THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

15)SOUTH AFRICAN ALLIED WAR EFFORT

1.3 South Africa, the Allied war effort, and the wartime shipping problem

Some of the most enduring aspects of the Second World War were the problems associated with providing adequate shipping to implement the Allied war production plans, and for the Allies to keep abreast of the ever-changing military situation. Added to this was the accompanying problem of allocating enough shipping to meet the logistical and economic requirements of the civilian populations, and to help deploy Allied manpower and war equipment over geographically removed strategic areas.

Unsurprisingly, shipping was vital to the overall Allied strategy throughout the war.[1] It is a well-established fact that a British defeat would have been inevitable during the first two years of the war, had the RN been unable to keep the vital sea trade routes which linked the island nation to the rest of the Commonwealth and the United States of America (USA) open. The continued operation of these vital trade routes formed an essential pre-condition for ultimate victory in the war. Without the continued flow of seaborne trade between the Allied nations, it would have been impossible for the Allies to mobilise to their full strengths, coordinate and maximise their industrial and productive efforts, or conduct the final offensives which brought the war to a successful end.[2] It is under these conditions that South Africa’s shipping requirements and associated problems during the war come to the fore. This aspect of the South African war effort has received little to no scholarly attention, despite its importance in understanding both the Axis and Allied maritime strategies off the Southern African coast during the war.

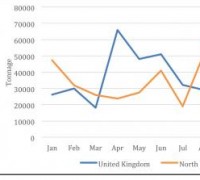

Graph 1.1: Monetary worth of South African imports and exports, 1930-1945[3]

After the declaration of war, the maintenance of the South African civilian economy warranted two actions. These were the expansion of her wartime production and the full exploitation of the country’s natural and industrial resources (see Graph 1.1). It also necessitated that the Union procure a broad range of imported supplies. Furthermore, the shipment of the Union’s exports to various global destinations, predetermined by London and later on by Washington, was required. These imports and exports were set in motion as a contribution to the Allied war effort.[4]

During the first few months of the war, the Allies did not face a serious lack of commercial vessels for the transport of goods. Despite heavy shipping losses sustained during the Battle of the Atlantic, the Allies could more than compensate for these losses. They did so through the acquisition of merchant vessels from European nations overrun by German forces, or through the creation of new construction programmes.[5] The German occupation of Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium and France in 1940 eased some of the pressure placed on the British and Allied merchant fleets. This was due to their respective merchant fleets becoming available for the Allied shipping cause.

The acessability of these merchant fleets subsequently caused several complications. While both the British and Germans naturally desired to press the majority of these merchant fleets into their service, this was no easy task. With the help of the Dominions, Britain was able to seize any such shipping that called at Commonwealth ports, thus preventing these vessels from escaping Allied control.[6] This often involved the detention of the vessels and the internment or repatriation of pro-Nazi, or reluctant masters and seamen – even in South Africa.[7] On certain occasions, vessels that were technically treated as an enemy craft, were seized as prizes of war. This was particularly the case with Vichy French shipping. Upon agreement, these ships were then either allocated to South Africa or the United Kingdom (UK) for wartime usage.[8]

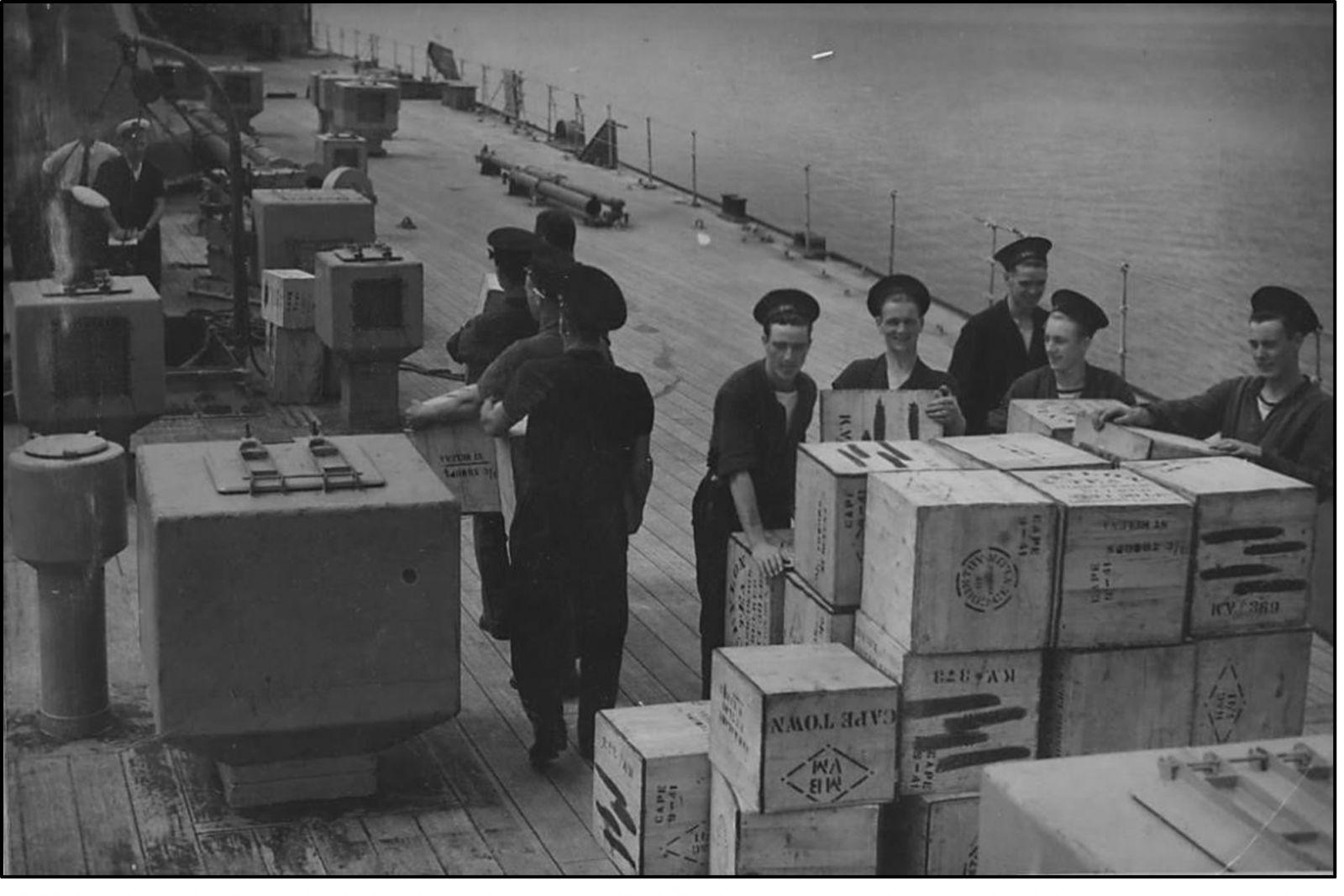

South Africa did not face any palpable difficulties of supply during this period, and the British export drive, which continued well into 1941, meant that sufficient export tonnage was earmarked to heed the Union’s every need. The shipping situation, however, soon deteriorated, especially when the Middle East, and both East and North Africa, became important theatres of military operations from around mid-1940.[9] The closure of the Mediterranean to merchant shipping after the Italian entry into the war in June 1940, and the capitulation of France in the same month placed further strain on Allied merchant shipping. The burden on the Allies was heightened by the significant number of merchantmen diverted to Russia after the commencement of Operation Barbarossa.

