ASCENSION ISLAND AND THE SECOND WORLD WAR - ASCENSION ISLAND IN THE WAR

3)THE SECOND WORLD WAR

BY DAVID FONTAINE MITCHELL

THE SECOND WORLD WAR

War broke out in Europe in September 1939, and Ascension’s introduction to the latest conflict came just months later when, on 24 December, the island was approached by an unidentified submarine. The alarm sounded to warn the company of a possible attack; however, the approaching vessel turned out to be the HMS Severn stopping in hopes of gathering fresh fruits and vegetables. The Severn was returning to Freetown after an unsuccessful mission to locate the German oil tanker and supply vessel Altmark, which was in the South Atlantic in support of the notorious pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee at the time. The battleship had had a significant impact as a commerce raider in 1939, sinking nine Allied merchant ships in the Atlantic and causing considerable damage to Allied logistical operations. In recognition of the need to provide adequate security on the island, the Ascension Volunteer Defense Force (AVDF) was established in April 1940. Stephen Cardwell, C&W’s general manager at the time, was put in command of the small 27-person force, assisted by a group of NCOs and an officer of the Royal Artillery recently arrived from St. Helena.

Around this period, five radio operators from the Civilian Shore Wireless Service arrived on Ascension to man a high frequency direction finding (HF/DF) station, assisted by a 30-man Royal Navy detachment. These men were in charge of monitoring German naval radio frequencies in the area and relaying signals to their sister stations located in St. Helena and Freetown. The signals intelligence (SIGINT) collected was used to deter ongoing U-boat activity in the South Atlantic.

The defense of the island was strengthened roughly a year later in March 1941 with the arrival of a Royal Artillery detachment consisting of 44 servicemen. In addition, two 5.5-inch guns, previously removed from the HMS Hood (a vessel destroyed shortly thereafter by the German battleship Bismarck in the Battle of Denmark Strait on 24 May 1941) were brought ashore. The guns would come in handy later that year when the German U-boat U-124, commanded by Johann Hendrick Mohr, surfaced offshore.

