ASCENSION ISLAND AND THE SECOND WORLD WAR - ASCENSION ISLAND IN THE WAR

4)SUMMER OF 1942

BY DAVID FONTAINE MITCHELL

During the summer of 1942, the Engineers constructed a mess hall, two radar stations, several medical facilities, and a command complex. The command complex, which became known as “Command Hill,” was erected with tiles imported from Recife and situated so that it provided a panoramic view of the island. The sanatorium became known as the 175th Field Hospital and was established near the base of Green Mountain, nearly 1,000 feet above sea level. The location was ideal for patients due to its cool climate, up to 15 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than the rest of the island. Roughly four miles from both Georgetown and Camp Casey, the sanatorium was also established as a “last stand area” in case the island was ever attacked. There was a cache of food and water at the site to provide for the soldiers should they have to retreat inland from the threat of potential occupiers. The other buildings consisted of a medical administration building, a surgery building, a supply building, and three wards for housing patients.

The enlisted men stationed at the sanatorium would deal with a wide range of casualties during their extensive stay on the island, including routine illnesses, fatigued sailors rescued from sea, and victims of plane crashes. Soldiers assigned to the 175th attended conferences and classes throughout the war in order to keep them prepared for various potential catastrophes, including a possible chemical attack. Roughly 3,000 people were treated at the hospital during the first two years after it opened.

Pipelines were established in order to link the island’s fuel tanks with the tanker ships offshore. The main sea pipe was laid on 3 June in an area known as Clarence Bay, an operation that required the assistance of nearly every person serving on the island at the time. The pipe was 1,100 feet long and had to be dragged into the sea by hand. Buoys were attached to the pipeline to keep it afloat before it reached the offshore tanker, at which time the buoys were shot at from a distance and sunk, establishing the connection nine fathoms undersea. The pipe was then connected to the tank farm, which would provide fuel for the aircraft that would soon be landing on the island.

The Engineers were making good progress, and by mid-May the airfield was already three quarters of the way completed. Washington was informed on 12 June that the runway was advanced enough to receive aircraft, although construction was not yet completed. The first landing, an unofficial one made by a British Fairey Swordfish plane, came just three days later, on 15 June. Royal Navy pilot Lt. E. Dixon-Child had taken off from the HMS Archer and was searching for survivors of the nearby torpedoed SS Lyle Park. Dixon-Child’s orders also included dropping a message onto Ascension to be relayed by C&W to the Admiralty in London, but when he flew over the island he was surprised to see the airfield and decided to land.

The pilot, planning to simply land and deliver the note, was met with machine-gun fire from the 426th. Three bullets hit the plane and a fourth hit the pilot’s shoulder harness. Luckily the aircraft was identified before it suffered any significant damage, and Dixon-Child was cleared to land. Shortly after the message for C&W was delivered, the plane was back in the air and returning to the Archer. Construction of the runway, 6,000 feet long and 150 feet wide, was completed in only 91 days. Soldiers had worked around the clock to finish the job by their imposed deadline; in the process, they had used roughly 13,000 blasting caps and over 35 tons of explosives to remove over 380,000 cubic yards of rock.

Air transport Command mechanics work on an engine. The National Archives.

The airfield officially opened on 10 July with the arrival of the first American plane, a Consolidated B-24 Liberator by the name of Our Kissin’ Cousin en route to Natal from Accra. This was followed 10 days later by 14 American ferry planes en route to West Africa from Natal. By the beginning of August, 126 planes had landed on Wideawake Field. The first Royal Air Force Ferry Command aircraft, a Martin B-26 Marauder, landed on 6 August on its way to Accra. The first Pan American Airways plane, a Douglas C-54 Skymaster contracted to the U.S. Army Air Force’s (USAAF) Air Transport Command, arrived roughly three months later on 16 November. The airfield was restricted to military use only; only in case of an emergency would a commercial aircraft be permitted to land.

The location of the airfield was critical for ongoing military and logistical operations in Africa because it served as a refueling station for multiple aircraft taking off from Brazil that would have otherwise been unable to make the transoceanic journey. Often, an aircraft’s passengers would stay overnight prior to departure in the morning; however, it was not uncommon for the layover to last only 40 minutes, just enough time for the plane to refuel while the personnel got something to eat at the nearby mess hall. Anti-submarine patrols originating from Natal would stop over on Ascension to refuel before returning back to their home base. At the time, it took roughly six hours for aircraft departing from Natal to make the 1,248-mile journey to the island. A famous quote espoused by pilots at the time was, “If we don’t hit Ascension, my wife gets a pension.”

