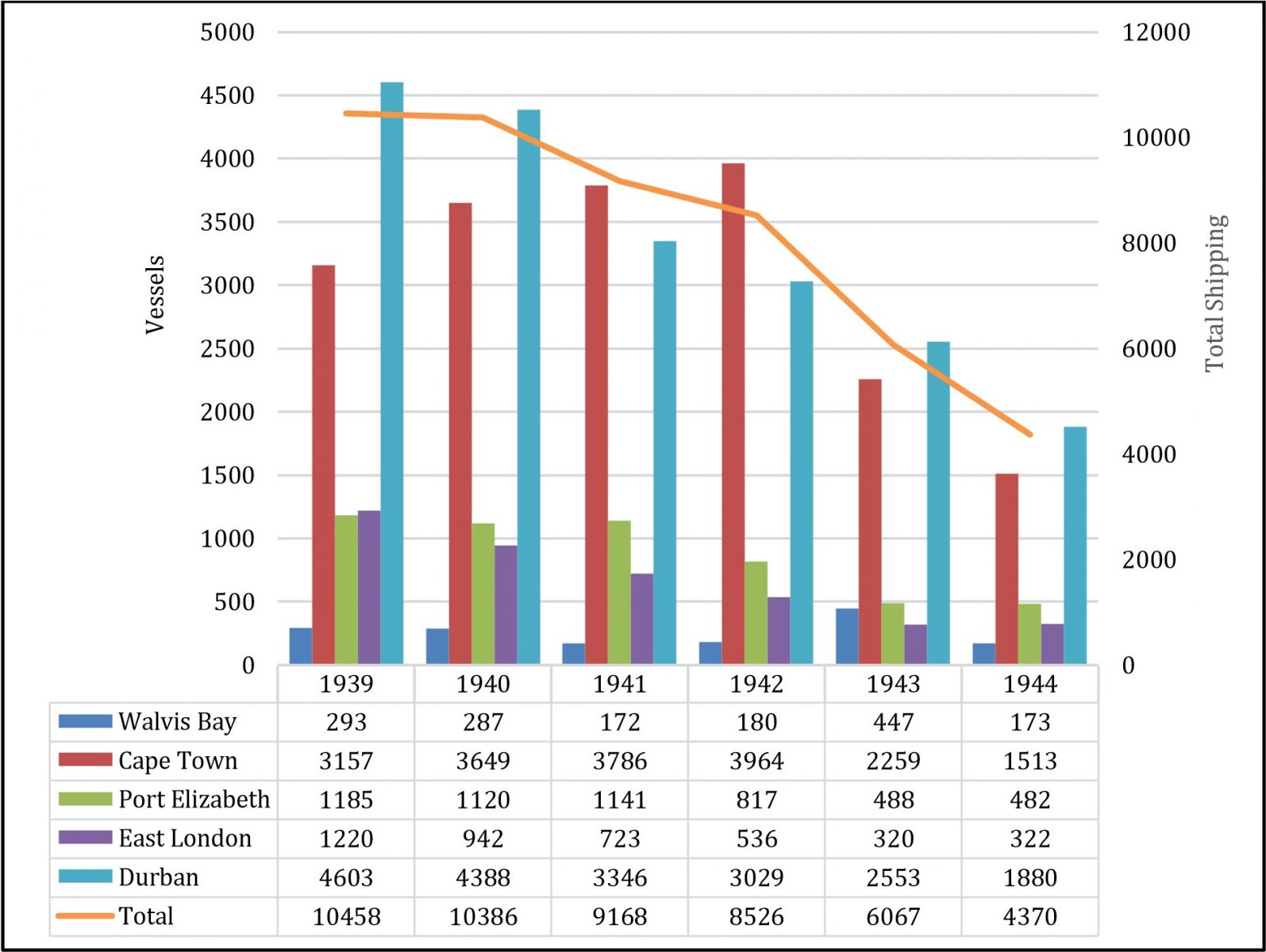

Graph 1.9: Total merchant shipping handled at South African ports, 1939-1944[22]

