- PRECIOUS CARGO LOST

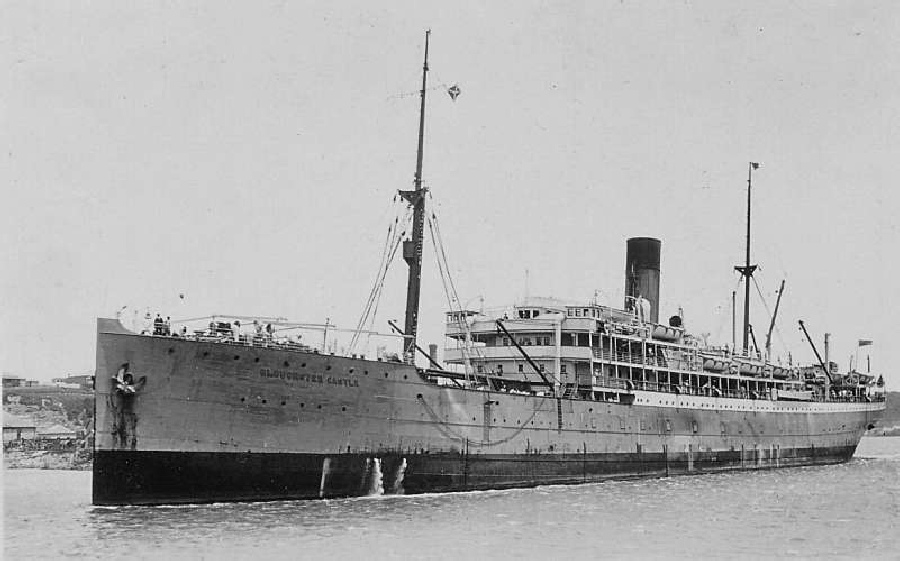

13)GLOUCESTER CASTLE (RAIDER MICHEL)

Photo. http://www.bandcstaffregister.com/page41.html

Built: 1911

Tonnage: 8,003 / 9,235 tons

Cargo: Aircraft, military equipment, machinery and gasoline 5,000 tons (est)

Route: Birkenhead UK – Table Bay

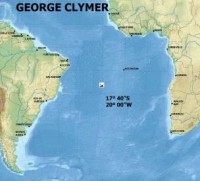

Sunk by Michel 15/07/42 on pos. 08º 00’S 01º 00’E

124 Dead

41 Survivors

On June 20th 1942 the 8,000 ton ‘Gloucester Castle’ commanded by Captain Rose left Liverpool bound for Cape Town with 165 people aboard, including 12 women and 4 children as passengers.

I was making my second voyage in the ship as a quartermaster, and at the time was congratulating myself on my good luck for she was the sixth ship I had served in since the beginning of the war without once being sunk by enemy action.

After safely passing through the Atlantic haunts of enemy submarines we left our convoy south of Freetown, Sierra Leone and stood well out into the Atlantic. We never reached our destination for the Gloucester Castle was one of those ships, which disappeared without trace in the South Atlantic at that time.

The evening of 15th July saw her a darkened ship under a clear starry sky standing steadily on her course and lifting gently to the slight swell, when, a few minutes before 7 o’clock without warning she shuddered under the impact of a salvo of bursting shells. Off watch and below decks, I was suddenly startled by a series of ear splitting explosions as the shells crashed into the ship. For the next eight minutes, until she broke up and plunged to the bottom, all hell seemed to be let loose. In a matter of seconds the ship was afire from stem to stern.

As the shells crashed unceasingly into her she leapt like a living thing out of the water as a torpedo struck her amidships with a terrific explosion. Trapped below by the fire, which swept the ship, my shipmate and I lost valuable seconds in gaining the deck and our action stations. With our only exit to the open deck blocked by solid sheets of flame and the suffocating smoke fast choking us, it seemed certain that we would be burnt to death. But by charging through the flames in desperation some of us did manage to reach the deck. Several of our shipmates failed in that mad dash or hesitated too long and perished in the inferno.

It was evident that the ship was doomed and could not last long. The bridge and most of the boats had been shot away and she was settling fast by the stern. As I ran along the shell swept boat-deck, the second and third radio operators passed me on their way to assist their senior on watch in the wireless room. Even as they entered the cabin a vivid flash of red flames momentarily blinded me as the whole structure burst asunder under a direct hit.

Many people were jumping into the sea to escape the bursting shells and raging fire. Alone as we were in the middle of the ocean with no hope of immediate assistance our only chance was to get away in what boats were left. Already one boat with women and children in it was clear of the ship, thanks to the coolness and devotion to duty of the boatswain who refused to leave in the boat himself and so forfeited his life. In a desperate fight against time we fought to clear away the damaged boats, and succeeded in dropping one in the water before the boat deck on which we stood became awash. Then with a sickening roll and shudder the ship broke up and sank, taking down with her all of us who were still aboard.