Although the airfield was located in the most ideal location on the island, pilots were still advised to take caution when landing and taking off from the runway. One danger came from the numerous wideawake birds, which could potentially get caught in aircraft engines or break a window during takeoff or landing. On a couple of occasions, the airfield was forced to temporarily shut down for hours at a time during the height of the birds’ breeding season. Also, the end of the runway was scattered with numerous sharp volcanic rocks that could greatly harm a plane that accidentally overshot. Plans to extend the runway by an extra 700 feet began on 12 November 1942 and were completed on 5 February 1943; however, on 15 December 1943 a B-26 Marauder crashed into the rocks during takeoff. The plane exploded into flames, resulting in the death of all three people onboard.

Soldiers attend a Memorial Day service at the American cemetery. Col. J.C. Mullenix collection, Ascension Island Heritage Society.

On 14 August 1942 the transport ship USAT James T. Parker arrived at Ascension accompanied by two freighters, one cruiser, and one destroyer. The fleet was transporting the island’s main occupying force, the 91st Infantry Regiment, along with a new medical unit and the 28th Coast Artillery. Accompanying them were several anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns, as well as three machine guns designated for each potential landing point on the island. While the men were unloading the supplies brought by the vessels, three Navy PBY Catalina maritime patrol aircraft surveyed the area for enemy submarines. The 91st Infantry was under the command of Col. Ross O. Baldwin and consisted of roughly 2,000 enlisted men and 138 officers. On 17 August Col. Baldwin assumed command of all U.S. forces on Ascension. Two days later the majority of the 38th Engineers departed for the Congo, where they had been tasked with the construction of another airfield at Leopoldville; however, the original medical contingent remained permanently stationed at the field hospital.

A total of 203 men of the 38th remained on the island and formed the 898th Engineer Aviation Company while the 28th took over the 5.5-inch guns from the 426th. The 91st initially tasked two companies with the island’s defenses: K Company was responsible for the north (Northeast Bay, English Bay, and Comfortless Cove) and M Company was responsible for the south (Long Beach, South West Bay, Mars Bay, and Gannet Hill). The men of the AVDF were later assigned to the anti-aircraft guns that protected the Georgetown settlement. A daily newssheet began publication on 21 August, providing news from around the world to those stationed on the island. Originally titled “The 877 News” after the Army Post Office number for Ascension, the newssheet was renamed “The Wideawake News,” until 15 January 1943, when the American Censorship authorities changed the title to “The Daily News” for security purposes. A few months later the name was changed again to “Task,” which managed to stick for the remainder of the war. The 91st experienced their first mishap on 28 August 1942 when a group of servicemen accidentally fired upon an operator tending to a water distillation unit. The operator approached the unit at night using a flashlight, which must have been highly uncustomary because he soon found himself under fire. Luckily the man survived the ordeal unscathed, as roughly 40 shots were fired upon his location before he was identified.

On 3 September the men again accidentally fired upon a friendly target, and again luckily failed to inflict any substantial damage. A P-39 experienced a fuel system failure shortly after taking off from Ascension and was forced to make an emergency landing in the ocean. The island’s gunners were caught by surprise when they witnessed an unexpected object on the horizon. Believing the object to be an approaching enemy submarine that signaled a coming attack on the island, the gunners opened fire. The lieutenant piloting the aircraft managed to survive the ordeal and was rescued by one of the crash boats assigned to the island after he was identified.

The garrison was again alarmed on 15 September when they were informed of multiple enemy ships operating within the area. Unbeknownst to the men on the island, the ships were responding to the nearby sinking of the RMS Laconia by U-156, which had occurred on 12 September. Werner Hartenstein, the German commander of U-156, had sunk the Laconia merely 250 miles from Ascension; however, when he discovered that the ship was transporting 1,800 Italian prisoners of war, Hartenstein immediately began a rescue operation, calling for diplomatic neutralization and pledging not to harm any Allied ships assisting in the area. Ascension was informed of neither the sinking of the Laconia nor the neutralization of the area and, after receiving intelligence that U-boats were operating nearby, sent a B-24 piloted by Lt. James Harden to inspect the site on 16 September. Harden discovered U-156 assisting lifeboat passengers and radioed back to the island for orders.