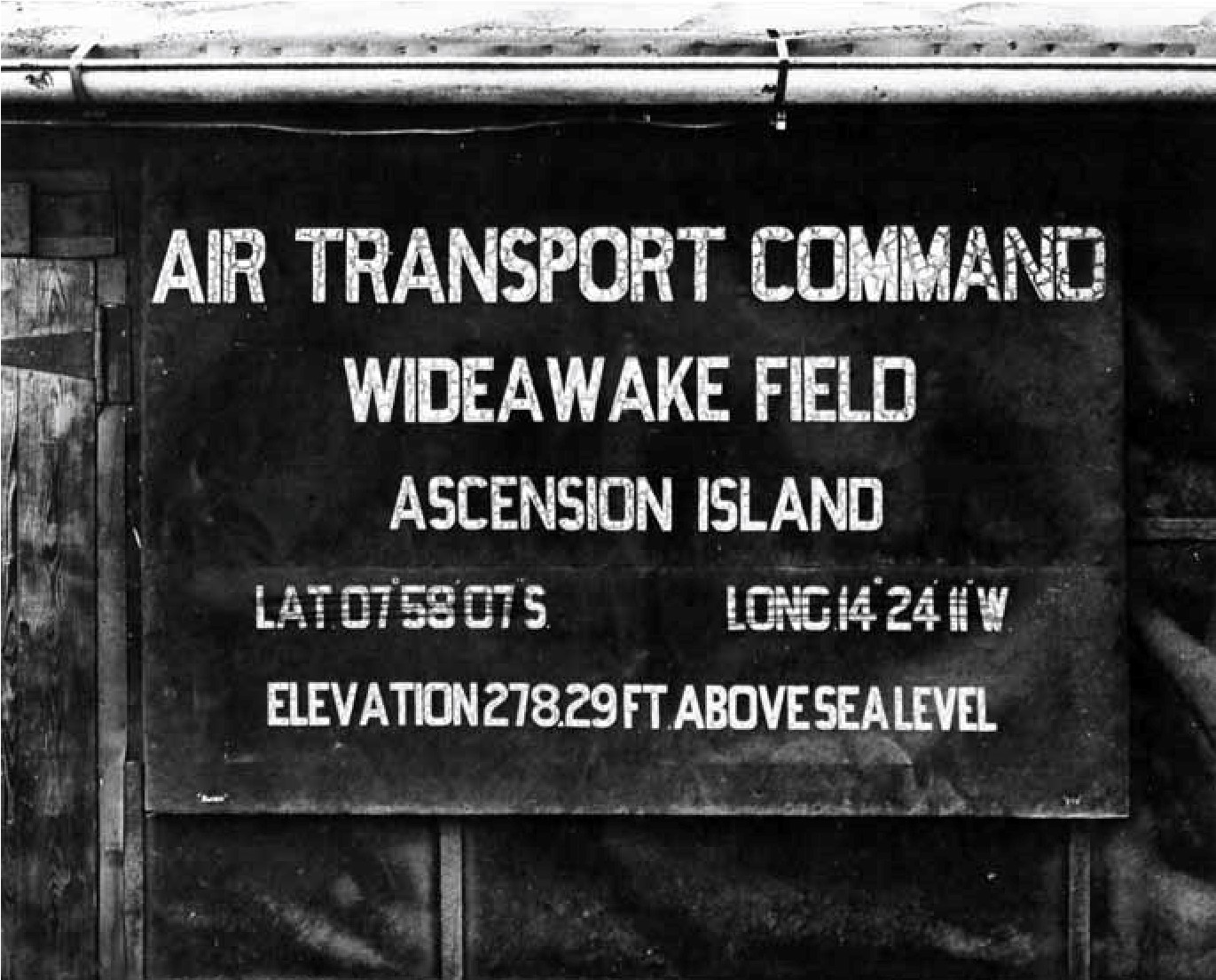

Sign at Wideawake Airfield. National Archives.

Mohr and the crew of U-124 were patrolling in the South Atlantic when, on 3 December 1941, they encountered the American cargo ship SS Sagadahoc south-west of St. Helena. The Sagadahoc was en route from New York to Durban when it was stopped and searched by Mohr’s men. Having discovered “contraband” in its cargo, Mohr decided to torpedo the 6,300-ton vessel after allowing the ship’s personnel to board its available lifeboats. This was the third U.S. merchant ship to be destroyed prior to the American entry into the war. Around this time, the British sank the German auxiliary cruiser Atlantis and the supply ship Python, neglecting to rescue the 414 survivors who were now stranded at sea. Four U-boats, including Mohr’s U-124, were forced to bring aboard all of these men during a rescue operation that commenced on 5 December; a daunting task for submarines not fitted for such a large number of passengers.

Mohr concluded that the only way to get these men to shore in France in adequate time was for the U-boats to navigate on the surface. In an attempt to convince British forces that the U-boats were maintaining operations in the South Atlantic despite the circumstances, Mohr attempted to attack Ascension from the sea at mid-day on 9 December, two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor and two days before Hitler would declare war on the United States. However, as soon as his U-124 was spotted, the men stationed at Ascension’s garrison fired upon Mohr with the guns provided by the Hood, forcing the vessel to make an emergency crash dive and flee the area. Although he failed to deliver any damage, Mohr’s plan ultimately proved successful. As a result of the attempted attack, British forces believed that the U-boats were still operating in the area, and Mohr was able to set sail for France, arriving shortly thereafter.[1]

[1] Mohr was later killed on 2 April 1943 when U-124 was sunk by the HMS Stonecrop and the HMS Blackswan west of Oporto, PortugaL

Rollers crash onto Ascension’s shore. Col. J.C. Mullenix collection, Ascension Island Heritage Society.