Fig 1.1: An Allied merchant convoy approaching Cape Town Harbour, 1940s[10]

The Japanese and American entry into the war in December 1941 further served to exacerbate the matter.[11] Their entry combined to trigger a grave shipping crisis, where the demand for shipping space vastly increased. This state of affairs held serious misgivings for South Africa, as the Union could obtain only such imports as were allocated to her through the process of combined planning overseen by the British Ministry of War Transport (MoWT).[12]

Graph 1.2: Export of principal South African products in weight, 1938-1945[13

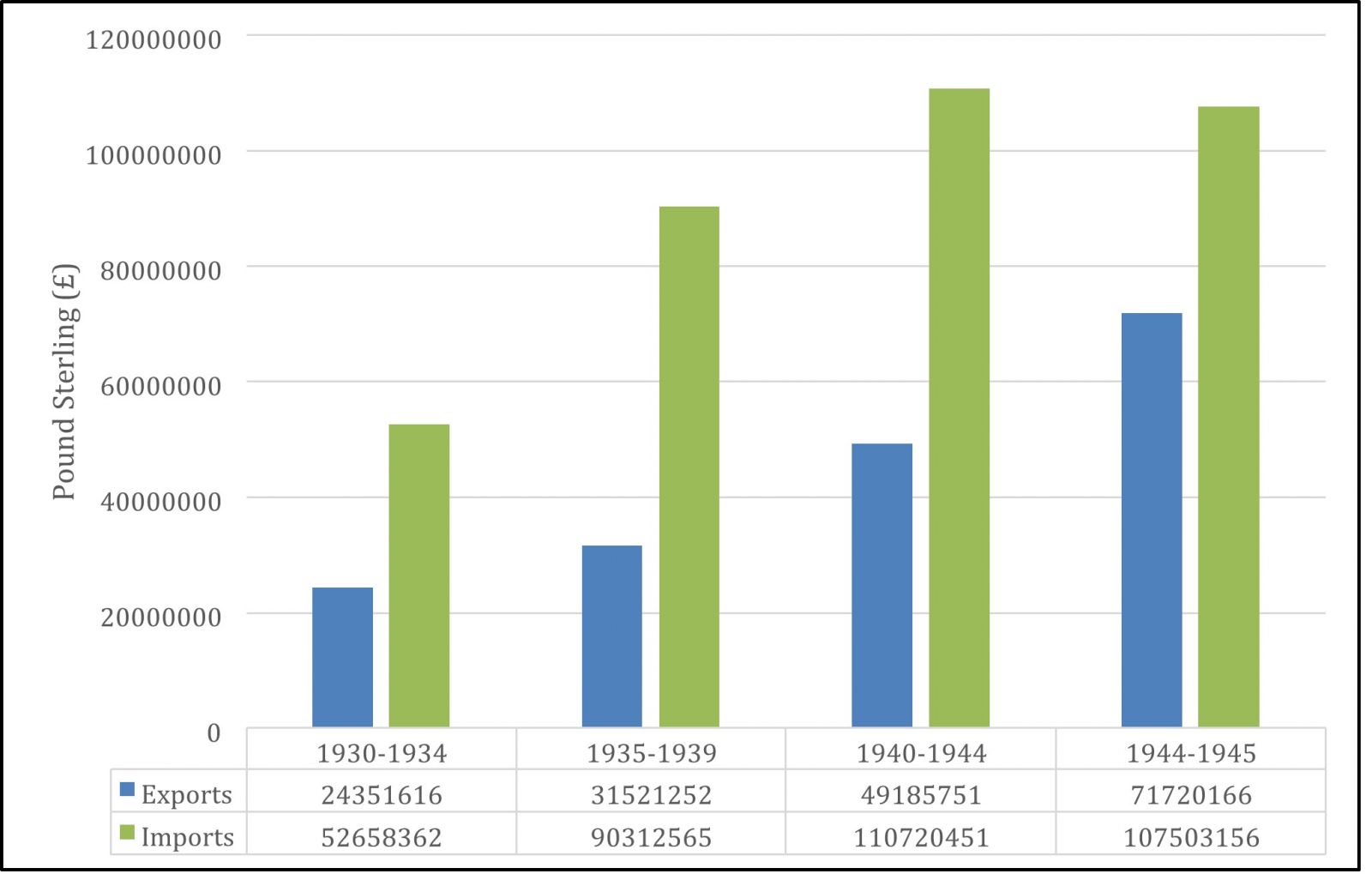

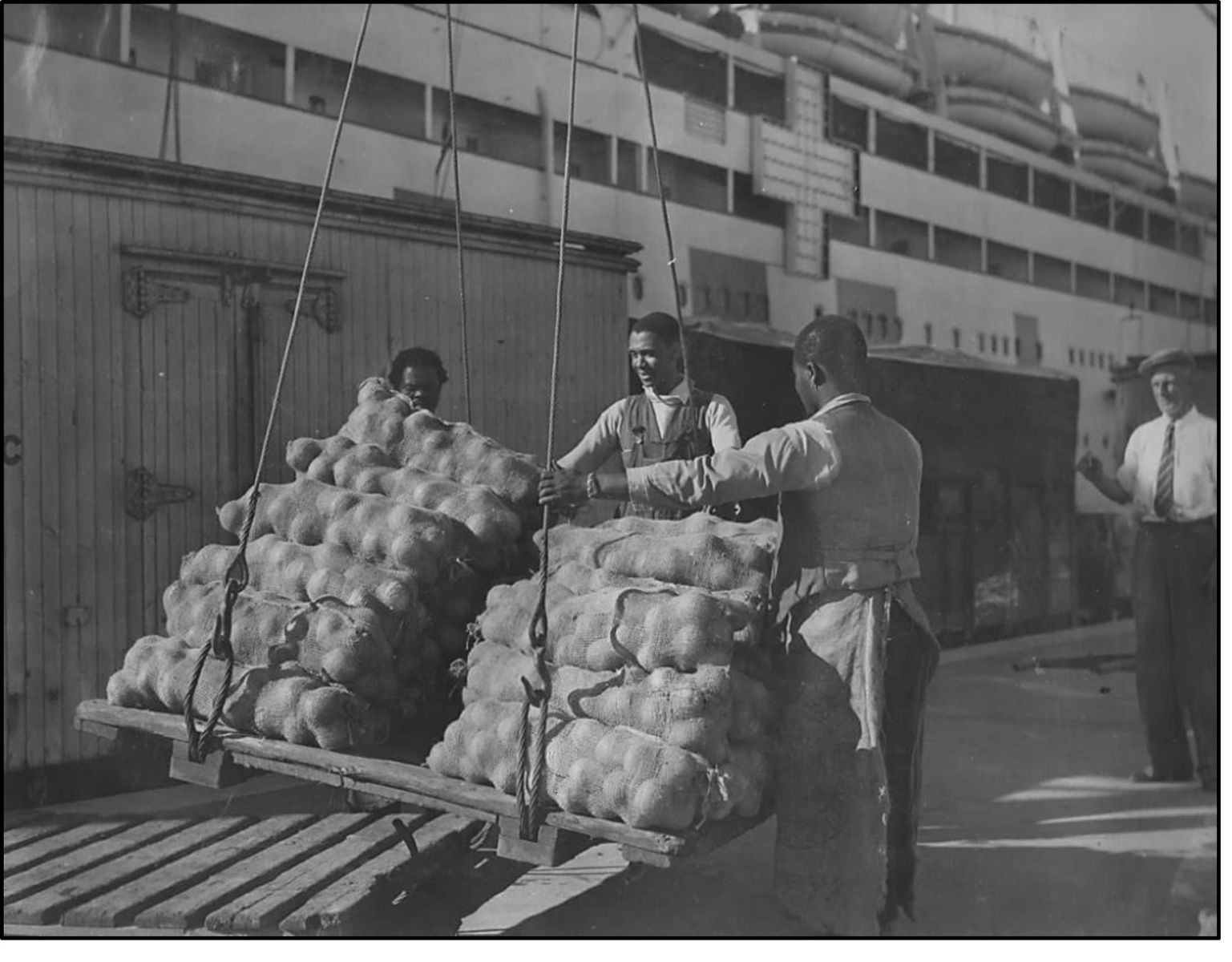

Two main problems underpinned the South African shipping problem throughout the war. The first problem related to the available freight space for imports, especially those originating from the UK, North America and the rest of the Commonwealth. The second problem dealt with the freight space needed to export South African raw materials, agricultural produce and other finished products from its various industries (see Graph 1.2). These two problems were, however, interrelated. The securing of shipping for imports was entirely dependent on the importance, and destination, of the exports. The leading South African wartime exports, chiefly coal, were destined for the Middle East and the Eastern Group Supply Council countries (see Graph 1.3).[14] Moreover, the vessels used for exports did not suffer frequent diversions. Shipping space for South African exports to the UK and the USA was considered adequate, despite a persistent shortage of refrigerated space for fruit from the Union.[15] The main South African exports to these markets were wool, maize, fruit, manganese and chrome ore.

Graph 1.3: Coal bunkered and exported from the principal South African ports, 1940-1945[16]

As the war progressed, Britain irregularly furnished the various exporting countries with a list of articles that should receive preference for export. This list included certain foodstuffs, metals, ores and textile raw materials. The only item exportable from South Africa at the time was wool. By March 1940, after some initial delays, a notable increase in British imports of wool from the Union was observed. Despite this increase, nearly 230,000 bales of wool destined for export to Europe remained stockpiled at various South African ports, primarily due to inadequate shipping. However, the shipment of manganese ore to the United States during this period posed no problem.[17] Although neutrality legislation precluded American vessels from entering areas proclaimed as war zones, South African waters at that stage were still not considered as such an area. The result was an increasing amount of American shipping diverted to the South African run. This diversion in shipping was organised principally through the South African Purchasing Commission in Washington, and through consultation with the American War Shipping Administration (WSA) and the British Merchant Shipping Mission in the USA.[18]

Fig 1.2: South African agricultural produce ready for export to the United Kingdom[19]

The South African Department of Railways and Harbours (SAR&H) operated a fleet of three ocean-going vessels. The SS Dahlia, SS Aloe and SS Erica operated in a triangular service between the Far East, Philippines, Borneo, Australia, Mauritius, Madagascar, Reunion, Beira and other coastal ports en route to Cape Town. This facilitation was, however, abandoned shortly after the outbreak of war as a result of the Axis and Allied naval operations in South African waters.

Several Vichy French merchant ships (henceforth merchants/merchantmen) became prizes of war during Operations Kedgeree and Bellringer – a joint action by the RN, South African Air Force and the Seaward Defence Force (SDF). These ships, together with other chartered and requisitioned vessels, including an oil-tanker, augmented the existing fleet to amount to no less than fifteen ships.[20] This fleet was employed on a variety of duties to circumvent the restriction that the wartime shipping burden placed on South Africa. These responsibilities included the transportation of UDF troops to the Middle East and the conveyance of petroleum products from the Middle East to the Union. The said vessels ensured that a large part of the Union’s urgent import requirements was carried in bulk and dispatched promptly. Included were supplies of grain, phosphates, railway sleepers and other timber, as well as more general cargo.

