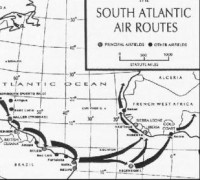

SOUTH ATLANTIC FERRY ROUTE TO AFRICA - FERRY FLIGHTS

7)THE PROJECT X

Project X, as the heavy bomber movement to the

Although a total of eighty four-engine bombers were originally earmarked for the project, something less than that number actually left the

Original orders directed all flights to proceed first to MacDill Field near

The first of these to be ordered to the MacDill Field staging point was made up of fifteen LB-30's* repossessed from the British and manned by crews of the 7th Bombardment Group, a group whose air movement across the Pacific had begun on 6 December. Only six of these planes, under the command of Maj. Austin A. Straubel, actually went through MacDill Field, the others being ultimately diverted to the Pacific route.

Travel orders were issued on 19 December 1941, and within a few days aircraft and crews began to arrive at

Orders were issued on 23 December for the transfer of the sixty-five bombers to the

At

When it became apparent by early January that the delivery of the heavy bombers as far as the

Although the staging of the heavy bombers and crews at Macdill Field came under the control of the Third Air Force, the Ferrying Command was given certain responsibilities in connection with the final processing at

Upon arriving at the field, Reichers found that the LB-30's then being processed were overloaded with all sorts of miscellaneous and excess equipment. He removed an average of over

The planes were to be flown by their own combat crews, and Reichers naturally found many of the young officers and men making up the crews inexperienced, untrained in long-distance flight procedures, and jittery. As with most human beings facing the unknown, some were obviously in fear of the long flight over ocean, jungle, and desert.

It was clear that additional training prior to take-off would be needed if a high accident rate was to be avoided, but the pressure for speed in the movement of urgently needed reinforcements was such that permission to delay the take-off was granted only after an appeal to Washington. In order to carry out its own assigned responsibilities in connection with the training, the Ferrying Command established a control office at MacDill Field in January in charge of Capt. James C. Jensen, a veteran four-engine pilot.

He was assisted by specialists in the various crew positions, that is, pilots, co-pilots, navigators, radio operators and flight engineers, all of whom had had trans-Atlantic flying experience with the B-24 shuttle services to

Instruction was given in navigation, radio, aircraft maintenance, gunnery, and four-engine transition, the latter including, because of the inexperience of the crews, some instruction in night landings and take-offs. Another important aspect of the training program was the briefing of the crews on weather, communications, landing fields, housing, messing, and health conditions along the route.

The briefing of crews for overseas flight would develop into on eof the more fundamental and specialized functions of ATC, but the procedures at this initial stage were rudimentary indeed by comparison with the system that was later set up at aerial ports of embarkation and at overseas stations around the world.

In addition to the information that could be provided out of the personal experience of a few officers, the bomber crews were supplied with maps, charts, and other material on route conditions procured form a variety of sources by the Ferrying Command's intelligence section.

According to officers connected with the project, some 170 maps and charts and approximately 50 books and folders, comprising a mass of undigested, unwieldy information which served to confuse rather than inform, were furnished each crew. Later, as the briefing technique improved, route information was boiled down to the essentials and compressed into well-organized route guides.

Training and briefing the crews and putting the aircraft in shape for the overseas journey were only the first steps in the complex task of moving Project X to the

The majority of the pilots had been trained on single-engine or twin-engine aircraft and because of the inadequate number of planes had at best only fifteen to twenty hours of four-engine flying time before leaving Tampa. In addition to, and partly because of, the inexperience of crews, special problems of morale and discipline developed. Control officers stationed along the route, often themselves new and inexperienced in their tasks, at times felt the lack of that kind of authority which belongs only to a recognized and well-established position.

Equally serious were shortages of gas and oil, primitive refueling and maintenance facilities, and an inadequate weather and communications network. The single problem of providing a sufficient supply of gas and oil at refueling points was staggering in itself.