By early 1943 there was a drastic change in the war situation. The Allied success in North Africa and the opening of the Mediterranean shipping route meant that far fewer Allied naval vessels and merchantmen would use the strategic shipping lanes around the Cape of Good Hope. This had a dramatic effect on the South African shipping position, with a drastic decline in the volume of shipping calling at Union ports for the remainder of the war (see Graph 1.9). Despite this reduction in shipping, the tonnages of imported cargo handled at South African ports remained fairly constant. The Cape Town and Durban ports remained particularly busy owing to an increasing demand for South African exports. Throughout the war, the combined efforts of the SAR&H, MSCC, SAPEX, MWT and WSA ensured the quick turn-around of both the Allied merchant shipping and naval vessels which called at South African ports.188

Before the outbreak of the war, ship repairs in South Africa consisted mainly of minor overhauling of merchant vessels and the maintenance of fishing trawlers and whalers. Only two ports possessed graving docks, with nearly 150 men employed between them. By 1941, following the closure of the Mediterranean to Allied shipping in 1940, nearly 60% of the merchant and naval shipping that rounded the Cape of Good Hope required repairs. This demand necessitated major repairs and overhauls to be facilitated at South African harbours.189

On 31 January 1941, a Director of Merchant Ship Repairs was appointed to decide on the priority of repair work and its allocation. The Director of Merchant Ship Repairs further allocated repair work between various firms on a cost-plus pricing basis, which seemed the only feasible method. Unfortunately, the cost-plus pricing basis did not furnish a strong incentive on the firms to complete the work in the shortest possible time. Both the RN and SDF, however, allocated their own repair work, which received priority above the Allied merchants. This division between authorities naturally led to some challenges. By September 1941 a Controller of Ship Repairs was appointed with authority to decide on all priority repairs, and direct all shipping repair work in the Union. He also had a seat on SAPEX, and gave valuable advice to this committee, especially on the completion dates of vessel repairs. The Controller of Ship Repairs further centralised the supplies used in shipping reconditioning into the Merchant Shipping Repair Pool, upon which contractors could draw as the need arose. In addition, his office was responsible for the procurement and importation of the overseas material needed to undertake shipping repairs. The appointment of Deputy during the war is incomplete, though there was a definite surge in merchant vessels visiting the port from the latter half of 1942 to mid-1943.

- DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 73, File: Year Book, Section XI. Shipping.

- DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 23, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII – Addenda to Volumes I and II Ports and Shipping. Memorandum on the Ship Repair Organisation; Martin and Orpen, South Africa at War, pp. 136-137.

Controllers at each of the principal South African ports assisted the Controller of Ship Repairs in the execution of his duties.[23]