Following the Japanese conquests in the Far East, the Union had to search for new markets from which it could procure supplies of palm oil, rubber and oilseed, amongst others. South Africa was able to source these products from various countries in West Africa, who were able to meet the Union’s heavy demands for railway sleepers, timber, fish meal and coffee. In the course of 1942 a regular service was inaugurated by the SAR&H between the Union and a number of ports on the West African coast. Cargoes on the outward voyages consisted of South African exports, principally coal, cement, ore, manufactured goods and various foodstuffs. A lively business developed to the benefit of all the territories concerned.[21] Imports to South Africa, especially from the UK, proved unproblematic up until July 1941. Some importers complained about general delays, diversions and the nondelivery of imports, but these were inevitable consequences of the establishment of convoys coupled with mounting shipping losses in the North Atlantic. The available cargo space for imports was divided up between the urgent requirements of the South African war industries, basic civilian needs, and non-essential consumer goods. The South African ports also served the broader import and export requirements of Southern Africa for the duration of the war.[22] Throughout this period the UK shipped more commercial cargo to South Africa than any other country. Up until that time, however, the inhabitants of South Africa rarely felt the strain of war. This state of affairs was only possible as long as the allocation of adequate shipping space was not a significant determinant in the country’s import policy.[23]

Two leading causes lay the foundation for this state of affairs. First, until September 1941 the Union Government avoided introducing any strict controls over imports and exports, partly due to the unique internal political climate within South Africa.[24] Its reticence lay in stark contrast to the rest of the British Commonwealth. The Commonwealth abided by the controls instituted by the British Ministry of Economic Warfare early in the war to prevent any trading with the Axis powers. South Africa, however, required export permits from potential importers. The Department of Commerce and Industries introduced certificates of origin and interest in an attempt to effect a positive influence on the Union’s external trade. Importers were also required to apply for Essentiality Certificates. They could, in turn, provide the certificates to overseas suppliers for furnishing to their respective export control authorities. These measures were an official attempt by the Union Government to provide legitimate support for South African imports of scarce commodities and raw materials.[25]

.jpg)

Graph 1.4: South African wartime gold production, 1939-1944[26]

Second, the British export policy during the first two years of the war indirectly discouraged the South Africans from introducing any effective measures to control goods entering the country. The British export drive throughout this period attempted to secure enough foreign exchange to finance the war effort. This state of affairs had a profound impact on South Africa, none more so than after the introduction of the LendLease Act in March 1941. South Africa enjoyed a relatively privileged position in the Commonwealth due to its rich gold deposits and accompanying industries. The country therefore played a crucial role in the British export drive throughout this period. South Africa largely funded its war effort through its rich gold deposits, which secured a significant amount of foreign currency. This situation only changed once the Lend-Lease Act came into effect (see Graph 1.4).[27]

The introduction of the Lend-Lease Act held a number of misgivings for South Africa, none more so than forcing the Union to source her main imports of steel, nonferrous metals, machine tools, oil and motor vehicles from the USA. The Lend-Lease Administration also obligated the Union Government to provide firm evidence for the need of imports for the Union’s war effort.[28] This requirement coincided with an attempt by the American authorities to extend their export licensing. Lend-Lease material was either exempted or automatically licensed, as opposed to goods obtained from outside the parameters of Lend-Lease. Here, the requirement was for each country, including South Africa, to establish some form of import licensing to authenticate all orders placed in the USA by private traders.

