THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

14)RIVAL MARITIMES STRATEGIES

1.2 Rival maritime strategies off the South African coast – a question of shipping?

On 6 September 1939, the Union of South Africa became an active participant in the Second World War when it joined the Allied cause and declared war on Germany. South Africa’s strategic position regarding geographical location would be a key determinant of both the Axis and Allied maritime strategies throughout the war.

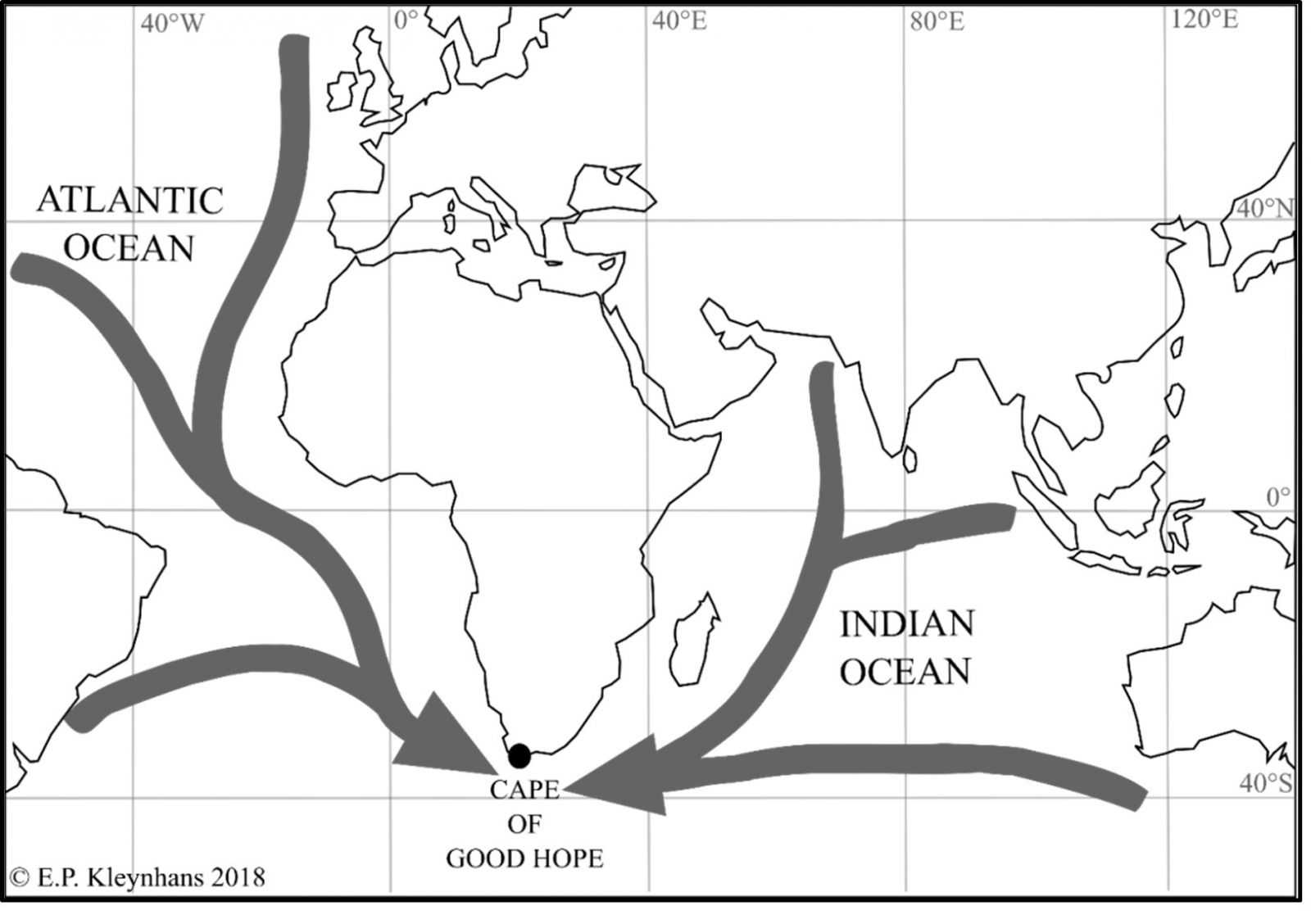

The waters off the Cape of Good Hope, which formed a critical maritime nodal point, became a vital link in the main Allied supply routes to and from the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent and the Far East.[1] Although geographically removed from the main area of naval operations in the North Atlantic, South Africa had to contend with a great increase to the usual sea traffic that flowed through its ports. South Africa also had to ensure the safe passage of all friendly shipping travelling along its coastline, and safeguard shipping that visited its ports. At that point in time, the South African coastline stretched from the mouth of the Kunene River on the Atlantic Ocean to Kosi Bay on the Indian Ocean. Thean Potgieter, a South African naval historian, came to the conclusion that the Cape of Good Hope was the real centre of the British Empire until perhaps the 1870s (see Map 1.1). This is because it was equidistant from Australia, China, India, Gibraltar, the West Indies and the Falkland Islands.[2] The British historian Paul Kennedy supports this view. He maintains that Cape Town was perhaps “the most important strategic position in the world in the age of sea power.”[3]