In November 1941 one month before the United States would officially enter the war—the governor of St. Helena relayed a classified message to Cardwell instructing him to survey Ascension for a site appropriate for building an airstrip. Cardwell was informed that the Americans would be involved in the process and was told not to discuss the plans with anyone. This was consistent with diplomatic negotiations between the U.S. and Britain that occurred in September 1940, granting the Americans the right to establish military bases in certain British territories in exchange for multiple naval destroyers. The U.S. was preparing to join the war effort and Ascension was to serve a vital purpose. Several British merchant ships had already been sunk in the Atlantic, and an airfield between South America and Africa would provide for both a refueling station for planes involved in logistical and combat operations and a staging base for anti-submarine raids.

After surveying the island, Cardwell settled on a location in the south-west known as Waterloo Plain, which would soon be transformed into “Wideawake Field” (named after the numerous sooty terns, also known as “wideawake birds,” that inhabited that area of the island). Cardwell noted that the site’s flat terrain aligned with the southeast trade winds made it an ideal location for an airstrip. He then compiled his observation into a report and sent it to the governor of St. Helena; however, he failed to receive a follow-up response or notification from the Admiralty. Ascension’s company manager had been told that he would be informed of when an American team would arrive for further inspection, and so he was understandably shocked when, with no prior notice, a battleship approached the island on 25 December 1941. (With this incident, and the Severn’s 24 December visit two years earlier, Christmas had become an eventful holiday for those stationed on Ascension since the start of the war.)

Given that Cardwell had received a classified directive to withhold information regarding the airstrip plan from those stationed at the garrison, his men were even more startled by the ship on the horizon. Poised to attack, they soon identified the incoming vessel as the American cruiser USS Omaha. On board was a reconnaissance team that had been sent from Brazil to inspect the potential location that Cardwell had recommended. Three Americans, led by Lt. Col. Kemp of the Army Air Corps, scrutinized the area for two days. The Omaha also dispatched a plane to conduct an aerial inspection. The American reconnaissance team’s preliminary survey concluded that the site was an adequate one for development, and shortly thereafter they sent their proposal to Washington. Although there were some disputes between the U.S. and Britain regarding the specifics of the operation, including post-war rights to the forthcoming airfield, the nations agreed to begin construction without delay.

The U.S. Army’s 38th Engineer Combat Regiment arrived at Ascension—which they dubbed “The Rock”— on 30 March 1942. Before them lay a daunting task: construct a fully operational airfield in less than three months. The regiment was less than a year old, having been activated on 28 May 1941, and consisted of a wide range of draftees hailing predominantly from the east coast. By the time of the unit’s formation at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, the “38th Engineers” consisted of roughly 1,300 servicemen. The men received orders in February 1942 that they would be deploying to an undisclosed territory called “AGATE,” which was a code-name for Ascension. Departing on 14 March, the Engineers boarded the Army transport ship USAT Coamo and the military freighters SS Luckenbach and SS Pan Royal.

They were accompanied by 154 men of the 426th Coast Artillery, 8 men of the 692nd Signal Corps Air Warning Detachment, a 77-person medical contingent, a 2-man postal section, a 9-man Army Airways Communication section, and ordinance, finance, and quartermaster detachments consisting of 14, 8, and 41 men respectively. Together these men comprised what was known as “Task Force 4612.” The Coamo and the Luckenbach were escorted to the South Atlantic by two destroyers, the USS Ellis and the USS Greer, and one cruiser, the USS Cincinnati. The Pan Royal sailed individually to the island unescorted while the main fleet stopped over in Recife to refuel before embarking toward Ascension, where they would change the dynamic of the island forever.

The task force spent the first 27 days just unloading the massive amount of equipment—8,000 tons of it—they had brought with them. This work was made more difficult by the island’s notorious rollers— massive waves from the west that can reach up to 10 feet in height at unpredictable times. The Engineers encountered multiple other setbacks during the early phases of their operation: two men drowned and another was electrocuted, one soldier was killed when he fell off a bulldozer and the vehicle ran over him; several others contracted dysentery, from which they later recovered. A supply ship once failed to arrive and rations ran low, forcing the men to fend for themselves by catching porpoises, turtles, tuna, and whatever else the sea provided. Rations had to be cut on two separate occasions, resulting in weight loss and fatigue among the men. The 38th managed to overcome these obstacles, however, and embarked upon an engineering marvel that many believed would be impossible to achieve.