South Africa established the Union Priority Board on 11 July 1941 to deal with all privately ordered goods from the USA which were subject to export licensing. On 10 September the Union Government instituted the Import and Export Control Board. The aim was to enforce a system of import control applicable to all non-sterling countries. The system of control was not comprehensive, yet it signalled the start of a radical change apropos import control. South Africa adopted a priority rating schedule to help facilitate imports from the USA. This structure eventually formed the foundation of a much stricter and more comprehensive system of import control from 1942 onwards.[29]

The UK’s export policy was influenced by the introduction of Lend-Lease, though it took some months for the British export drive to lose its momentum. A large number of British exporters were fearful of losing their business in South Africa to American exporters. They consequently clung to the South African market with much ardour.

The introduction of import licensing for goods purchased in the USA gave the South African importers ample warning of the prospect of future import restrictions. This led to hefty private orders of goods placed towards the end of 1941. Two concerns led to a dire state of affairs. They were the absence of import control over South African orders placed in the UK, and the fact that hardly any South African importers applied for Essentiality Certificates unless the goods ordered were subject to British export licensing. Thus neither the Department of Commerce and Industries nor the British Board of Trade (BOT), had any inkling as to what products were on order and what goods were bound for South Africa.[30]

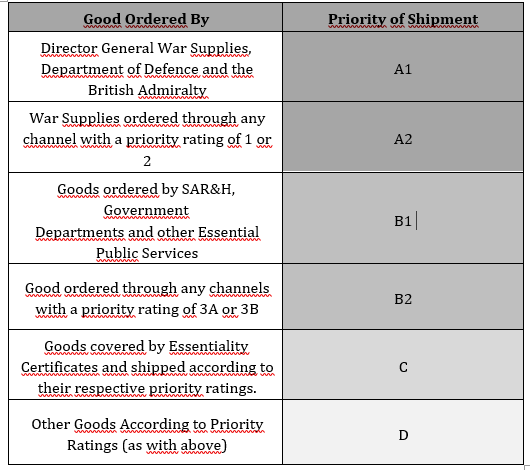

Fig 1.3: An Allied vessels taking on important local supplies, 1940s[31]

By the end of 1941, the global shipping crisis became a stark reality, adding an immense pressure to the Allied forces during the war. The most immediate causes of strain included the heavy demands for military needs in the Middle East; the American and Japanese entry into the war; the Japanese conquest of the Far East, and the mounting successes of the German submarines during the Battle of the Atlantic.[32] The British authorities had for some months, however, been aware of the changing military situation, and the impact that this would have on shipping requirements. The flow of imports to the Union during this period was nonetheless hardly interrupted. Both Union Government cargo and commercial goods were promptly shipped owing to the untiring efforts of the Stores and Shipping Branch located at South Africa House in London. Commercial imports duly amounted to between 40,000 and 50,000 tons per month in 1941.[33]

Be that as it may, the Union authorities were warned that such ample shipping provision was not possible in the future, as the UK faced increasing shipping shortages due to a large number of priority imports and essential war supplies destined for the Middle East. The outcome was an immediate reduction in the number of sailings to South Africa and the rest of the Commonwealth. Despite the warning passed by the MWT, none of the Commonwealth Governments fully grasped to what extent the shipping situation would deteriorate in 1942. The extension of the Allied war effort in that year created a heavy demand for shipping which far exceeded the available capacity of the Allies. The availability of shipping for imports became the main element influencing the South African economy and its accompanying war effort. Coupled with the question of port accessibility, was the lack of effective machinery for import control. The function of the machinery was to exclude non-essential goods from the everlengthening shipping queues. The MWT, however, doubted whether the South African authorities appreciated the seriousness of the situation facing the planning authorities in London. The Union government was thus increasingly urged to cooperate and match its imports to the greatly reduced shipping tonnage on hand.[34]

From the beginning of 1942, and well into 1943, the shortage of shipping to South Africa remained burdensome. As a result, economy in shipping became vital, especially in terms of eliminating unnecessary cargoes and making the most economical use of the available shipping. In an early attempt to gain a measure of control over the outstanding shipments to the Union, the establishment of the South African Advisory Shipping Committee was undertaken in April 1942. It was composed of representatives from the Shipping Section of South Africa House, the BOT, MWT, the London Chamber of Commerce, and various export groups and shipping lines.

The Advisory Shipping Committee’s arduous task was to sort essential orders from non-essential ones, as neither the BOT nor the Department of Commerce and Industries could provide any reliable data on outstanding cargo not yet shipped. Moreover, most of the orders from the UK were not covered by Essentiality Certificates and pre-dated the system of priority ratings. South African Importers were also often unaware that their orders were ready for shipment to South Africa. Similarly, British exporters with completed orders in their warehouses could not help in assessing the priorities of the goods for shipment.[35]

Fig 1.4: Key imports ready for delivery to Cape Town, 1940s[36]

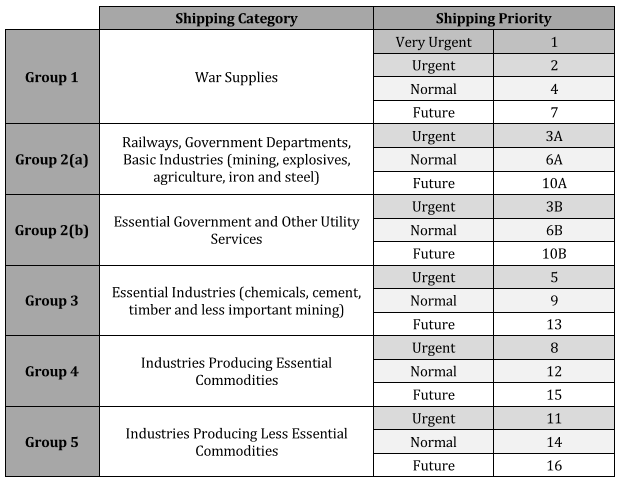

By May 1942 a central list of incomplete orders was drawn up through the assistance of the Chamber of Commerce in London, in an attempt to clear the substantial backlog of orders awaiting shipment to South Africa. This list was then matched with cables from South Africa requesting the shipment of selected goods. The cables enabled the MWT and BOT, in conjunction with South Africa House, the South African Trade Association and the South African Section of the London Chamber of Commerce, to draft a priority rating shipping schedule.[37]

The system of priority rating (see Table 1.1), along with Essentiality Certificates, formed the basis for the immediate control over the placement of shipping orders. It helped to determine which goods should be shipped, which goods should be shipped at a later date, and what cargo should not be shipped at all. At first, the priority rating schedule made allowance for ratings from 1 to 17, but the range was reduced to between 1 and 11 with the worsening of the supply position. No sooner than this had occurred, the BOT restricted future orders to South Africa to within the ratings 1 to 6.[38]

Table 1.1: Priority rating schedule for the shipment of cargoes to South Africa[39]

As an interim arrangement, the Union Government, provided a basis of division for the outstanding cargo. The cargo was to be apportioned into four main groups in order of importance to the South African war effort (see Table 1.2). This was, however, only a temporary solution to the overburdening South African shipping problem. Throughout the entire process, the South African authorities continually exacerbated the shipping problem by extending the system of priority rating. To their detriment, the authorities also issued Essentiality Certificates for goods not considered essential to the Union’s war effort. This action added to the accumulation of unshipped cargo, which by May 1942 amounted to at least 150,000 tons of cargo sitting aground in warehouses or at the docks in the UK. Orders held by exporters in various warehouses additionally amounted to 400,000 tons. To aggravate matters, the MWT could pledge a mere 5,000 to 6,000 tons of shipping per month on the South African run for the immediate future.[40]

Table 1.2 Interim four group division for outstanding cargoes for South Africa[41]

