BRAZIL. THE HARD ROAD TO WAR * - THE HARD ROAD TO WAR

10)THE CRISIS RESOLVED

THE CRISIS RESOLVED

President Roosevelt left Washington for Hyde Park on Thursday, 29 May, without having made a final decision as to the immediate course that the United States should follow to combat the Nazi menace in the Atlantic. Eight days later, on 6 June, he announced to Secretaries Hull, Stimson, and Knox certain vital decisions, both as to what should be done in the Atlantic and as to the reinforcement of the Atlantic Fleet. The most significant of these decisions was that American troops should be sent as soon as possible to replace British forces then occupying Iceland.

Before announcing his decisions, which fixed a line of action that, for the time being, excluded the possibility of sending an expeditionary force to the Azores, the President had on 4 June approved the Azores plan. But it was a qualified approval, for at the same time he directed the armed forces to prepare an alternate plan for an unopposed garrisoning of the islands. Before taking this action, the President had received word through the Navy that, although the Azores had been substantially reinforced by troops from Portugal, these forces and the Portuguese Government would probably welcome an American occupation if the Germans invaded Portugal itself. Also, at the President's suggestion, the Department of State had invited Brazil to contribute a token force to any expedition that might be sent either to the Azores or to the Cape Verdes.

On the same day that the President approved the Azores plan, Under Secretary of State Welles presented him with information that would in all probability have postponed American action in any case. On 30 May Mr. Churchill had informed the President that Great Britain was prepared to occupy the Cape Verde Islands, Grand Canary, and one of the Azores, should the Germans march into Spain. The Prime Minister had stated then that he would welcome American collaboration in the occupation of the Azores.

On the same day Portugal informed Great Britain that while it might accept the aid of its British ally it did not want that of a nation with which it had no existing political commitments. The President's address of 27 May, said the Portuguese ambassador to London, had alarmed Portuguese public opinion, and Prime Minister Salazar felt that any invitation to the Americans would have to be deferred. The British therefore suggested to the United States on 2 June that it bow out of the Azores picture for the time being.

The Iceland decision had more of a political than military background, although it grew out of the commitment in the ABC-1 plan that, if the United States joined in the war, American troops would be sent to relieve the British garrison there, though not before 1 September 1941. As of 22 May, the Navy wanted to drop this commitment, and at the end of the month the Army proposed that the British be asked to release the United States from it. Army planners held that Iceland had little strategic value as an outpost from which to defend the Western Hemisphere.

But Iceland did have great strategic value for the defense of the British Isles and the North Atlantic seaway. After the British and Canadians extended their escort system across the Atlantic in the late spring of 1941, Iceland served as a much needed intermediate naval and air base. In the President's speech of 27 May he had taken the position that successful hemisphere defense depended upon the salvation of Great Britain and its oceanic life line across the North Atlantic. From this broad point of view both friendly control and effective military use of Iceland were vital to the national security of the United States.

On the eve of his unlimited national emergency address, President Roosevelt had approached Mr. Churchill on the subject of Iceland, and on 29 May the Prime Minister responded that he would cordially welcome an immediate relief of the British forces there. On 30 May the United States Ambassador to Great Britain, John G. Winant, arrived in New York to make a personal report on the situation and also to deliver to the President some confidential papers addressed to him by the Prime Minister. The ambassador was told by telephone from Hyde Park to go on to Washington and stay at the White House.

Mr. Winant subsequently told Secretary Stimson that the two principal objectives of his visit were, first, to make sure of the safety of convoys of foodstuffs and munitions to Great Britain and, second, to arrange to have United States naval strength on hand in the North Atlantic "when the attack is made on Great Britain later on by way of invasion." From Mr. Churchill, the ambassador brought specific requests for an extension of American naval activity in the North Atlantic and for American troops to replace British forces in Iceland.