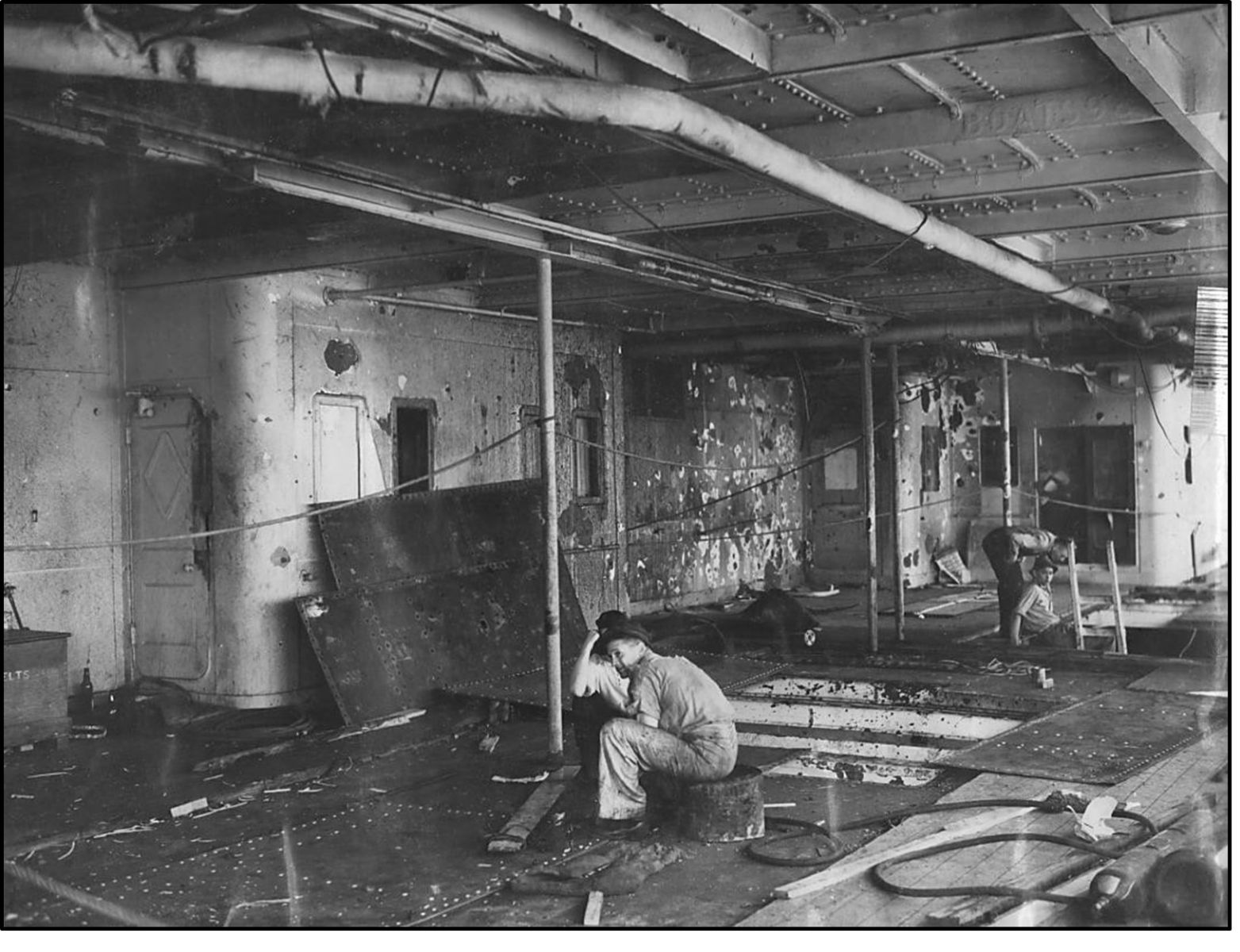

Fig 1.9: Naval repair work undertaken at a South African port during the war[24]

Graving dock space, however, remained very limited, and by the middle of 1942, as many as 78 ships lay idle outside South African harbours awaiting repairs. This episode was largely due to the loss of docking facilities in the Middle and Far East, which especially confirmed the strategic importance of the Durban graving dock. A further imminent matter was the acute shortage of skilled labour. The scarcity of skilled workers was largely a result of artisans being transferred from the Witwatersrand against their liking. The resultant state of affairs occurred at the expense of the crucial munitions and engineering industries vital to the South African war economy.

At the height of the shipping repair work period, nearly 1,300 men were employed at Durban, 932 men at Cape Town, 204 men at Port Elizabeth and a further 135 men in East London.[25] Despite the above-mentioned pitfalls, the number of ships repaired in South African ports was considerable. The weekly average of ships repaired from March 1941 to March 1943 totalled sixty-two. A number of vessels were repaired after being torpedoed, while some craft were converted into armed cruisers and hospital ships. Some Allied liners had their boilers completely overhauled, while repairs to naval guns were also carried out. At least 4,451 ships were fitted with degaussing equipment, and many with radar and asdic equipment. Three floating docks were built along with the production of several general launches, cutters, dinghies, lifeboats and special equipment such as Fairmile motor launches. Most of this work had never been contemplated in South Africa before the war.[26] By the end of 1943 there was a marked decline in the number of ships being repaired, especially after the Mediterranean was re-opened for naval craft. The ship repair organisation was, however, kept in readiness for the predicted Middle East offensive. By March 1944 this need no longer existed. As a result, the Ship Repair Control Organisation in South Africa was permanently closed down well before the Japanese surrender in 1945 (see Table 1.5).[27]

.jpg)

Table 1.5: Total number of ships repaired in South Africa, 1941–1944[28]

Conclusion

It is undeniable that a close study of shipping forms the basis to understanding the Axis and Allied maritime strategies in South African waters during the war, largely due to the interconnectivity of the Allied war effort particularly in the naval sphere. The availability of merchant shipping for imports and exports was crucial to the continued functioning of the South African war economy. Sourcing this shipping proved problematic, as South Africa often desired more imports than the Allied shipping programmes were able to provide. The introduction of a number of control measures, such as priority rating and the establishment of the CSAB, helped to ease South Africa’s wartime shipping dilemma. The strategic location of South Africa astride a main maritime trade route meant that large numbers of naval and merchant vessels visited its harbours as they passed round the coast during the war. South Africa evidently had to exercise control over all the vessels which visited its ports. It also had to make adequate provision for the victualling and repair of these vessels.