After the Union Government and the MWT reached an agreement, a license for export to South Africa became a prerequisite from the BOT. During the months of June and July 1942, the entire staff of South Africa House worked overtime in an attempt to assess shipping priorities. They also worked to issue Essentiality Certificates for shipments with a rating between 1 and 8 – contrary to the restrictions imposed by the BOT. After scrutinising the entire backlog of cargo, South Africa House issued nearly 23,000 Essentiality Certificates. It continued to issue Interim Certificates at a rate of 100 per day. With this formidable task accomplished, the function of the Advisory Shipping Committee was reduced to merely reviewing the broader issues surrounding the shipping situation and advising whether or not goods should be shipped. By August, all shipments with a priority rating above five were suspended, due to further wartime demands on available shipping. This increase in cooperation between South African and British authorities drew export cargoes from Britain to within manageable proportions. This collaboration, coupled with the opening of a Central Shipping Register in London for all cargoes destined for South Africa, allowed for the increasing matching of shipping with cargoes in the correct order of priority.145

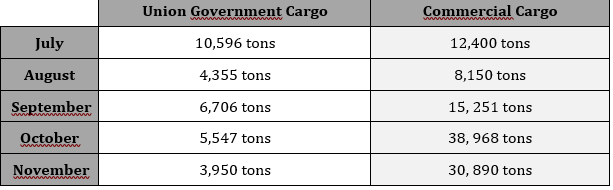

Despite these efforts, and the initial success of this scheme, the 5,000-6,000 tons of available shipping per month proved entirely insufficient in lifting the backlog of accumulated cargo. The Union Government estimated that it required at least 10,000 tons of shipping each month to merely lift the current cargo with a priority rating between 1 and 5. This ruled out the consideration of 60,000 tons of accumulated cargo with similar priority ratings. There was also a considerable tonnage of cargo rated 6 to 8 that awaited shipping. The MWT undertook to improve the situation during the remainder of 1942 after several presentations to the British Minister of War Transport, Frederick Leathers, the 1st Baron Leathers. An immediate result of this effort was the provision of additional shipping for the South African run between July and September (see Table 1.3). The likely target of 10,000 tons of shipping per month in both October and November was accordingly exceeded. By the end of 1942, the backlog of shipping with a high priority had decreased to a somewhat manageable 35,000 tons.[42]

Table 1.3: Ministry of War Transport shipments to South Africa, Jul-Nov 1942[43]

In January 1943, Lord Leathers made it clear that the substantial liftings accomplished towards the end of 1942 would be impossible to repeat. He warned that it would even prove difficult to maintain the minimum of 10,000 tons of commercial cargo per month. The MWT realised that it needed a comprehensive long-term shipping programme to address the Union’s import needs. Without such a programme, it was a challenge to plan and allocate equitable tonnage to South Africa. This was because the shipping situation was as yet unstable and liable to sudden fluctuations due to unforeseen crises.

In August 1942 the Combined Shipping Adjustment Board (CSAB) was created in Washington. The establishment of the CSAB helped to facilitate the process of combined planning of Allied shipping during the war. The MWT and the WSA became responsible for programming the shipping requirements of their respective areas of control.[44] Under this arrangement, South Africa were expected to provide the MWT with a detailed programme of its shipping requirements well in advance. These requirements were then assessed in combination with other claimants who were competing for the available, but limited, shipping space. The South African shipping programme thereupon received the required allocation of Allied shipping. Such detailed programmes of shipping allowed the CSAB to plan the global transportation of the maximum amount of goods in the minimum number of movements. It subsequently optimised return cargo opportunities and ensured the minimum wastage of shipping space.149 The result was a reduction of waste from production facilities, notably the manufacture of export goods which could not be shipped according to the system of priority ratings.

From August 1942 until January 1943 the MWT stressed the need for a forward programme to help plan for adequate shipping space. South Africa, like other countries, was slow to comply with the new requirements. The CSAB thus found it very difficult to plan to meet the Union’s required shipping needs, as well as the needs of Southern and Northern Rhodesia, East Africa, Madagascar and other African destinations, whose cargo passed through South African ports. This complacency naturally had a pernicious effect on the South African war economy.150

After the establishment of the CSAB, the responsibility for securing shipping from North American ports was shifted from the office of the South African Purchasing Commission in Washington to the Union High Commissioner’s Office in London. By the end of 1942, a serious shipping concern developed at North American ports that held grave consequences for the Union. Throughout the preceding year, the flow of cargo from North America to the Union was hampered by recurring crises, which threatened to disrupt both the South African private and armaments industries.

An American Economic Mission, headed by D.C. Sharpstone, visited South Africa in 1942 to evaluate first-hand the Union’s growing shipping requirements from the USA. This mission found that the Union’s war effort was largely dependent on raw materials and other crucial supplies shipped from North America. Upon its return to America, the Sharpstone Commission testified that the Union did indeed need a greater tonnage of shipping to maintain the function of its war economy. Sir Arthur Salter, head of the British Merchant Shipping Mission in Washington between 1941 and 1943, took up this grave matter with Lord Leathers so as to further press the Union’s urgent shipping needs upon both the British and American authorities. By the end of 1942, the MWT and the WSA agreed on a joint target of providing six merchants per month for carrying commercial and government cargo from North America to South Africa, the Rhodesias and East Africa. Through this course of action, the shipping situation somewhat improved, and the monthly expected tonnage of imports from North America averaged at 50,000 tons of cargo.[45]

for External Affairs, Cape Town, 27 Jan 1942. Also see Perry, ‘The Wartime Merchant Fleet and Postwar Shipping Requirements’, p. 527; M. Katz, ‘A Case Study in International Organisation’, pp. 4-6.

- DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 107, File War/C/131: Coordination of Allied War Effort – Control of Supply and Shipping. Telegram from High Commissioner, London, to Minister for External Affairs, Cape Town, 2 Mar 1942; Lewis, ‘The Inter-Relations of Shipping Freights’, pp. 58-59; Hancock and Gowing, British War Economy, pp. 412-417.

- DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. Clearing the Accumulation of Commercial Cargo, and the commencement of Combined Shipping Adjustment Board Procedure, Jun-Dec 1942. For more on the South African war economy, see Johnston-White, The British Commonwealth and Victory in the Second World War.

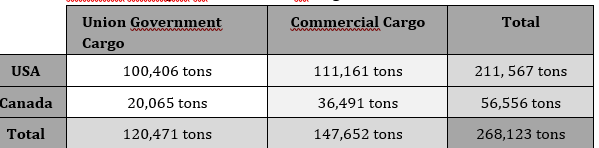

Summary of cargo awaiting shipment from North America to South Africa, Nov-Dec 1942[46]

In January 1943, there was nearly 270,000 tons of Union government and commercial cargo awaiting shipment from North America (see Table 1.4). Most of this consignment was needed by the Union armaments industries and for defence related matters. If shipping continued at the rate of 50,000 tons per month, it would take nearly six months to clear the accumulated cargo alone while making no allowances for new orders. The accumulation of steel at US ports destined for South Africa was also problematic. This was because the American authorities were adamant not to issue permits for new steel production for the Union because of a significant amount of unshipped steel at North American ports. The accumulated cargo also included smaller amounts of essential supplies. Included among the materials were industrial lubricants, sulphur and other chemicals for the munitions industry, ships stores for victualling convoys at Union ports, machine tools, timber, aircraft parts, textiles, agricultural machinery, paper and other necessities indispensable to the South African armaments industry and the civilian economy.[47] Despite various representations at a ministerial level to stress the seriousness of the shipping state of affairs, there was no reserve shipping pool on hand to alleviate the matter. South Africa also had to contend with the UK and the rest of the Commonwealth for the available shipping space.[48]Table 1.4:

South Africa met the shipping crisis head-on from January 1943. Henceforth the Inner Control Committee, of the Union Supply Coordinating Board, matched all import programmes to the Union. The Inner Control Committee decided between competing claims for shipping space to be allocated to the Department of Defence, the War Supplies Directorate, and urgent civilian needs. The system of priority ratings did, however, have one grave defect. Severe shortages were a constant threat since any order for a high priority commodity automatically took precedence over the shipment of goods of a lower priority. This occurred regardless of the date of the order, nor of its identified need.