On Monday afternoon, 2 June, Mr. Harry Hopkins (who then resided in the White House) asked Secretaries Stimson and Knox to join him in a discussion of the British situation and the steps that the United States ought to take to remedy it. One can only surmise that Mr. Winant may have already intimated to Mr. Hopkins the contents of the report and messages that he had brought from London. According to Secretary Stimson's record of this meeting, the discussion turned to a consideration of "further and more effective means of pushing up the situation, particularly by action in the northeast." Secretary Knox suggested American action with respect to Iceland, and both Mr. Stimson and Mr. Hopkins heartily concurred in the suggestion.

According to the Secretary of War, General Marshall also indorsed it immediately after the White House conference. At the War Council meeting the next morning, Mr. Stimson asked General Marshall to investigate the "possibilities in case we take vigorous action in the Northeast," by which he meant sending an expeditionary force to Iceland. Later on the same day, Mr. Stimson and Mr. Knox met with Secretary of State Hull and were at least partially successful in persuading him to support the Iceland project. After this meeting, General Marshall delivered to Mr. Stimson a staff report on the relative merits of an Iceland, as against an Azores, operation and expressed his preference for the former.

President Roosevelt returned to Washington on 3 June, and at noon Mr. Winant joined him to deliver his report and the messages from Prime Minister Churchill. After discussing matters with the ambassador, the President indicated his tentative approval both of the Iceland proposal and of more vigorous American naval activity in the North Atlantic. On 4 June the Army planners were told to prepare a plan for the immediate relief of the British forces in Iceland. It was at once clear to them that there was not enough shipping to carry out the Azores and the Iceland operations simultaneously.

Three days later the Army suspended its planning and preparations for an Azores expedition. The investigation of Army capabilities quickly convinced the President that the Marine Corps would have to contribute the initial contingent even for Iceland, and on 5 June he directed Admiral Stark to prepare a reinforced Marine brigade for dispatch to Iceland within fifteen days. On 6 June the President confirmed his decision to send a United States force as soon as the Icelandic Government requested American protection, and he tentatively decided also to order the transfer of a second quarter of the Pacific Fleet to the Atlantic.

These decisions in all probability reflected the President's new conviction that the Nazis were preparing to launch an all-out attack against the Soviet Union. Ambassador Winant told the President that before he left London British Intelligence sources had indicated the likelihood of a Nazi-Soviet struggle. During the first week of June the Department of State likewise received what Secretary Hull has called "convincing cables" from its representatives in Bucharest and Stockholm asserting that the Germans would invade the Soviet Union within a fortnight.

Should these reports be true, the United States could act with comparative safety along very different lines from those proposed during late May. It need no longer fear an immediate German drive toward the South Atlantic, and it probably could take much more forceful action in the North Atlantic without risking German retaliation or open involvement in the war.

While Secretary Stimson strongly favored an Iceland expedition as well as other vigorous lines of action in support of Britain, the Army planners would have much preferred to have nothing to do with expeditions either to Iceland or to the Azores. As late as 6 June, they were composing strong arguments against an Azores expedition, but they would have preferred an Azores to an Iceland operation.

With the GRAY plan suspended, War Plans chief Brig. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow on 19 June characterized the proposed Iceland expedition as "a political rather than a military move," and asked General Marshall to try to persuade the President to call it off. General Gerow believed that it was impracticable at this time for the Army to engage in any operations "which might involve engagements with the German forces," and he and his staff were therefore opposed to any movement of Army forces outside the Western Hemisphere.

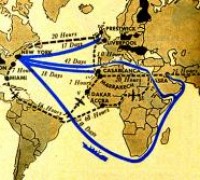

No matter what else was done, both Secretary Stimson and the Army General Staff also wanted to move a small security force (about 9,300 troops and 43 planes) to northeastern Brazil as soon as possible. On 17 June General Marshall pointed out to Under Secretary Welles that, as of 10 June, there was not a single American naval vessel within 1,000 miles of the eastern tip of Brazil, and no United States Army forces within twice that distance.