The establishment of SAPEX, and the appointment of the Controller of Ship Repairs, helped the South African authorities to exercise a large measure of control over the shipping situation in general. Despite its continued importance to the Allied war effort, the South African contribution with regard to shipping, remains underappreciated. The importance of the Cape Town/Freetown shipping route did, however, not go unnoticed by the OKM and SKL. They maintained that far-flung operations off the coast of South Africa were only feasible if there was sufficient sinking potential to justify a sustained U-boat offensive. It is thus rather unsurprising that the Axis and Allied maritime strategies off the South African coast during the war were reactionary rather than preventative in nature. This comes to the fore in the following chapters, where the execution of the Axis and Allied maritime strategies in South African waters are discussed at length. The first step of this discussion involves the measures taken to protect the South African coast, which are investigated in Chapter 2.

[1] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 24, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII. Ports & Shipping.

[2] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 24, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII. Ports & Shipping.

[3] NWU, RAM Div, Ossewabrandwag Archive (OB Archive), Transkripsie/Bandopname D.J.F. Scribante – Sabotasie van Durbanse Hawe.

[4] South African National Museum of Military History, Masondo Reference Library. SA Navy Photo Collection, S.A. 4491.

[5] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 73, File: Year Book, Section XI. Shipping.

[6] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 23, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII – Addenda to Volumes I and II Ports and Shipping. Port Development.

[7] South African National Museum of Military History, Masondo Reference Library. SA Navy Photo Collection, S.A. 4699.

[8] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 24, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII. Ports & Shipping.

[9] Martin and Orpen, South Africa at War, p. 136.

[10] South African National Museum of Military History, Masondo Reference Library. SA Navy Photo

Collection, S.A. 951.

[11] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 24, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII. Ports & Shipping.

[12] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 24, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII. Ports & Shipping. Stats reworked from the information contained in the document. Please note that these stats are complete, unlike those contained in Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 258 and Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 319-320.

[13] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 73, File: Year Book, Section XI. Shipping.

[14] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 24, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII. Ports & Shipping.

[15] Kleynhans, ‘Good Hunting’, pp. 173-183.

[16] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 24, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII. Ports & Shipping.

[17] Hancock and Gowing, British War Economy, p. 420; Martin and Orpen, South Africa at War, p. 136.

[18] https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/vice-admiral-sir-william-campbell-tait-18861946-175436 (Accessed 29 June 2018).

[19] After the outbreak of the war in Europe the British Admiralty once more took recourse the Lloyds reporting system, the relationship dating back nearly 200 years, and hence modified it to meet wartime needs and augment it by including reports from routing officers, intelligence

[20] Burman and Levin, The Saldanha Bay Story, pp. 145-152.

[21] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 189-195. For more on the development of Saldanha during the war see Visser and Monama, ‘Black workers, typhoid fever and the construction of the Berg River – Saldanha military water pipeline’, pp. 196-198; Visser, Jacobs and Smit, ‘Water for Saldanha’, pp. 141-143.

[22] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 24, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War

History Vol VIII. Ports & Shipping. Note that statistics on merchant shipping handled at Saldanha

[23] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 23, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII – Addenda to Volumes I and II Ports and Shipping. Establishment and Functioning of Controller of Ship Repairs; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 23, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII – Addenda to Volumes I and II Ports and Shipping. Memorandum on the Ship Repair Organisation.

[24] South African National Museum of Military History, Masondo Reference Library. SA Navy Photo

Collection, S.A. 564.

[25] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 23, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII – Addenda to Volumes I and II Ports and Shipping. Establishment and Functioning of Controller of Ship Repairs.

[26] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 25, File: Shipping Repairs. South Africa’s Achievement in Wartime Shipping Repairs; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 73, File: Year Book, Section XI. Shipping.

[27] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 23, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII – Addenda to Volumes I and II Ports and Shipping. Establishment and Functioning of Controller of Ship Repairs.

[28] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 73, File: Year Book, Section XI. Shipping; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 23, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII – Addenda to Volumes I and II Ports and Shipping. Establishment and Functioning of Controller of Ship Repairs.