To meet this established lack of balance, a ‘shipping term’, indicating the year and quarter for shipment (e.g. 3/44), was authorised on the Essentiality Certificates. The combination of the priority rating and the shipping term, which indicated the urgency of a shipment, provided the WSA and MWT with a ‘shipping indication’ of the order in which shipments should proceed. Goods of a high priority, would, if not shipped in the indicated quarter, be given a higher indicator in the following quarter.[49] The Inner Control Committee was able to satisfy some of the urgent needs arising from the shipping crises. This was done by issuing immediate over-riding priorities and providing the MWT and WSA with a schedule of the Union shipping requirements covering the period of January 1943 to June 1944.

South Africa’s shipping requirements from North America over this period were divided into three six-monthly periods, averaging 360,000 tons, 339,000 tons and 360,000 tons respectively. These figures were more than double the target allotted by the WSA and MWT and were entirely unrealistic.[50] Regrettably, the accumulation of unshipped cargo, especially steel, remained constant, so much so that the American War Production Board stopped the production of steel for South Africa until the level of unshipped steel had fallen below 25,000 tons.[51] Towards mid-1943 the shipping dilemma for South Africa became even more acute with the reopening of the Mediterranean to commercial traffic following the Allied successes in North Africa. The direct result was a drastic reduction in shipping around the Cape of Good Hope.158

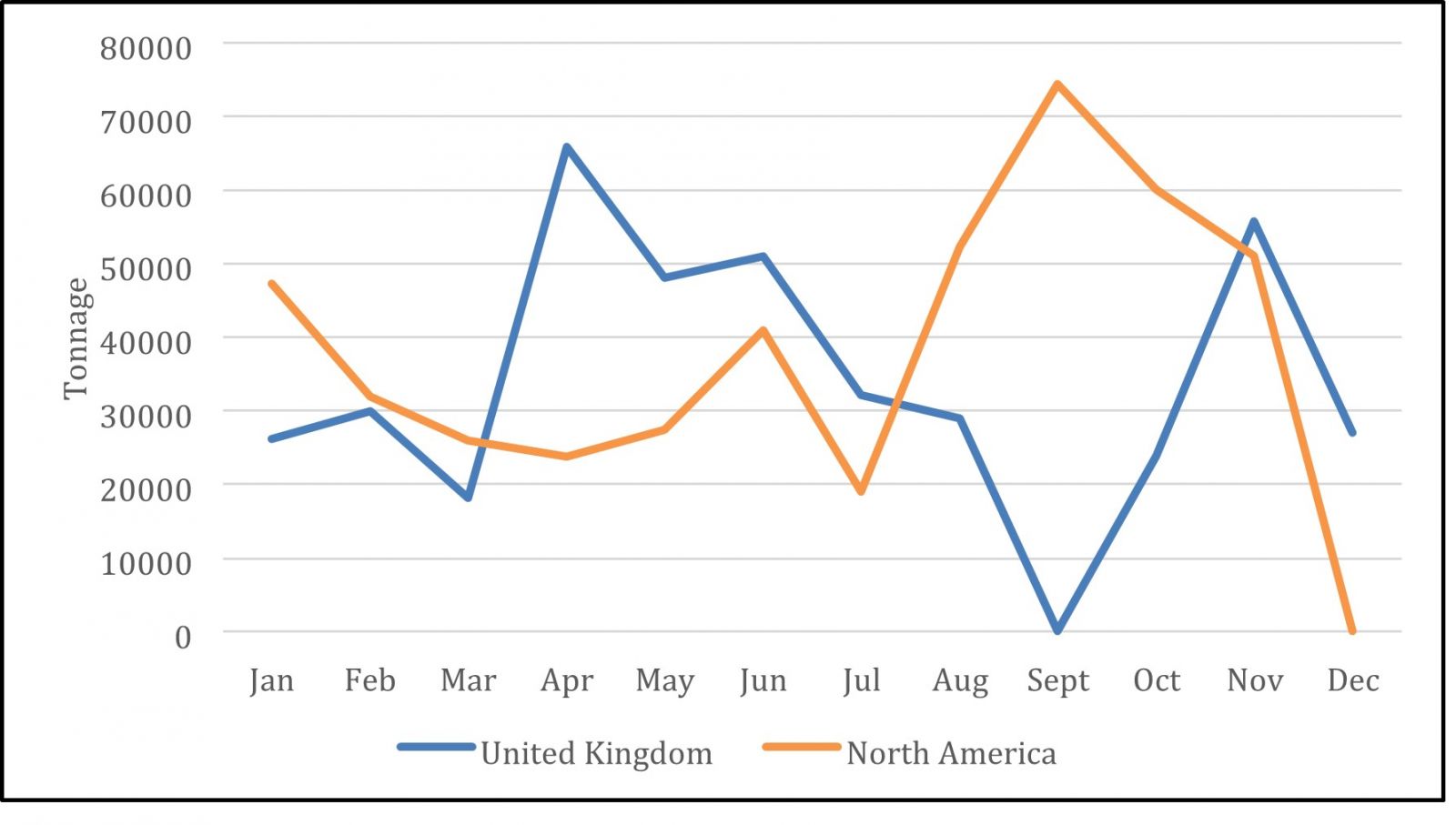

To meet the deteriorating shipping situation from North America, the MWT continuously tried to raise the shipping targets to South Africa. The British Merchant Shipping Mission also took up the matter with the WSA. Despite the general concern shown towards this affair, the new monthly target for shipping totalled only 45,000 tons – considerably less than the Union Government’s stated minimum requirement of 60,000 tons per month. By June of 1943, the MWT agreed to supply another ship for the North America/South Africa run for July and August. The provision would help ease the acute steel shortage in South Africa. This vessel shipped no less than 35,000 tons of steel, as well as an additional 6,000-7,000 tons of general cargo. By August, the shipping situation had improved despite the continuous accumulation of unshipped cargo at North American ports – then estimated at 224,000 tons, excluding steel. In September and October there was some respite, with eight additional ships dispatched from North America for the South Africa/Middle East coal service. The additional ships enabled the clearing of a substantial portion of the accumulated cargo. A gradual reduction in the Union’s shipping requirements from North America, coupled with the allocation of additional shipping space, thus greatly improved the shipping situation from North American ports by 1944 (see Graph 1.5).[52]

Graph 1.5: Comparative statement of shipping tonnage from the United Kingdom and North America to South Africa, Jan-Dec 1943[53]