Jamie Neidpath, however, states that the Cape of Good Hope was only one of the five keys which locked up the British Empire, along with Singapore, Alexandria, Gibraltar and Dover. Neidpath, in contrast to Kennedy, suggests that the true centre of the British Empire was east of the Suez Canal in the Indian Ocean. He maintains that the three keys for continued control over the Indian Ocean was British possession of the Cape of Good Hope, Aden and Singapore. British control over Egypt and the Middle East remained crucial too, as such control guarded access to one of the principal maritime trade routes passing through the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean. Neidpath finally argues that a strong British naval presence in Singapore was essential to keep Australia and New Zealand within the imperial orbit, while it also acted as a gateway to the Pacific during the war.[4] If the British, however, lost control over one of the three keys to the Indian Ocean – as it did after the fall of Singapore in February 1942 – there would be a series of drastic military, economic and logistical consequences to the overall Allied war effort. Moreover, control over the remaining two keys to the Indian Ocean would then became extremely important, in large degree due to the observed interconnectivity of the Allied war effort.

Map 1.1: Strategic location of the maritime nodal point of the Cape of Good Hope

On 30 January 1939 the Admiralty approved the RN’s war plans for the imminent global conflict. These plans primarily dealt with the waging of concurrent naval wars against Germany and Italy, as British defence planners did not expect Japan to initially side with the Axis Powers during the opening stages of the war. Nonetheless, the naval war plans stated, as a secondary consideration, that the RN should anticipate Japanese naval hostility aimed at both Britain and France. The British expected Germany in particular to dispute its maritime control in two distinct ways: through its available surface warships and disguised merchant raiders; and through a sustained submarine offensive aimed at destroying British and Allied seaborne commerce. The basis of the British maritime strategy during the war was thus to maintain command at sea and establish zones of maritime control at key locations across the globe.[5]

The Admiralty considered the continued operation of key ocean trade routes as imperative to its naval strategy. The ocean passages passing through the Mediterranean from the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent and the Far East were markedly crucial. The loss of these trade routes due to Axis naval operations would force the Admiralty to divert Allied merchant traffic along the longer but potentially safer sea route around the Cape of Good Hope.[6] The RN thus deployed a number of anti-submarine (A/S) hunting units at strategic locations across the globe to help protect critical maritime trade routes. The protection of these maritime trade routes became the responsibility of the RN’s foreign naval commands. These commands were comprised of the North Atlantic Station (Gibraltar), South Atlantic Station (Freetown), the America and West Indies Station (Bermuda), the East Indies Station (Ceylon) and the China Station (Singapore and Hong Kong). The Dominion Navies also each accepted a measure of responsibility for control of the waters adjacent to their territories. Such acceptance of responsibilities was, however, dependent on their individual strengths and capacity. The British maritime strategy also called for the total economic blockade of Germany from the outset of war.[7]

The key to the Allied naval strategy in South African waters was the establishment of a definite maritime zone of control in order to ensure the continued safe passage of merchant shipping around the Cape of Good Hope. The defence and sustained operation of this key shipping route was thus not only a South African problem. Because of its vital importance to the war effort, it was also a combined Allied dilemma. British and South African defence planners estimated that the main aim of the Axis naval operations in South African waters would be to sever the Allied maritime trade routes to and from the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent and the Far East. The majority of maritime attacks were thus expected in the areas where the sea traffic would be most concentrated and congested – the ports of Durban, Port Elizabeth and Cape Town (see Map 1.2).[8]

Map 1.2: Principal southern African harbours

The defence of South Africa’s maritime trade routes throughout the war fell into two broad categories. In order to ensure the maintenance of sea communications around the South African coast, the Union’s threat perception and counter-measures had to take into consideration the differing maritime perils prevalent in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The maritime menace off South Africa’s Atlantic coast was initially confined to German submarines and surface raiders operational in the South Atlantic. British Naval Intelligence estimated that German naval activity off the South African coast would be limited, especially owing to the vast operational distances involved. The combined threat was exacerbated by the fact that both U-boats and surface raiders were known to have the ability to mine vital coastal junctures along the South African coastline.[9]

