ASCENSION ISLAND AND THE SECOND WORLD WAR - ASCENSION ISLAND IN THE WAR

1)ASCENSION ISLAND IN SECOND WORLD WAR

BY DAVID FONTAINE MITCHELL

In March of 1942, one of the most remote islands in the world received a visit from the United States military. Situated in the South Atlantic, the island’s existence was largely unknown, and both the U.S. and Britain wanted to keep it that way. A secret airfield was constructed by the 38th Engineers within the first 90 days of their arrival, and from thereafter aircraft taking off from Brazil had a place to refuel on their way to Africa, the Middle East, and the China-Burma- India (CBI) Theater of operations. The island also contributed greatly to antisubmarine patrols in the South Atlantic, deterring U-boat activity across the region. Sadly overlooked by most history books and documentaries, this tiny landmass proved vital to the Allied campaign throughout the Second World War. This is the story of Ascension, truly “one of the strangest places on the face of the earth.”

.png)

THE ISLAND'S EARLY HISTORY (1501-1815)

Ascension Island is located in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean at 7° 57’ south latitude and 14° 22’ west longitude, almost halfway between the continents of South America and Africa. The 35-square-mile landmass lies roughly 500 miles south of the equator, 750 miles north-west of St. Helena, 1,400 miles east of Brazil, 1,000 miles south-west of Liberia, and 2,400 miles north-west of South Africa. The island is an above-water volcanic peak of the longest submarine mountain range in the world, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which runs north to south down the middle of the Atlantic Ocean from Jan Mayen Island to Bouvet Island. First settled in 1815 by the British, Ascension has no indigenous population and houses approximately 1,100 people today.

The Portuguese navigator Juan de Nova initially discovered the island in 1501 during an expedition to India, giving it the name “Ilha de Nossa Señora de Conceiçao” (“The Island of Our Lady of the Conception”), otherwise referred to simply as “Conception Island.” During his voyage home a year later, de Nova discovered the island of St. Helena, which he believed to be much better suited for colonization. The navigator neglected to record his discovery of Ascension, which was subsequently “re-discovered” two years later by the Portuguese naval officer Afonso de Albuquerque. In April 1503, King Manuel I had dispatched Albuquerque and his fleet to provide defense for ongoing Portuguese expeditions in India. Albuquerque spotted the island on Ascension Day—the Christian holiday celebrated on the 40th day after Easter to commemorate Christ’s ascendance to heaven—and, unaware of de Nova’s visit two years prior, renamed it accordingly. In doing so, Albuquerque followed the common practice of the time—as, indeed, had de Nova—of naming a previously unknown land after the feast day on which it was discovered.

(Easter Island, Christmas Island, and St. Helena are other examples of this custom.) As was also customary at the time, the Portuguese released several goats on the island to be used as a future food supply by ships passing through the area. Shortly thereafter, Ascension developed into an oceanic post office of sorts, where messages left by southbound ships would be taken aboard northbound ships for delivery to European ports. Sailors would also frequent the island in search of turtle meat, both for sustenance and to battle scurvy, a common disease at the time resulting from a lack of Vitamin C.[1]