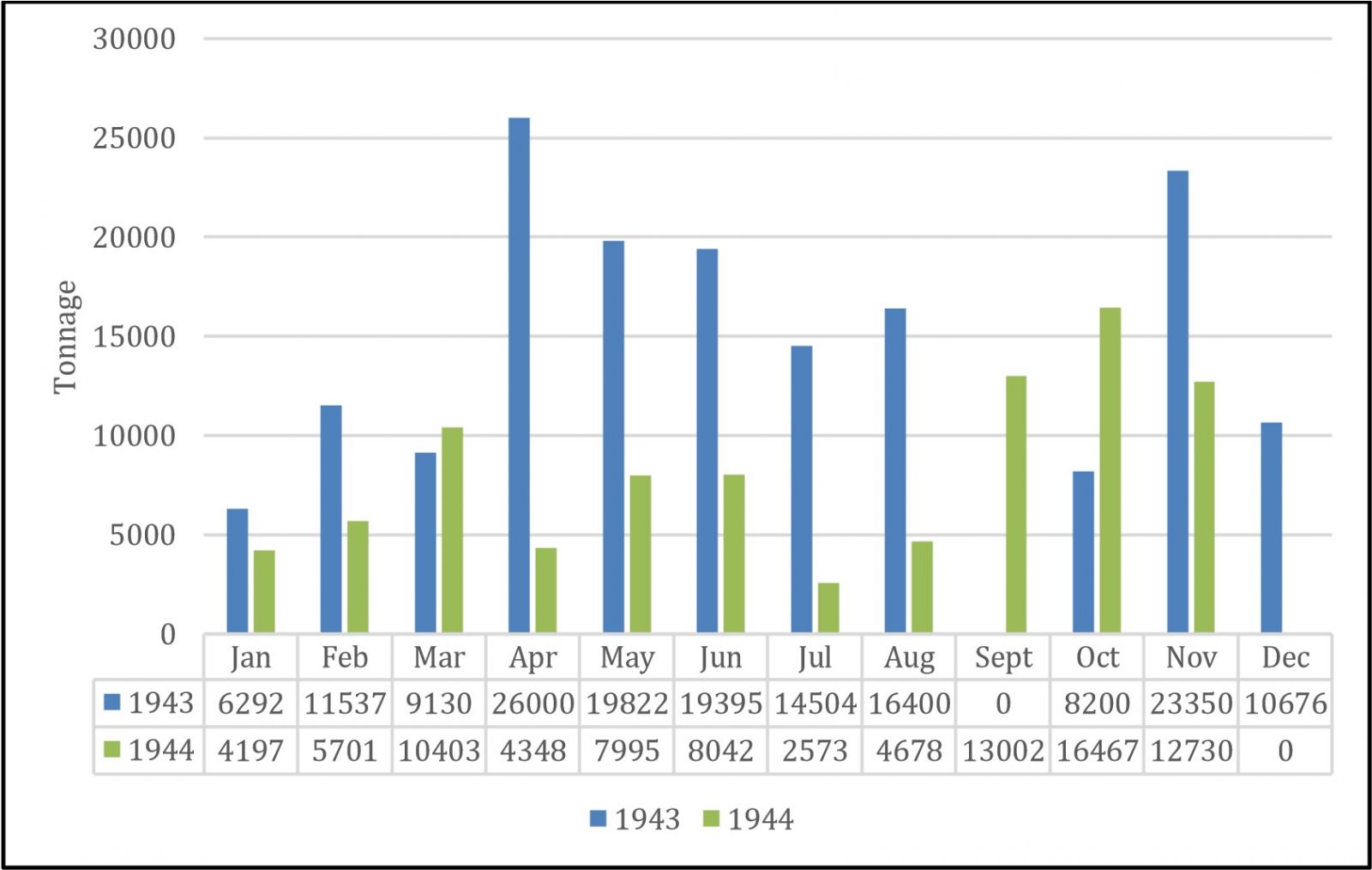

Even though South Africa’s shipping programmes from both the UK and North America proved satisfactory by mid-1944, shipments from the UK had improved somewhat earlier. In May 1943, there were only about 10,000 tons of accumulated cargo at British ports. As a result of improved priority ratings and larger shipments from Britain, there was a marked increase in the volume of non-essential goods that reached South African ports during the latter half of that year. In anticipation of further shipping improvements, the list of goods rated 1 to 5 was increased in February 1944 to include a host of non-essential goods. This period of ease in controls coincided with the build-up to the Allied invasion of France, and the concurrent Allied campaign in Italy. These incidents caused severe congestion at British ports. Between January and August 1944 the MWT was only able to reach the minimum target of 10,000 tons shipped to South Africa per month, and by June the accumulated cargo once more reached 30,000 tons. This was, notwithstanding, only a temporary shipping crisis, and by September the MWT resumed its regular shipping programme to South Africa (see Graph 1.6). Throughout the remainder of the war, and despite the ever-present stringency of the circumstances in which shipping found itself, no further crises impinged on the South African shipping programme.[54]

Graph 1.6: Shipments of commercial cargo from the United Kingdom to South Africa, 1943-1944[55]

The Union of South Africa emerged from the war without having faced a severe breakdown of its war economy, and without severe civilian austerity. This was a remarkable feat considering the earlier unreliable import controls and the lack of strategic foresight regarding planning of shipping freight. Had the Union Government previously adopted self-imposed restrictions of consumption at an earlier stage, it might have alleviated the shipping troubles it faced at the beginning of 1942. South Africa could do nothing to improve the position of shipping by itself, except to cooperate fully with the Anglo-American shipping authorities throughout. The fact remains that the combined policies of the Union Government, the MWT, WSA, and even the CSAB, were unable to alter the global shipping situation throughout the war.

Several geographic, economic and military variables imposed a number of limitations on the planners who aimed to meet the shipping predicament head-on. Some of these factors favoured South Africa from a shipping perspective. Others had such effects that troubles with shipping were merely perpetuated. South Africa’s saving grace was its geographic location astride the strategic shipping route to and from the Middle East, which meant that there was always plenty of shipping passing through South African waters. Had the Mediterranean remained open to shipping throughout the war, the Union would have fared much worse from a shipping point of view. Despite this geographic advantage, the Union was unable to produce significant export surpluses which formed a vital part of the British and American import programmes. This shortcoming naturally increased the difficulty of providing a higher regular tonnage of shipping for the Union. Without return cargoes, the loss to the UK import programme in particular, would have crippled the Allied war effort.

[1] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. Introduction and Background to the Shipping Crisis of 1942/1943.

[2] Slader, The Fourth Service: Merchantmen at War 1939-45, pp. 13-17. Also see Roskill, A Merchant Fleet in War 1939-1945; Smith, Conflict over Convoys: Anglo-American Logistics Diplomacy in the Second World War.

[3] Union Office of Census and Statistics, Official Yearbook of the Union of South Africa, No. 23, Chapter XXIV, pp. 14-21. Also see for instance Gardner, Decoding History: The Battle of the Atlantic and Ultra.

[4] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. Introduction and Background to the Shipping Crisis of 1942/1943.

[5] For a more in depth discussion of the Battle of the Atlantic see Gardner, Decoding History: The Battle of the Atlantic and Ultra; Lautenschlager, ‘The Submarine in Naval Warfare, 1901-2001’, pp. 94-140; Cousineau, Ruthless War, 2007.

[6] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 73, File: Year Book, Section XI. Shipping.

[7] North-West University (NWU), Records, Archives and Museum Division (RAM Div) (Potchefstroom), Ossewabrandwag Archive (OB Archive), A.F. Schulz Versameling. Nazisme in Andalusia Interneringskamp, 9 Okt 1940 – 22 Nov 1944. For more on this, see Moore, ‘Unwanted Guests in Troubled Times’, pp. 63-90; Malherbe, Never a Dull Moment, p. 215.