An estimated 500,000 to

The gasoline had to be shipped and stored in bulk and this required that the shipment of material for tank construction precede that of the gasoline itself. The speed with which the Project X movement was undertaken made it impossible for the Ferrying Command to build up in time a supply of spare parts at intermediate bases, and this one factor was probably more responsible than any other for the numerous delays en route.

Except for the few spares carried by each airplane and some Liberator parts stocked by the RAF at

The small amount of air cargo space available at the time, the priority given to high-ranking military personnel traveling by air, and the almost total lack of transport planes capable of carrying complete engine assemblies mad the movement of supplies by air more than difficult.

Some spares were shipped to West Africa by water and then distributed to points in Africa and

The staging of Project X aircraft and crews at MacDill Field extended over a period of about two months. During that time some fifty-eight heavy bombers of the projected eighty departed for the

In spite of many delays along the way, forty-four of the sixty-six bombers were delivered to the Southwest Pacific area over both routes by late February. Others were diverted to the Tenth Air Force in

Four of the B-17's were lost completely either in crashes or over the Atlantic, another landed in a swamp at Belem, one was forced to return to the United States for repairs, and one was delayed in Africa awaiting repairs even as late as May 1942.Although none of the bombers reached the

It was a good record considering the pioneer nature of the job, the inexperienced and poorly trained crews, and the necessity for building a ferrying route organization through the South Atlantic and across Africa and

After February 1942 all aircraft flight-delivered to the Southwest Pacific were staged at West Coast bases and flown out by way of Hawaii and the chain of island steppingstones extending down to Australia. The number of planes delivered for a time was small, but steady progress was made in the construction or improvement of bases and in the installation of weather and communications facilities in preparation for the heavier movements that would come in the summer and fall.

Ferrying Command personnel made some of the deliveries, and in April two LB-30's were assigned to the route for the return of ferry crews to the

With the cutting of the India-Australia air link and the consequent shift to the Pacific route of heavy bomber ferrying to the Southwest Pacific area, the Ferrying Command control office at MacDill Field was discontinued. Meanwhile, in January the command had been assigned jurisdiction over Morrison Field near

A subheadquarters of the command, known as the South Atlantic Sector, was established at the field and an experienced Ferrying Command officer, Col. Paul E. Burrows was appointed commanding officer of both the sector and the air base. In order to concentrate all ferrying activities at the one base, the 3131th materiel Squadron and certain key officers were transferred from

At Morrison Field the 313th Squadron performed 1st and 2d echelon maintenance, while heavy maintenance work of 3d and 4th echelon became the responsibility of the subdepot established at the field by the Air Service Command in late February. Aircraft maintenance was the most important aspect of the staging job at this time, for the success of a flight depended largely on the mechanical condition of the airplane on take-off. And it would be some time before maintenance facilities at bases along the foregoing routes compared favorably with those at ports of embarkation within the

When lend-lease shipments were temporarily suspended immediately following Pearl Harbor, doubt existed in the minds of some as to whether the

Would the needs of American armed forces preclude the further shipment of aircraft and other supplies to

This decision, to distribute arms in accordance with strategic needs, had formed the basis for the diversion of heavy bombers originally consigned to the British in the Middle East to American forces in the Southwest Pacific; it also assured continued support in the form of twin-engine bombers, fighters, and transport aircraft to British imperial forces in Africa and India, as well as to the Russians and Chinese.

The

Throughout the fall and winter the organization had been busy recruiting and training flight and ground personnel in preparation for a greatly enlarged operation as soon as the aircraft began coming from the factories in quantity. As in the case of pre-Pearl Harbor deliveries, most of the aircraft ferried out by Pan American crews during the winter of 1941-42 were two-engine transports destined for the British or for Pan American Airways-Africa. An unusual assignment had bene undertaken in December and January when four PBY flying boats, carrying loads of .50-cal. machine-gun ammunition, were ferried by way of the South Atlantic to the Dutch in the

Deliveries began to pick up in March with the arrival at the

For several months nearly all of the B-25's were flown from

Between March and the end of 1942, a total of 102 B-25's were flight-delivered to the Russians over the southeastern route. Though most of these were ferried by civilian crews of Pan American Air Ferries, some were flown out by military crews. Lend-Lease A-20's for the Russians began to arrive in the Persian Gulf area by water transport as early as January 1942, but not until the following October were the first deliveries of these Douglass light attack bombers completed by air. [Seventy-one were delivered in October, sixty in November, and seven in December.