The maritime threat along South Africa’s Indian Ocean coast was confined to that of Japanese and Italian naval forces operational in the area. Despite its nearest base being 5 000 miles away, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) posed a direct menace to the merchant traffic off the entire South African eastern seaboard. This was especially the case when the IJN was provisioned from the Vichy French in Madagascar and possible subversive elements in Portuguese East Africa. The closest maritime danger to South Africa in 1940 came from the Italian submarines known to be based in the Red Sea port of Massawa, a mere 3 800 miles from the strategic port of Durban. The presence of Japanese and German warships in the Southern Atlantic and Indian Oceans was deemed a possibility, but thought of as unlikely.89 The Chief of the General Staff of the Union Defence Force (UDF), Lt Gen (Sir) Pierre van Ryneveld, anticipated that the primary naval risk to South Africa was posed by the Japanese and Italian submarines active in the Indian Ocean. The German threat was considered, but discarded due to the vast operational distances involved in deployments to the Indian Ocean.90 These threat perceptions prevailed well into 1944, and even extended into 1945.

In May 1939 the Kriegsmarine, the German Navy, received its battle instructions for the impending conflict. In the event of war, the German Navy would be tasked with protecting the German coastline and its seaborne communications, attacking the shipping of its adversaries, and supporting land and air operations along the German coastline. Most importantly, it would act as a strategic-political instrument of war. Owing to the negligible strength of the Kriegsmarine, however, Germany had no specific maritime strategy to follow on the eve of the Second World War.91 The Oberkommando der Marine92 (OKM) accepted the naval inferiority of the Kriegsmarine from the outset. Along with the Seekriegsleitung93 (SKL), the OKM advocated the aggressive deployment of its available naval forces in operations against British and Allied seaborne trade in the North Atlantic.94

of the General Staff (CGS) War, Box 122, File: Raiders. Secret report on possible operation of Italian submarines in the Indian Ocean, 3 July 1940.

- DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 126, File: Coastal appreciations general. A Japanese attack on South Africa: An appreciation from the enemy point of view, 29 Sept 1942; DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 126 File: Coastal appreciations general. Most secret communication between DECHIEF and OPPOSITELY regarding the scales of attack by sea and air in South African waters, 8 April 1943; DOD Archives, CGS War, Box 122, File: Raiders. Secret report on possible operation of Italian submarines in the Indian Ocean, 3 Jul 1940.

- DOD Archives, CGS War, Box 122, File: Raiders. Secret report on possible operation of Italian submarines in the Indian Ocean, 3 Jul 1940.

- Raeder, Grand Admiral, pp. 279-281.

- The Oberkommando der Marine was the High Command of the German Navy. As such it was the highest administrative and command authority of the Kriegsmarine.

-

The Seekriegsleitung was the Maritime Warfare Command of the Germany Navy. 94 Raeder, Grand Admiral, pp. 282-286.

The German naval war plans explicitly focused on trade warfare on the open oceans. The aim was firstly a concentrated confrontation with British and Allied merchant shipping through surprise attacks by disguised merchant raiders. The war plans further called for the laying of a series of minefields at critical coastal junctures across the globe. Lastly, the naval war plans focussed on the use of the U-boats in operations aimed at disrupting and destroying British seaborne trade. The OKM intended to use its submarines to work against British and Allied shipping in the areas where its surface raiders were not operational, and where the sinking potential was significant.[10][11] U-boat operations were hence earmarked for the North and Central Atlantic, the West Indies, the waters off the Cape Verde Islands, Freetown in Sierra Leone and the Bay of Biscay. As an additional measure, the German naval war plans called for surface raiders and submarines, along with a few capital ships, to deploy to their respective operational areas before the declaration of war, and to strike an immediate and decisive blow to British and Allied shipping.[12]

During the first two years of the war, the German maritime strategy was solely focussed on continuing its successes in the Battle of the Atlantic, where it managed to reduce British imports from 55 million tons in 1939 to a mere 35 million tons in 1941. By operating as far afield as the Mediterranean, Brazil and West Africa, the U-boats were on the brink of sinking Allied merchant shipping faster than it could be replaced. By 1942 the Battle of the Atlantic reached its pinnacle when the U-boat successes in the North Atlantic started to dwindle. These decreasing losses were the result of the increasing skill of Allied convoy and escort commanders; reliable submarine detection equipment and significant improvements in A/S weapons. Furthermore, the Allied ability to read German naval ciphers by mid-1941; a higher numbers of escorts, and the diminished ‘air gap’ in the North Atlantic contributed to the dwindling of U-boat successes. Along with these, the heavy loss of skilled personnel in the German Navy directly led to a decline of moral and combat effectiveness.[13]