In spite of my desperate struggles to regain the surface the pressure on my head and in my ears increased as the suction drew me ever deeper and my lungs threatened to burst.

If this was the pleasant death of drowning I had heard about I prayed for the end of it, but the time seemed interminable. With my weakening struggles came the blissful oblivion until consciousness returned and I found myself yet again on the surface.

Blacker than the night itself was a thick black smoke pall left behind by the ship, and all around me was a sea covered with wreckage. With what little strength I had I struck out for a spar to which I thankfully clung having lost my life belt in the downward plunge. As I hung on to my support inhaling great gulps of air, giving release to my tortured lungs, slowly my strength returned and I was able to think more clearly.

I then realised the desperate situation I was in. For a moment I was safe, but unless I could get into one of the boats, I was facing certain death, for there was not a chance in a thousand of being picked up by a passing ship. My predicament was not pleasant to contemplate, I visualised myself hanging onto the wreckage until, weakened by thirst and exposure, I would be unable to hang on any longer and eventually perish. With this thought in mind I strained my eyes to peer into the impenetrable darkness for sight of a lifeboat and hailed with all the strength my lungs would permit.

I could see nothing and although there were cries from others struggling in the water, no answering cry came from men in a boat. With a feeling of despair I realised that the strong current that was running had already borne the boats out of earshot. The cries of the others around me became less and less until all I could hear was the gentle lap of the water as I rose and fell with the slight swell of the sea. It must have been a couple of hours that I spent alone in the vast stillness of the ocean night with all hope of rescue abandoned before I made out the loom of a darkened ship making down towards me. After making all haste to hail her with the hope of being picked up, a voice in English called upon me to come alongside and I was hauled aboard to find my rescuers to be Germans and their ship a sea raider.

Contrary to the rough handling I expected, I was shown every care until a surgeon for wounds had examined me, and afterwards made as comfortable as could be expected with dry clothes, bedding and a smoke. Some of my comrades were already aboard the German ship when I was picked up and still others followed at intervals before the ship’s powerful engines broke into life and she raced away at full speed.

Out of the 165 people aboard the Gloucester Castle 41 survivors including 2 women and 2 children were taken aboard the raider. And to the outside world another merchant vessel had disappeared without trace. We had been sunk and taken prisoner by the famous German Raider 28 of which little was known at the time.

A vessel of some 6 thousand tons, she was, to all outside appearances a harmless merchant ship, but was actually a very heavily armed and efficient fighting ship.

In addition to several guns from four to six inch calibre and torpedo tubes, she carried a seaplane and could launch an M.T.B. All her armament was concealed cunningly in the mystery ship fashion, and, having a good turn of speed, she was engaged in the hit and run war against lone merchant ships.

The crew of this remarkable vessel, for the most part young men were very proud of their ship and their successes and seemed to entertain no fear of coming up against an Allies warship, in the event of which in any case they were prepared to fight. They took great care that we did not see too much of the secrets of the ship, at times blindfolding us if it was necessary to take us from one part of the ship to another. But in spite of all precautions, many of us saw much and could have disclosed plenty had we regained our freedom.

We learned from the German seamen that they picked up their victims during the day by a good system of masthead lookouts, followed them hull down until nightfall and then raced up on them and attacked without warning at point blank range, afterwards taking aboard all survivors as prisoners and leaving no trace of the action.

With grim irony they would inform us beforehand that they were going to attack and sink another unsuspecting victim at victim at nightfall. And so with nerves tensed and a feeling of helplessness towards the coming cold-blooded attack on our comrades we would wait, shut up below decks, for the crash of guns to announce the opening of the murderous assault, which, in each case was of short duration and resulted in the loss of the ship with more than half her crew.

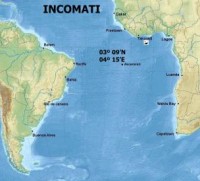

In three successive nights she sank three allied ships, following up her attack on the Gloucester Castle with the American tanker William S Humphreys the next night and a Norwegian tanker the following night. They were all night attacks and made without the slightest warning.

On each occasion before the ship went into action we were ordered to stand by with our life-belts on, and were assured by an officer who joined us below, that should anything happen to the ship he would see that every man got out on deck to take his chance, and that he himself would be the last to leave.

The ship’s success as a raider depended on the surprise attack, and destroying her victims in haste, making away afterwards at all speed and leaving behind no evidence in the form of survivors to reveal her secret.