Following the collapse of the Allied effort in java, urgent demands for reinforcements came from

Fifty P-40E's had been allocated to the AVG in January, and during the same month thirty-three A-29 Hudsons had been earmarked under lend-lease for the Chinese. From beginning to end, the A-29 movement was beset with trouble, vexatious delays, and untimely accidents. The aircraft were in poor mechanical condition when taken over by the ferrying crews and were overloaded with medical and other supplies for

These factors, together with the relative inexperience of many of the crews, were responsible for an unusually high accident rate. Three planes were lost in crashes before the project left the

Because of Rommel's threat to Egypt that summer, the A-29's were held up in the Middle East for a time and might have been assigned permanently to General Brereton's forces there had not the persistent demands of the Chinese brought about their release.

Of the thirty-three planes originally allocated, twenty-two were turned over to the Chinese Air Force during the summer and fall. While it was impracticable to ferry fighter aircraft over the whole of the southeastern route, they were moved in large numbers under their own power over the land route from West African bases to the Middle East,

Within a few months after Pearl Harbor, the

Arrangements were made for use of the British assembly plant at Takoradi, where the planes were prepared for the overland movement. Losses were suffered en route, but by June most of the original fifty had crossed into

Comprising one element of a general reinforcement of the Tenth Air Force, the P-40's were flown to

Two of the eight-plane convoys into which the P-40's were organized became lost over the African desert because of navigational errors. As a result, nine of the fighters cracked up. Other difficulties were encountered and numerous delays experienced; perhaps no more than fifty-eight of the planes eventually reached

Karachi had become, generally speaking, the terminal point for Ferrying Command operations to the East, and until December 1942 the responsibility for development of the trans-India service into

Twin-engine transport planes were the only aircraft to be ferried to British forces in

They were not in sufficient number to be of much help in stopping Rommel at El Alamein, but during the late summer and fall an increasing flow of twin-engine bombers departed from

Between June and the end of the year, 398 Lockheed and Martin medium bombers--including 120 B-34's, 153 A-28's, 45 B-26's, and 80 A-30's--were ferried to British forces in Africa by crews of Pan American Air Ferries or by American and British military crews. At the same time, the forces gathering under the leadership of General Brereton during the summer and fall, first as the United States Middle East Air Force and later as the Ninth Air Force, reached their battle stations in large part by use of the

The

That help would be limited chiefly to assistance in the air, and it was made possible by the progress already achieved in the development of strategic air services by the southeastern route. American air combat in the

When the detachment reached the Middle East it was held, temporarily it was believed at the time, for the purpose of carrying out a single mission against the Ploesti oil fields of Rumania on 12 June; but following Rommel's success in breaking through the British defenses at Cyrenaica, aircraft and crews were assigned permanently to General Brereton's newly created Middle East Air Force and were absorbed eventually by the Ninth Air Force.

In helping to prepare HALPRO for overseas movement by air and in controlling the flight along the way, the Ferrying Command gave clear indication of having learned much about its job in the months that had passed since Project X moved over the southeastern route to the

Sufficient time was taken at the assembly point at

The detachment was organized into three flight echelons of 7-8-8 aircraft, with flights spaced about two days apart in order not to overcrowd facilities along the route. A few of the aircraft were delayed briefly but caught up with their flights, and all three echelons arrived in the

Consolidated B-24 The most successful Bomber produced for US Army Air Force. 19,256 aircrafts were produced at the unitary cost of US$ 297.627. Source Wikipedia

Boeing B-17. The second bomber in production. 12,731 aircraft produced at the unitary cost of US$ 238,329. Source Wikipedia