5.5 inch guns provided by the HMS Hood. Col. J.C. Mullenix collection, Ascension Island Heritage Society.

Col. Robert E. Coughlin was the initial commanding officer in charge of U.S. military activity on the island. He was assisted by battalion commander—and future Chief of Engineers—Maj. Frederick J. Clarke.[1] The men were joined by administrative officer Col. James N. Tomlinson on 10 May 1942, who had been appointed by the Colonial Office to serve as a liaison between the Americans and the C&W workers. Tomlinson was also the appointed government representative to St. Helena, and therefore responsible for maintaining regular communication between the two islands. The Royal Artillery departed Ascension for St. Helena on 25 April following the transfer of the island’s defense to the United States military. Prior to their withdrawal, all guns and ammunition on the island were handed over to the U.S. forces. The Royal Artillery had been manning the 5.5-inch guns, and upon their departure the 426th took over the responsibility. Although the Artillery left, the Royal Navy remained, tasked with the administration of an HF signals station located in Georgetown. The AVDF also continued their presence on the island; however, they immediately came under the command of U.S. Forces.

Ascension’s unique terrain required the Engineers to be both innovative and experimental. Since the island’s water supply was limited, the men first assembled sea-water purification units, coupled with makeshift water tanks for drinking and cooking. The initial water ration was only five gallons per week for each soldier, upon the arrival of more units, this was increased to four gallons per soldier per day. The men were forced to bathe themselves, wash their clothes, and clean their mess kits using the salt water provided by the ocean. During construction of the airfield, a lack of sand and stone typically needed for pavement required the men to utilize what the island had to offer— volcanic ash and rock—mixed with water transported throughout the day and night from the ocean to the construction site. The Engineers also utilized the guano left by the island’s birds; this was made into bricks to be used in the construction of buildings. The operation proceeded 24/7; at night the soldiers would work under camouflaged lighting systems that shielded their activity from enemy ships at sea, as the construction of the airfield was still extremely secret.

The U.S. and Britain went to great lengths to ensure the confidentiality of the island base. Strict censorship rules were established on Ascension, and all outgoing messages had to first be approved by the authorities. Telegrams were marked as if they were sent from Cape Town, and personnel stationed on the island were instructed not to speak of ongoing activity with anyone. Administrators of West African colonies were instructed not to publish any stories or reports referring to American activity on the island in their territories. Both American and British servicemen stationed on the island were prohibited from disclosing their location to anyone, and C&W workers were barred from discussing ongoing activity on the island with outsiders. In order to deter leaks of any kind, the C&W manager was instructed to censor all telegrams sent by his staff. In the case of a mail ship arriving prior to censorship, all letters were placed in a separate bag marked “Ascension Mail – Uncensored” to be reviewed by the British Censor in London.

The men of the 38th worked on four separate tasks at the start of the operation: 1) the formation of a camp site adjacent to where the airfield was to be built, 2) the arrangement of an area to hide and store aviation fuel tanks, 3) the construction of a road to transport supplies from Georgetown to the site, and 4) the establishment of a hospital for the medical contingent to work out of. The camp, named Camp Casey after Army engineer Maj. Gen. Hugh John “Pat” Casey, was completed on 20 April. Although the airfield was impossible to shield, the men were successful in camouflaging the eight steel fuel tanks that held 462,000 gallons each and the bomb-storage building with netting and rock so that they wouldn’t be spotted from the air. Throughout the heat of those early days, the men of D-Company laboriously worked on the road, which thereafter became known as D-Co Road.

[1] Clarke would later discuss the 38th’s mission after it had become public in a 1944 National Geographic article entitled “Ascension Island, An Engineering Victory.”

Cont.