Still unaware of Hartenstein’s neutralization of the area, Ascension instructed the B-24 to attack U-156. After leveling damage to the U-boat, the aircraft returned to the island, angering both Hartenstein and Rear Admiral Karl Doenitz who was in charge of all German submarine activity. In response to the attack, Doenitz ordered that all survivors be transported to Vichy French ships which were on their way to the area. The servicemen on Ascension, still unaware of what was going on, immediately came to the assumption that the French vessels were on their way to attack the island. On 17 September Harden was again dispatched to the site with his B-24, where he attacked U-506, although no damage was issued. Doenitz became so annoyed by Harden’s attacks that he issued the infamous “Laconia Order” that same day. The order instructed all Uboat commanders to avoid rescuing or assisting any survivors of shipwrecks no matter the circumstance. Later, during the Nuremberg War Trials, Doenitz was sentenced to 10 years in prison for the implementation of this particular order. Ascension was finally informed of the details of the rescue mission later the evening of the 17th, but by then it was too late. Despite the circumstances, over 1,000 people survived the Laconia incident.

Allied forces began to land in North Africa on 8 November, and many of the planes stopped on the airfield to refuel while en route. By mid-November, a directive had been issued warning naval vessels not to sail within 70 miles of Ascension unless routed to the island with prior permission. 24 November witnessed the island’s transfer of command to the U.S. Army’s South Atlantic Command, headquartered in Recife and overseen at the time by Maj. Gen. Robert L. Walsh. Over a year would pass before Walsh visited the island for an inspection on 24 December 1943. On 16 December 1942, four South Africans arrived on the island, having been contracted to work on the Royal Navy’s wireless telegraphy (W/T) installation plant. It was not uncommon for the Admiralty to contract constructional work out to West Africans and South Africans, who were transported to and from the island throughout the war as labor demands arose.

A baseball game in full swing. The National Archives..