In an estimate submitted to General Marshall on 18 June, G-2 expressed its belief that the German push southwestward had reached ominous proportions: ten thousand Germans were believed to be in Spain; it was "reliably reported" that the Germans had concentrated transports in southern French ports ready to move four divisions to Portugal; German artillerymen, equivalent in strength to two regiments, were believed to have moved into Spanish Morocco; and G-2 was certain that German submarines were being supplied from the Canaries, and probably from French West African ports as well.

If this G-2 estimate were anywhere near accurate, it certainly behooved the United States to take some sort of quick action to protect the Brazilian bulge. This was the view presented by Secretary Stimson and General Marshall to the President in a bedside conference on 19 June, and the President told them he would direct the Department of State to find ways and means of getting American troops into Brazil. The day before this conference with the President, the Secretary of War had received some "very upsetting news" to the effect that the tentative decision to reinforce the Atlantic Fleet had been reversed.

Mr. Stimson drafted a protest to the President, stating "we are confronted with the immediate probability of two major moves in the Atlantic [Iceland and Brazil] without sufficient naval power there to support them." Continuing, he wrote, "The menace of Germany to South America via Dakar-Natal requires that the hold by American sea-power upon the South Atlantic should be so strong as to be unchallengeable.

Although Secretary Knox shared Mr. Stimson's views on the question of Atlantic Fleet reinforcement, the President was impervious to the Secretaries' pleas. On the other hand, at the 19 June conference the President asked Mr. Stimson and General Marshall whether the Army could immediately organize an expeditionary force of 75,000 men for use in several theaters-Iceland, the Azores, the Cape Verdes, or elsewhere.

In effect the President was told that, because of legislative restrictions on employment of Reserve and National Guard troops outside the Western Hemisphere, this could not be done without completely destroying the efficiency of all Army combat units. Aside from that, the Army had neither the equipment nor the ammunition available to mount such an expeditionary force and still leave anything for the Army units remaining to defend the continental United States. In short, at the time Germany attacked the Soviet Union, the United States Army's offensive combat strength was still close to zero.

On the eve of the invasion of the Soviet Union a German submarine almost precipitated open war with the United States by chasing and trying to attack the battleship Texas. and an accompanying destroyer southeast of Greenland and within the war zone that the Germans had proclaimed. The U-203 trailed the Texas. and the destroyer on the night of 19-20 June for about 140 miles but could not launch its torpedoes because of poor weather conditions and the evasive action of the American ships.

After the sinking of the American freighter Robin Moor in the South Atlantic a month earlier, Hitler had forbidden further attacks on United States merchant and naval vessels outside the war zone. When he learned about the Texas incident on 21 June, Hitler, in order to prevent incidents that might bring the United States into the war, directed the German Navy to stop all attacks on naval vessels in the North Atlantic war zone until after the Eastern Campaign was well under way. The Germans invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941.

The next day, in a letter to the President, the Secretary of War called the event "an almost providential occurrence." In the letter Stimson stated that he had met with General Marshall and his War Plans staff, and they had estimated that the Germans would now be thoroughly occupied in the Soviet Union for a period of from one to three months. While so involved, the Germans could not invade Great Britain, nor could they attack Iceland or prevent American troops from landing there.

The Germans would also have to relax their "pressure on West Africa, Dakar and South America." The General Staff officers with whom Mr. Stimson had consulted were unanimously of the opinion that the United States ought to take advantage of this golden opportunity "to push with the utmost vigor our movements in the Atlantic theater of operations." Secretary Stimson interpreted this to mean the execution of the Iceland project, American naval reinforcement in the Battle of the Atlantic, and the movement of American security forces to Brazil.

