- COMMANDER SOUTH ATLANTIC

9)WINNING OVER PRES. VARGAS

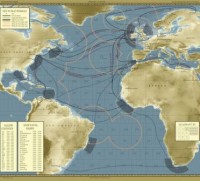

The War swung into the early months of 1942. In some ways this was the most trying period of all for Task Force Three, which soon was changed in name and became Task Force Twenty Three of the Atlantic Fleet. A little later Rear Admiral Ingram received the promotion which made him Vice Admiral. This raise in rank meant much in facilitating negotiations with Brazilians. Rank means everything in their country, where the little Rear Admiral was fairly common, despite the smallness of their Navy at that time.

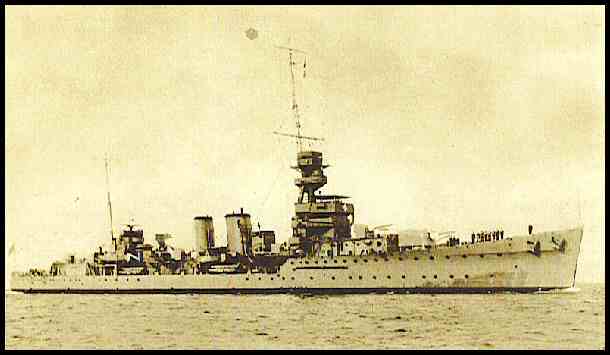

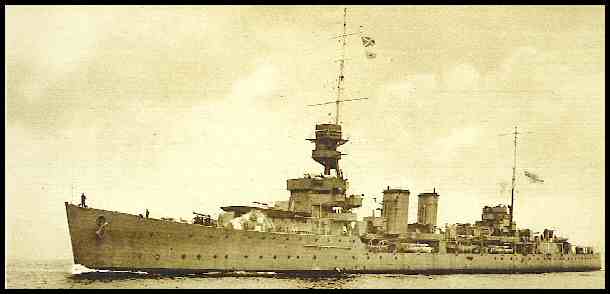

Vice Admiral is rarer, and Brazilian Officials naturally felt pleasure at having an Officer of such rank named to deal with them. The area assigned the Admiral for coverage was the South Atlantic below 10º N, and west of the 20º Meridian At this time the patrol arrangement with the British in West Africa had been worked out to a limited degree only. However, two of H.M.S., the Diomede and the Despatch, were presently assigned to work with the Task Force, and the Diomede reported for Duty on January 31.

The presence of British ships aroused again the unpleasant issue of Brazil's hostility to England. Unofficially, at this time, the Admiral was told not to bring the Royal Navy vessels into Brazilian ports in the expectation that they would receive the privileges enjoyed by the U.S. Ships of Task Force Twenty Three. Although the British authorities were considerably worried over the matter, the Admiral decided that it would be unwise to press the issue just then.

Partly to remove a possible subject of contention, he sent the Diomede to do patrol work off the Uruguayan coast. She would use the port of Montevideo, where anti British feeling did not run so strongly. Since the Brazilian attitude toward the United States was better, if anything, then before Pearl Harbor, it seemed a mistake to jeopardize it.

The arrival of the seaplane detachment and tenders at Natal, and the extensive air and seaplane base construction that by this time was going on at Bahia, Recife, Maceio, and Natal, indicated the need of a personal inspection of these places by the Force Commander. For this purpose the Admiral shifted his flag temporarily to the Destroyer Winslow from the Memphis, while the latter with her Task Group went on the regular São Roque – Cape Verde area patrol.

During the inspection of the ports, the Pan-American Conference, designed to promote hemisphere solidarity was in session at Rio. On this trip the Admiral noted that the Brazilian Officials were keenly aware of what was going on in their Capital, and seemed entirely disposed to support Brazil’s national policy. This did not apply to the general public, which continued as apathetic as ever.

So great, in fact, was the apparent popular indifference to the world situation that it required a direct German threat to stir things up. A Nazi broadcast, promising bombing retaliation on Northeaster Brazil for the aid and shelter given ships of the U.S.Navy, produced the only general sign of life and interest hitherto seen.

A tour of Natal, Maceio, and Bahia involved contacts with the Interventors and Officials of three additional Brazilian States – Rio Grande do Norte, Alagoas, and Bahia. For some time the Admiral had been cultivating these men, civilians and military alike, and at the conclusion of his tour he could truthfully declare himself satisfied with their cooperation. Especially important here were Rear Admiral Dodsworth Martins and Brigadeiro Eduardo Gomes.

Admiral Dodsworh Martins commanded all Naval units operating between Rio and the Amazon River. His Force consisted of an old Cruiser (the Bahia) which served as his flagship, plus several armed patrol boats and coastal minelayers. Admiral Ingram arranged with him for the Brazilians to take over and organize the inshore patrol.

Radio men were assigned from Task Force Twenty Three to teach American procedure to the Brazilians and to organize communications. The Patoka built a depth charge rack on the stern of the Bahia, and one hundred 300 lb. depth charges were turned over to the Brazilian Admiral. VP-52, the seaplane detachment, reported results of patrols to him and the U.S. Naval Observer also cooperated.

