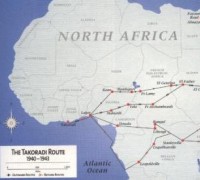

THE TAKORADI ROUTE - THE JOURNEY TO EGYPT C.B.I.

2)A B-25 ACROSS THE ROUTE

By Bob Dethlefsen

The pre-flight briefing we had been given pertained primarily to the weather conditions that we were likely to encounter. A great deal of stress was put on the fact that there was a stationery front that lies across our path to

It should be pointed out however, that these had been flown by experienced Ferry pilots and navigators who had been around a bit longer than we had. We were to be the very first B-25s to be flown by combat crews through South America and across the

The rain rained, the hail hailed and the lightening flashed. The instrument panel shook so badly we could not read the gauges, but with both of us hanging on to the steering wheel we managed to stay reasonably upright and, just as the man said, we broke out in the clear on the other side. If there had ever been any doubt about how well a B-25 was put together that doubt had been dispelled. Even heavily overloaded as we were, I don't think we popped a single rivet.

And Krazy Glue had yet to be invented! Of course we had zigged and zagged so many times, that the Navigator didn't have the vaguest notion as to where we now were. In his defense it must be said that he had only recently completed navigation training, and without following the headings he gave us, we were asking him to guide us half way around the world.

At this point we began to understand why we had left

That night, after rest, fuel and aircraft servicing, we again headed south for

The flight across the Atlantic was to be non-stop to Roberts Field in

Shortly before midnight May 6, 1942 B-25 41-12513 took off from

While we excitedly pondered who, what and why this was happening so far south in the

Then, shortly before dawn, the bubble burst. The navigator owned up to the fact that he didn't know where we were and hadn't known for some time. Well, no matter, so what else is new! But this time there was something new---with only a very large ocean below us, the map didn't do us much good. But, we still had a good bit of fuel and

As I claimed to know essentially nothing about navigation, I did the driving while they argued about which direction to try next. As we zigged and zagged once again, it soon became quite clear to me that we were in serious trouble and stood a good chance of ending up in the drink. Ending up in the drink, in the

It stood to reason that constantly changing course was not a good thing to be doing. Since we did not know whether we were north, south, east or west of where we would like to be, it seemed our best chance was to take a 45 degree course and hope that land showed up before we hit the water. The fuel remaining soon became seriously low and we began to think about, and prepare for, ditching. No matter how indestructible the B-25 seemed to be, it's designers had never taken into consideration how well it would float.

As far as the eye could see, low clouds stretched in every direction so it became necessary to descend to just above the waves if we were to see any great distance ahead. But then, there it was, without a doubt, land showing up through the clouds ahead. But we still had a long way to go and the fuel gauges were all essentially reading ZERO. It was hard for me to believe but the suggestion was even considered that we now actually try to find Roberts Field. That idea faded quickly when it was decided that a controlled landing on the beach was far superior to running out of fuel and perhaps going down in the jungle.

It appeared that we were approaching the land at a rather shallow angle so with a bit of a turn we made a landfall much more quickly, and soon were able to line up with straight stretch of beach. The plan was to belly in with the gear up but, as we got a better look at our "airstrip", I could see that there was a grassy border which offered the good possibility of a satisfactory gear down landing. With no time for discussion, down went the gear, locked in place a split second before touchdown. It was a good landing-not perfect-too long and too fast.

The trees ahead came up too soon and braking was necessary. This brought the nose down while still moving at a pretty good speed, causing the nose wheel to dig in and the gear to collapse. The glass bombardier's station had been crunched to about half size and both propellers were curled back. But we were safely on the ground with no physical injuries. We had been in the air almost exactly 12 hours

One Squadron of B-25 flying across the desert on the legendary Takoradi Route still far away from their final destination Egypt.