In 1941, a Befehlshaber der U-Boote (BdU)[14] appreciation highlighted the fact that the Cape Town–Freetown convoy route would make an excellent target for a concentrated U-boat offensive. This possibility was highly conceivable especially as the closure of the Suez Canal would lead to the redirection of all seaborne trade around the Cape of Good Hope. The Cape Town–Freetown convoy route passed along the strategic maritime nodal point of the Cape of Good Hope, with a great number of ships passing through South African ports. By the end of October, the BdU had temporarily withdrawn all U-boats from the West Coast of Africa. The disengagement was due to a considerable reduction in British shipping along this trade route, which effectively denied the area of the sinking potential required to sustain a U-boat offensive.[15] By February 1942 the operational situation once more changed, especially after the B-Dienst[16] reported that there was a definite increase in British transatlantic shipping along the Cape Town Freetown route.[17]

By the latter half of 1942, the BdU concluded that the sinking results in the North Atlantic had decreased to such an extent that a U-boat operation off the southern African coast proved viable. Such an endeavour would also cause a diversionary effect, forcing the Allies to split their naval forces between protecting the North Atlantic, the American Eastern seaboard and the Atlantic coast of Africa.[18] Moreover, South African waters were still considered ‘virgin’ waters by the BdU. Despite some previous forays, the BdU did not favour sending single U-boats to operate off the southern African coast. Their independent actions would alert the Allies and force the adoption of stringent A/S measures. A single submarine operating off the South African coast would furthermore not reach the satisfactory sinking results needed to justify its deployment. The BdU realised that any operation in South African waters could only materialise once adequate numbers of U-boats were accessible to launch a concentrated attack, and sustain it for an indefinite period to allow for sufficient sinking results. The primary focus throughout the naval conflict was the waging of a war of tonnage through the sinking of Allied merchant shipping, and not merely the tying down of enemy naval forces through diversionary attacks.[19]

[1] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 1; Meyer, ‘From Spices to Oil’, pp. 1-10. See also Malyon, ‘South African Shipping’, pp. 438-446; Neidpath, The Singapore Naval Base and the Defence of Britain's Eastern Empire, 1919-1941, pp. 2, 6, 9, 13, 38.

[2] Potgieter, ‘Maritime Defence and the South African Navy’, p. 164; This view is further reinforced by Dörning, ‘The West and the Cape Sea Route’, pp. 46-47; Close, ‘South Africa's Part in the War’, p. 185.

[3] Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery, pp. 129-131.

[4] Neidpath, The Singapore Naval Base and the Defence of Britain's Eastern Empire, 1919-1941, pp. 2, 6, 9, 13, 38.

[5] Roskill, The War at Sea: Volume I – The Defensive, pp. 41-45; Carroll, ‘The First Shot was the Last Straw’, p. 407.

[6] Roucek, ‘The Geopolitics of the Mediterranean, I’, pp. 349-354; Roucek, ‘The Geopolitics of the Mediterranean, II’, pp. 71-80; Martin and Orpen, South Africa at War, p. 7; Roskill, The War at Sea: Volume I – The Defensive, p. 42.

[7] Roskill, The War at Sea: Volume I – The Defensive, pp. 42-43; Jackson, ‘The Empire/Commonwealth and the Second World War’, pp. 67-70.

[8] Department of Defence Documentation Centre (DOD Archives), Diverse, Group 1, Box 126, File: Coastal appreciations general. A Japanese attack on South Africa: An appreciation from the enemy point of view, 29 Sept 1942; DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 126, File: Coastal appreciations general. Most secret communication between DECHIEF and OPPOSITELY regarding the scales of attack by sea and air in South African waters, 8 Apr 1943.

[9] DOD Archives, Diverse, Group 1, Box 126, File: Coastal appreciations general. A Japanese attack on South Africa: An appreciation from the enemy point of view, 29 Sept 1942; DOD Archives, Chief

[10] Cousineau, Ruthless War, pp. 100, 182-183; Roskill, The War at Sea: Volume I – The Defensive, p.

[11] .

[12] Raeder, Grand Admiral, pp. 283, 287-288.

[13] Tarrant, The U-boat Offensive 1914–1945, pp. 100–101. For a more in depth discussion see for instance Rossler, The U-boat: The Evolution and Technical History of German Submarines and Howarth and Law (eds.), The Battle of the Atlantic 1939-1945; Milner, ‘The battle of the Atlantic’, pp. 45-66.

[14] It was the title of the supreme commander of the Kriegsmarine’s U-boat Arm during the war, but also referred to the Command HQ of the U-boat arm itself.

[15] Doenitz, Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days, p. 176.

[16] The B-Dienst was the cryptographic section of the Naval High Command, which helped to monitor Allied radio traffic and hence tried to decipher these messages. See Doenitz, Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days, p. 242.

[17] Doenitz, Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days, pp. 213–214.

[18] Busch, U-Boats at War, pp. 146-147; Doenitz, Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days, p. 238.

[19] DOD Archives, Union War Histories (UWH) Civil, Box 341, File: U-Boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters. Hessler incidentally also wrote the British confidential account of the U-boat war, which was published in 1989 as The U-Boat War in the Atlantic 1939-1945.