War Department officials, military and civilian, were undoubtedly united in the opinion that the United States ought to act with vigor during the period that Germany was heavily involved in the Soviet campaign, but the new war outlook had not wrought any miraculous change in the Army's very limited means for action. A June estimate of Army capabilities, under preparation since late May but adjusted to take the German attack on the Soviet Union into account, concluded that the United States could not for many months do much more than conduct "a citadel defense of the Western Hemisphere including the line Greenland, the Atlantic bases, Natal, the Amazon Valley, Peru, Hawaii, and Alaska."

Beyond that, it could probably carry out its ABC-1 commitments to England, including a "subsequent" complete relief of British forces in Iceland. Similarly, it could carry out a limited reinforcement of the Philippines. The United States probably could land holding forces in the Azores, but it probably could not occupy and hold any of the other southern Atlantic islands or any foothold on the western coast of Africa.

In time, the United States might accumulate sufficient military strength to secure southern South America. In the still more distant future, it might be able "to take action against our main enemies in Europe." Army planners under the circumstances would have preferred to limit immediate Army action in the Atlantic to the dispatch of security forces to Brazil. In spite of the Army's prime interest in Brazil, the plan to send troops there ran into various snags that prevented any action for the time being other than the initiation in July of formal Brazilian-American joint staff planning.

With a different point of view from that of the Army planners, Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy urged Mr. Stimson to concentrate Army action toward what he termed the main strategic area of the war--the British Isles, and their North Atlantic approaches. To gain control of the northern and southern flanks of these approaches, he advocated placing troops in both Iceland and the Azores before undertaking any Brazilian operation.

"The focus of the infection lies to the northeast," he wrote. "With that insulated, South America presents no problem." Although the Army's lack of readiness made it hesitant to advocate measures that would lead to open involvement in the war, the United States Navy was ready to take the risk. Two days after the Germans launched their new attack, Admiral Stark went to the President and urged him to approve the immediate assumption by the American Navy of convoy responsibilities in the North Atlantic.

The Chief of Naval Operations recognized that this step would almost certainly involve the United States in the war, but he considered "every day of delay in our getting into the war as dangerous, and that much more delay might be fatal to Britain's survival." Only a war psychology, Admiral Stark believed, would speed war production and thereby permit the United States to initiate decisive measures in the Atlantic. President Roosevelt at first leaned toward the Navy's school of thought. He had no intention of dropping the Iceland project, and on 1 July, when the Icelandic Government agreed to the terms upon which American troops were to be received, the President ordered the initial Marine contingent to sail.

On 2 July, he tentatively approved a new Navy plan for North Atlantic operations (Navy Western Hemisphere Defense Plan No. 3) that would have involved American naval escort of all sorts of shipping from the Halifax-Newfoundland area to the longitude of Iceland, to start as soon as American forces landed in Iceland. On 5 July the President told Mr. Stimson that he was again planning to order a second increment of the Pacific Fleet into the Atlantic to implement this Navy plan.

But when it became clear that the Japanese had decided to continue their southward advance the President for the second time postponed naval reinforcement of the Atlantic and instead instructed the Navy to adopt a more modest projection of its current North Atlantic activities. The Navy thereupon put into effect its Western Hemisphere Defense Plan No. 4, which provided specifically only for the escort of United States and Icelandic shipping to and from Iceland. The real impact of the German invasion of the Soviet Union on the security of the Western Hemisphere derived not from the immediate but from the longer range development of the situation.

Instead of a breathing space of one to three months duration, the United States and the rest of the New World were to be free henceforth from any great danger of German surface or air aggression in the western Atlantic. The Nazi-Soviet conflict had a contrary effect in the Pacific. Japanese decisions and actions from early July 1941 onward showed that the Japanese also considered this conflict a "providential occurrence," and they proceeded to take full advantage of it by pushing the erection by force of a "Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere" with all speed. The United States in consequence was to be brought fully into the war not as a result of measures taken to combat the Nazi menace in the Atlantic, but by Japanese aggression in the Pacific.

Transcribed by Patrick Clancey. HyperWar Foundation