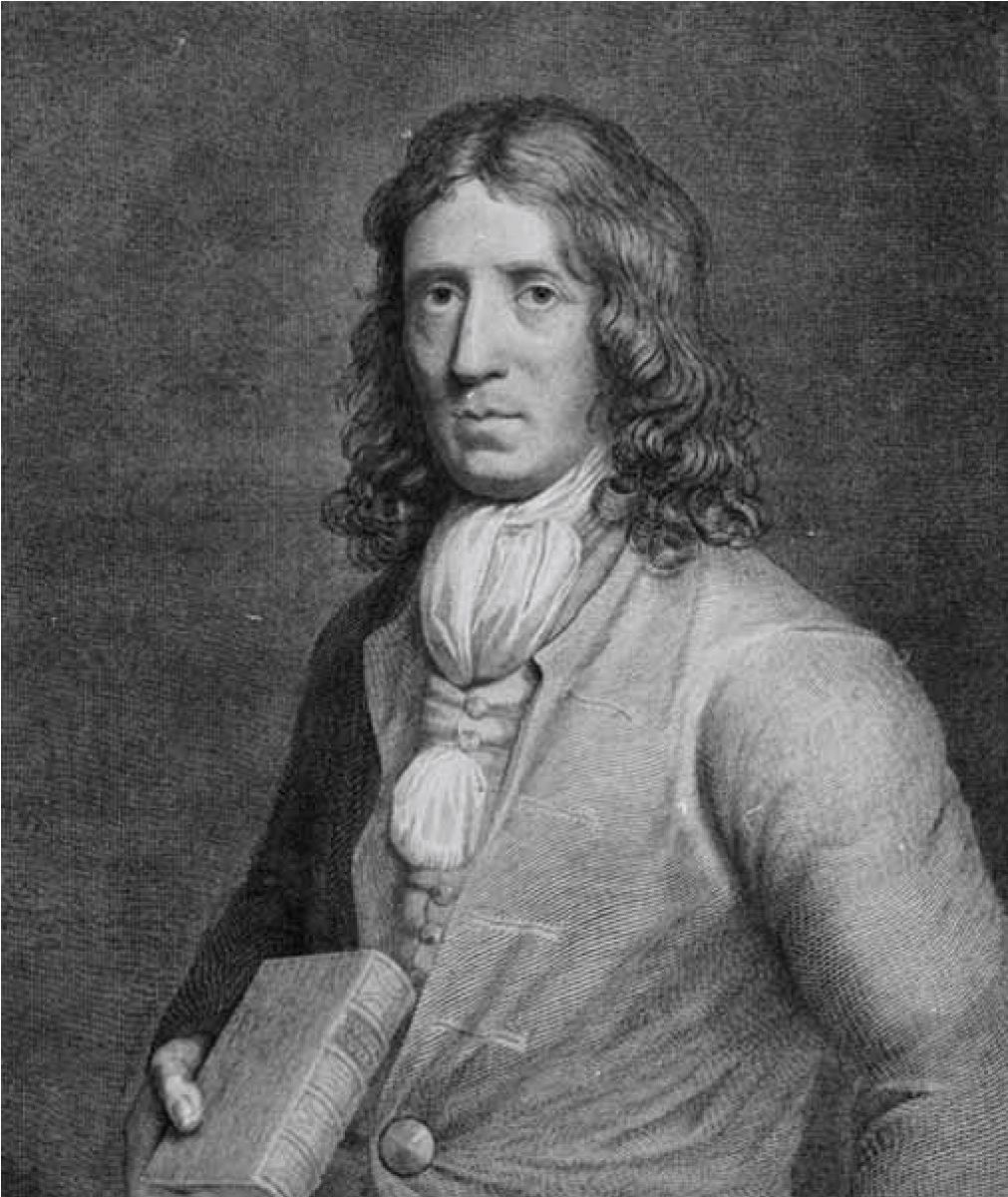

Captain William Dampier

[1] Ascension’s turtles have thrived on the island for generations, predominately due to its isolated location and lack of predators. The massive 400-plus-pound creatures miraculously travel well over a thousand miles from Brazil to Ascension annually to lay their eggs prior to returning home. In the past, turtle meat was a common dish associated with Ascension; however, today the turtles are strictly protected.

For those interested in learning more about contemporary research being conducted on Ascension’s turtles, see Sergio Ghione’s Turtle Island: A Journey to the World’s Most Remote Island.

On 22 February 1701, the English buccaneer William Dampier landed on the island after his ship, the HMS Roebuck, sprung a leak and began to take on water. Dampier was returning from a two-year expedition to New Holland (now Australia) and New Guinea after a breakout of scurvy infected his crew and forced him to turn back prematurely. All of the Roebuck’s men made it safely to shore; however, the vessel ultimately sank the following morning. Dampier and his crew were stranded on the uninhabited island until 3 April, when three Royal Navy ships spotted and rescued the men. The author Daniel Defoe was most certainly influenced by the journeys and writings of Dampier, and Dampier’s wreck on Ascension may have played a role in inspiring the novel Robinson Crusoe.

Perhaps the most legendary story of the island is that of Leendert Hasenbosch, a Dutch castaway confined to Ascension in isolation for five months until his death in 1725. Hasenbosch, an officer in the VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie—the Dutch East India Company), was serving as a bookkeeper aboard the Dutch ship Prattenburg when he was convicted of the crime of sodomy (most likely for engaging in homosexual acts) on 11 April 1725. As punishment, on 5 May he was marooned on Ascension, where he kept a journal of his daily activities until he presumably died of dehydration five months later in mid-October. Hasenbosch’s journal was discovered by the crew of the English East India ship Compton on 19 January 1726 during a return voyage to England. It was subsequently translated from Dutch to English and then published in 1728 under the title An Authentick Relation.

According to the ship’s log, the members of the Compton were unable to discover the body of Hasenbosch, leading to speculation regarding the journal’s authenticity. Some historians have suspected that the translator may have added or modified entries to increase the book’s resale value, and a handful even suggest that Defoe himself may have played a role in the journal’s alteration. The original copy of Hasenbosch’s manuscript has yet to be located, further enhancing the legend of the Dutchman’s short stay on Ascension.[1] In 1775, the English explorer Captain James Cook landed on the island during his second exploratory voyage around the world. Cook, who had recently discovered South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, was searching for the phantom island of St. Matthew in the South Atlantic. He reached Ascension on 28 May in search of turtle meat and, finding nothing else of use on the island, continued onward on 31 May toward the Fernando de Noronha archipelago.

[1] For a detailed analysis of the life and journal of Leendert Hasenbosch, see Alex Ritsema’s A Dutch Castaway on Ascension Island in 1725.

An American ship was wrecked on Ascension in 1799, leaving 15 men stranded until a passing ship, the HMS Endymion, came to their rescue. The men were discovered on 8 September when Sir Thomas Williams, captain of the Endymion, sent boats ashore while passing through the area. It is not certain how long the sailors had been marooned, but Williams managed to board all of them onto his vessel. Although the rescue was a success, Williams recorded in his log the disappearance of one of his own men on the island. After searching for the sailor with no luck, the Endymion set sail and continued on its voyage. A short time after this tragedy, it became customary for passing ships to fire a cannon shot to alert possible castaways of their presence. This practice continued until the island’s formal occupation in 1815.

Cont.