[8] Martin and Orpen, South Africa at War, p. 325; Clarence-Smith, ‘Africa’s “Battle for Rubber” in the Second World War’, p. 168. Also see Feinstein, An Economic History of South Africa.

[9] Leighton and Coakley, Global Logistics and Strategy, 1940-1943, p. 47; Stewart, The First Victory, pp. 48-52; Katz, Sidi Rezegh and Tobruk, pp. 6-8, 25. The latest South African work to appear on the campaign in North Africa is Katz, South Africans versus Rommel.

[10] South African National Museum of Military History, Masondo Reference Library. SA Navy Photo

Collection, S.A. 459.

[11] Murray and Millett, A War to be Won, pp. 92-98, 110-120, 169-181; Hammond, ‘British Policy on Total Maritime Warfare’, pp. 789-790. Also see Ball, The Bitter Sea: The Struggle for Mastery in the Mediterranean, 1935-1949.

[12] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. Introduction and Background to the Shipping Crisis of 1942/1943.

[13] Union Office of Census and Statistics, Official Yearbook of the Union of South Africa, No. 23, Chapter XXIV, pp. 26-28.

[14] The Eastern Group Supply Council was a wartime body established in 1940 with the sole intention of coordinating the build-up of war materiel in the British colonies and dominions east of the Suez Canal. Their ultimate aim was to reduce the amount of supplies shipped from the United Kingdom.

[15] Albertyn, Upsetting the Applecart, p. 11. DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. Introduction and Background to the Shipping Crisis of 1942/1943; Lewis, ‘The Inter-Relations of Shipping Freights’, pp. 58-59.

[16] Union Office of Census and Statistics, Official Yearbook of the Union of South Africa, No. 23, Chapter XII, p. 16.

[17] Brown, ‘African Labor in the Making of World War II’, pp. 64-65; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 73, File: Year Book, Section XI; Shipping; Postan, British War Production, p. 157.

[18] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 12, File: SA War Economy 1939-1945. Procurement of Supplies – SA Purchasing Organisation in USA; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 35, File PO/29. South African Purchasing Commission Inception and Organisation, 1940-1947.

[19] South African National Museum of Military History, Masondo Reference Library. SA Navy Photo Collection, S.A. 1703.

[20] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 47-54; Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 89-95.

[21] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 24, File: SA Railways and Harbours Departmental Civil War History Vol VIII. Ports & Shipping.

[22] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 73, File: Year Book, Section XI; Shipping. See for instance, Dumett, ‘Africa's Strategic Minerals During the Second World War’, pp. 381-408; Tembo, ‘Rubber Production in Northern Rhodesia’, pp. 223-255.

[23] Henshaw, ‘Britain, South Africa and the Sterling Area’, pp. 208-209.

[24] For more on this unique political situation see Marx, Oxwagon Sentinel.

[25] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. Introduction and Background to the Shipping Crisis of 1942/1943; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 111, File: Import Control. Certificates of Essentiality.

[26] Union Office of Census and Statistics, Official Yearbook of the Union of South Africa, No. 23, Chapter XXII, p. 27.

[27] Martin, ‘The Making of an Industrial South Africa’, p. 84; Henshaw, ‘Britain, South Africa and the Sterling Area’, p. 208; Dumett, ‘Africa's Strategic Minerals During the Second World War’, pp. 383-384; Van der Waag, A Military History of Modern South Africa, p. 191.

[28] Byfield, ‘Producing for the War’, pp. 27-28.

[29] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 73, File: Year Book, Section XI; Shipping; Albertyn, Upsetting the Applecart, p. 13.

[30] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. Introduction and Background to the Shipping Crisis of 1942/1943.

[31] South African National Museum of Military History, Masondo Reference Library. SA Navy Photo Collection, S.A. 1227.

[32] This viewpoint is furthered by Boyd, The Royal Navy in Eastern Waters: Linchpin of Victory 19351942 as well as Neidpath, The Singapore Naval Base and the Defence of Britain's Eastern Empire, 1919-1941.

[33] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. Shipment of Union Government Cargo from the United Kingdom.

[34] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. Introduction and Background to the Shipping Crisis of 1942/1943; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. The Beginning of Shipping Control over Commercial Cargo.

[35] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 73, File: Year Book, Section XI; Shipping; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 114, File: Priority Rating. Backlog of Cargo from UK.

[36] South African National Museum of Military History, Masondo Reference Library. SA Navy Photo Collection, S.A. 1201.

[37] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. The Beginning of Shipping Control over Commercial Cargo; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 107, File War/C/131: Coordination of Allied War Effort – Control of Supply and Shipping. Telegram from the Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs, London, to the Minister of External Affairs, Cape Town, 28 Jan 1942.

[38] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 108, File: Import Control. Priority Rating; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 111, File: Import Control. Priority Rating Shipping.

[39] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. Appendix I.

[40] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. The Beginning of Shipping Control over Commercial Cargo.

[41] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. Appendix II. 145 DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 73, File: Year Book, Section XI; Shipping.

[42] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. Clearing the Accumulation of Commercial Cargo, and the commencement of Combined Shipping Adjustment Board Procedure, Jun-Dec 1942; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 113, File: Shipping – Shipping for July and August 1942. Telegrams from South African Litigation, Washington to PrimeSec Pretoria, 22 Jul 1942; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 113, File: Shipping – Position in June 1942. Telegram from Oppositely, London, to South African Litigation, Washington 17 Jun 1942.

[43] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. Clearing the Accumulation of Commercial Cargo, and the commencement of Combined Shipping Adjustment Board Procedure, Jun-Dec 1942.

[44] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 107, File War/C/131: Coordination of Allied War Effort – Control of Supply and Shipping. Telegram from Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs, London, to Minister

[45] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. The Effect of Combined Shipping Procedure upon the Responsibilities of the Union High Commissioner’s Office 1942-1944.

[46] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. The Effect of Combined Shipping Procedure upon the Responsibilities of the Union High Commissioner’s Office 1942-1944.

[47] Close, ‘South Africa's Part in the War’, p. 187; Dumett, ‘Africa's Strategic Minerals During the Second World War’, pp. 386-387.

[48] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 73, File: Year Book, Section XI; Shipping; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. The Effect of Combined Shipping Procedure upon the Responsibilities of the Union High Commissioner’s Office 1942-1944.

[49] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 108, File: Import Control. Shipping Term Allocation; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 110, File: Import Control. Shipping Term System.

[50] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. The Effect of Combined Shipping Procedure upon the Responsibilities of the Union High Commissioner’s Office 1942-1944.

[51] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 110, File: Procurement. Steel Shipment and Orders at Hand; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 110, File: Shipping. Shipment of Steel Supplies. 158 Van der Waag, A Military History of Modern South Africa, pp. 200-203.

[52] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 73, File: Year Book, Section XI; Shipping; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 60, File: C 38. Wartime Shipping Problem.

[53] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 36. File: Shipping. Statement of Shipments from the United Kingdom during the Period Jan to Dec 1943; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 36. File: Shipping. Statement of Shipments from North America during the Period January to December 1943.

[54] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 112, File: Import Control. Priority Rating in Relaxation to Shipping; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 111, File: Shipping. Position in 1945; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. The Effect of Combined Shipping Procedure upon the Responsibilities of the Union High Commissioner’s Office 1942-1944.

[55] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 16, File: The War Time Shipping Problem. The Effect of Combined Shipping Procedure upon the Responsibilities of the Union High Commissioner’s Office 1942-1944.