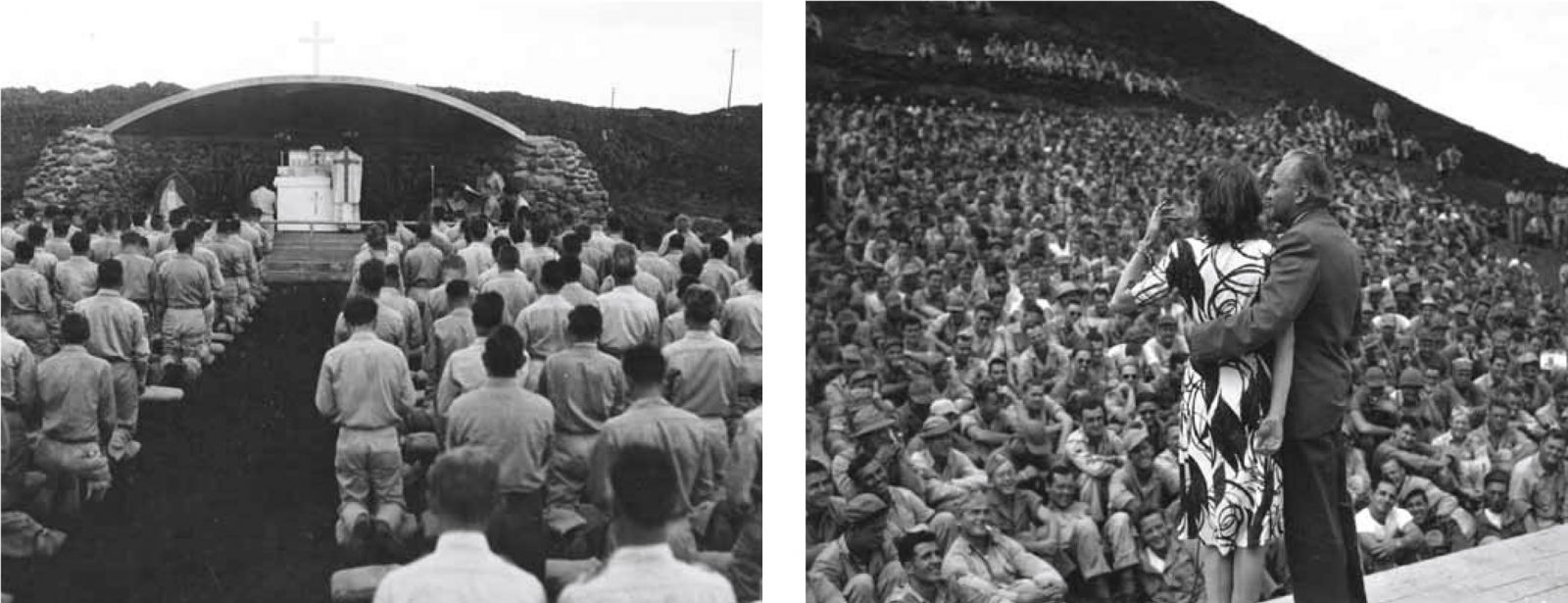

Catholic Easter service at the Grotto. The National Archives. USO performers at the “Bull Gang Theatre.” Col. J.C. Mullenix collection, Ascension Island Heritage Society.

Wideawake Field. The National Archives.

On 22 December, permission was granted for U.S. servicemen to use an area in the southeast section of the island as an air bombing practice range. As of 18 December, civilians working for C&W were prohibited from visiting the area during the week. Bombing practice ceased on 27 May 1943 and the area was reopened. Col. Baldwin was re-posted and U.S. forces on the island came under the command of Lt. Col. Russell B. Hathaway on 27 January. By now the airfield was witnessing considerable daily traffic, and at times up to 40 planes were situated on the runway. The AVDF was training successfully with U.S. forces and cooperation between units was reported as excellent. Roads were being constructed throughout the island, and by this point roughly half of those planned were completed. Large fish were also being caught with regularity off the shore, providing food for both the servicemen and the C&W employees.

February and March witnessed increased U-boat activity in Ascension’s surrounding waters—in one instance only eight miles offshore—forcing the command to issue island-wide blackouts on a couple of occasions. The enemy was still unaware of the ongoing Allied activity on the island, and the blackouts were issued to continue to shield the military’s presence. On 8 March the British South Atlantic Freight Service began to make stopovers on Ascension during its weekly flights to Accra. Canadian Royal Air Force Pilot-Officer F. S. Lamplough arrived on 14 March to assume command of British Ferry operations. March also witnessed the establishment of wireless communication with Accra, Robertsfield, and Natal.

Taking over from Hathaway, Col. J.C. Mullenix of the U.S. Cavalry assumed command on 1 April. Two days later members of the Royal Air Force began to arrive on the island. The RAF unit that eventually formed was tasked with operating a communications hub at the airfield later known as the “No. 90 Staging Post.” The post consisted of four officers (an operations officer, a signals officer, and two cipher officers), one sergeant cipher clerk, and 12 airmen (nine radio circuit operators, one cipher clerk, and two transmitter station operators). These men worked with the Americans in a joint U.S. Air Transport Command/ RAF Transport Command Operations building and oversaw numerous aircraft deliveries to and from the island.

In May a U.S. meteorological post was established in St. Helena to help better determine the weather forecasts for pilots flying in and out of Ascension. During this time, the soldiers on Ascension rescued several men who were stranded at sea—survivors of the nearby U.S. Samuel Jordan Kirkwood and Dutch Benakat wrecks—and treated them at the 175th Field Hospital. Survivors of the Benakat were subsequently picked up on 7 July by the HMS Corfu and transported to West Africa. As a result of these rescues, U.S. commander Mullenix requested an appropriate vessel to engage in rescue operations offshore. By the middle of May, the U.S. presence on Ascension had become public and the operation was no longer a secret. Although the world was now aware of the island’s activity, the secrecy ban was not lifted until 26 November. The North Africa campaign ended on 13 May and the Allies took control of North Africa, in part due to the refueling station strategically located on Ascension. The airfield continued to be of use following the Allied invasion of Sicily on 10 July, as aircraft maintained their regular stop-over on the island. Army Chief of Staff Gen. George Marshall landed on the island for a visit on 5 June while en route to the U.S. following a meeting in Algiers. Later on 25 July, 168 U.S. servicemen arrived as reliefs aboard the Gatun. This was coupled by the 12 September return of the Gatun, which brought 62 U.S. military police to the island.

Above left, survivors from U.S. Liberty ship Samuel Jordan Kirkwood. Col. J.C. Mullenix collection, Ascension Island and Heritage Society.

Seen right, survivors from Dutch merchant Benakat. Col. J.C. Mullenix collection, Ascension Island and Heritage Society.

Cont.