It would be unfair to say that the treatment we received while aboard the raider, and later aboard her supply ship was anything but decent and fair under the circumstances. They fed us well, clothed those who needed clothing and granted us any request within reason. We were allowed on deck for exercise, a sick parade was called each day and in the evening at roll call an officer would read out to us from the ship’s wireless press the day’s news. Sometimes he would remark with a smile that he did not expect to be believed, as it was German news.

For more than two weeks that lone raider, with a hundred or more prisoners aboard roamed the South Atlantic in search of further victims, and at the end of that time made a rendezvous with her supply ship the Sir Karl Knudsen transferring all prisoners except the more badly wounded who were kept aboard the raider under the care of the surgeon. The supply tanker lay off from the raider hove to at about a quarter of a mile distant. We were taken across to her in a motor launch, and escorted by an officer from the raider.

This officer informed us, before wishing us goodbye and departing to his own ship, that though we would not be so comfortable aboard the tanker we should have the consolation of knowing that we would be put ashore as soon as possible. Whatever discomfort lay before us in the tanker, we were ready to accept it in preference to remaining aboard the raider in constant danger of being shot to pieces by one of our own warships, which at any time she was likely to come up against. Aboard the tanker we should have no such fear, for she was unarmed and could not show fight if she was run down. The worst we anticipated was having to jump over the side if an allied warship met up with her for we felt sure that in the event of such a thing happening, the Germans would scuttle her ship.

The story of the ‘Altmark’ came back to all of us when we found ourselves put down the hold of the tanker. Our conditions were very similar, over a hundred and fifty British, American, Norwegian and Chinese seamen crowded together in a steel box of space not more than forty feet square. In this condition we were destined to spend eight weary weeks at sea. It was anything but comfortable, insufferably hot in the tropics and cold and damp in other latitudes.

But again in fairness to the enemy they did their best under the circumstances to lighten out suffering. Bedding of a kind was provided, the food was reasonable and cigarettes and tobacco were issued regularly. In the lower latitudes when it became extremely cold, a tot of rum was issued to each man daily, and what extra clothing was to be had was given to those most in need of it.

Nazis these men might have been, but they were also seamen, and among seamen of all nationalities there exists that chivalrous code of the sea which these men, although our enemies, found it hard to ignore. Our surviving passengers had also been put aboard the tanker, and although we were not allowed to communicate with them, we had every reason to believe they were well treated.

In August while still in the South Atlantic, a rendezvous with the other operating raider 23 and a further fifty prisoners joined us, being the crew of the British ship Dalhousie sunk by 23. Once again before leaving the Atlantic the Sir Karl Knudsen met up with raider 28. And from the sole survivor we learned of another British ship being sent to the bottom by her guns.

The tanker had now exhausted her supplies and was ready to run into port to replenish them and put ashore her prisoners. What was to be her destination? Surely, we thought, some port in the South of France or perhaps even Germany itself. Great was our surprise when she headed south, rounded Africa well down, and then stood up towards the Indian Ocean.

On the 30th September, after most of us had been at sea for close on three months without sight of land, the Sir Karl Knudsen put into Singapore, and we realised the worst when we were told that we were to be handed over to the Japanese. This was the unkindest cut of all and absolutely unpardonable.

Fifty seamen, myself included were landed in Singapore, while the remainder of our comrades were kept aboard the tanker and taken on to Japan.

During the three years we remained on Singapore as prisoners, our thoughts often went to those sea raiders lurking in the Atlantic and taking their deadly toll of allied ships.

We consoled ourselves with the knowledge that their presence must be known or suspected, and it would only be a matter of time before the large force of the allied navies hunted them down and destroyed. The existence of the sea raider is a lonely, hazardous and precarious one. For a short while if the luck of the game is with him he can wreak destruction on his enemies. Unlike the submarine, he is unable to hide from his far superior enemies who are hounding him down, and for all the vastness of the ocean he is in an inescapable trap, and his ultimate destruction is inevitable.

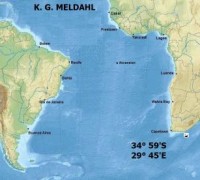

It was with considerable joy that we heard upon our release from captivity that in October 1943 the trap had closed in on ‘28’ and her career brought to an end when she was blown apart by four American torpedoes launched by the US submarine ‘Tarpon’.

Having the experience of being prisoners under both the Germans and the Japanese, my surviving shipmates and I know of the striking comparison between being treated by the one enemy as a prisoner of war, and by the other as a slave and a dog, to be kicked and beaten by a lot of savages.

We cannot forget or forgive the manner in which the Germans sank our ship, it may perhaps have been cowardly and treacherous but with the power of wireless to endanger their own safety they may have been left with no choice in their method of attack.

Pirates, yes. Murderers perhaps, but in view of the odds against them the courage of the lone sea raider must rate second to none.

Frank Chadwick 1945.

Frank Chadwick

By https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/76/a3858276.shtml