Brazil, as it must be again strongly emphasized, was still a neutral in the war. But she had already taken one compromising step in affording facilities to Americans, and therefore must be as alert as her limited Naval and Aviation facilities would permit. For this reason Admiral Dodsworth already acted partly as an ally.

Brigadeiro Gomes, the FAB (Força Aerea Brasileira) Commander for the Second Air Zone, was in charge of the most strategic Brazilian territory; that lying on the “hump”. Gomes, in some ways was a difficult character to deal with. He was, and is, a national hero in Brazil, a “strongman” with prestige far in excess of his rank.

Some opposition was frequently to be encountered from Gomes. Yet, as an extremely patriotic Brazilian, he appreciated the need for strengthening the “hump” against a very possible Axis aggression. It was satisfying to note that the Brazilians had stationed their finest Anti-Aircraft batteries at Natal.

These consisted of eight A.A. guns, recently made in Germany, with excellent Sperry lights and control. Through Gomes influence, the Admiral later obtained the use of the abandoned German Condor seaplane base at Natal for the personnel of VP-52 to use as living quarters. Gomes, moreover, took the lead in urging that a squadron of American pursuit planes and bombers be assigned to Natal; an opinion in which the Admiral heartily concurred.

At Natal, on the inspection trip, several pertinent observations were made. Pan Am Airways had a seaplane base there, which was just what the Force needed and certainly far superior to anything else noted in the Caribbean or Brazil. Acquisition of the Condor properties nearby would let the seaplane detachment up well. The city of Natal itself was a poor liberty port, offering little in the way of amusements or quarters. It must be arranged therefore for the men to have their own living accommodations and recreational facilities.

The Admiral gave words of commendation for the VP-52 Commander and the American Consul at Natal, but was not satisfied with the Naval Observer, whose detachment he recommended. There was the additional suggestion that he be replaced by Lieutenant Commander C. B. Gary, Naval Observer at Maceio, who was doing well there, but who had not enough work to employ him fully. The substitution was made, as recommended, on March 23. Maceio, it was found, would offer nothing to Task Force Twenty Three as a port.

The shallow harbor prevented larger ships from docking. Supplies were scarce, protection was lacking, and the town was uninviting to liberty parties. The one potentially useful thing was the seaplane base, built on filled-in ground on a lagoon. Lacking were such important items as security, drinking water, living quarters for personnel, communications and storehouses. Yet the admiral considered the location so good for seaplanes that he recommended the addition of the facilities needed.

Bahia had the same advantages and disadvantages that it had presented the previous year. An excellent harbor, it was nevertheless inconvenient for ships, being too far south of the vital area. The fuel shortage persisted, as did also the inadequate provision supply. Once again, in appraising the situation there, the Admiral made favorable comments about Brazilian Officials. He expressed the warmest approval of the U.S. Naval Observer, Lieutenant Saben. Mr. Castleman, the American Consul at Bahia, also received praise for his valuable cooperation.

Regarding the overall picture of the Naval situation in Brazil, problems continued to be numerous. The fuel situation, for example, had always been unsatisfactory to the country’s own officials, so not much reliance could be placed on local supplies. U.S. Navy Tankers, especially the Patoka, had to make frequent runs between Trinidad and Brazilian ports to carry oil. The Patoka, being a Tender and Supply ship as well, was too valuable to be away for any extended periods. The Admiral, therefore, stressed the need for a regular Tanker.

He felt that as matters stood at the time, one trip every three months should be enough to replenish reserves. Another difficulty concerned the limited quantity of aviation gas at Natal, where the Pan-American supply was inadequate and where the storage place available sufficed for only about 40,000 gallons. At this time, reported the Admiral, negotiations were under way at Natal to increase the gas reserve to 100,000 gallons.

From February through May 1942, five Task Groups of Task Force Twenty Three operating in the assigned area, extending their surveys as far south as the Falkland Islands. Frequent necessity for escort duty and anti-submarine operations in the Caribbean disrupted the cruising planes again and again. During this time an Army expedition came from the United States to set up an Air Base on Ascension Island, colloquially known as the “Rock”. The men and material arrived in the U.S. Army Transports Coamo and Luckenbach.

They were picked up by ships of Task Force Twenty Three in 15º North Latitude, and convoyed first to Recife. On March 27th, the Coamo left there for Ascension, followed the next day by the Luckenbach. The Transports were escorted all or part of the way by the Memphis, Winslow, Jouett, Cincinnati, Sommers and Greene. During the delicate landing operations, when the danger of surprise enemy action was acutest, a Light Cruiser and two Destroyers kept constantly underway and on guard. No enemy appeared, but had one done so the ships would have been extremely vulnerable.

Unloading the troops and material at Ascension proved difficulty, due to trying weather conditions and inadequate shore handling facilities. The officers lacked experience in operating under these conditions, the ships had been poorly loaded in the first place, and the C.I.O. members of the merchant crews proved a constant source of trouble. Probably the unloading could not have been accomplished without the initiative and resourcefulness of Naval personnel.

The Army officers and men did their best to assist, but Navy boats, working parties, leading men and winch men played the important part. The C.I.O. crews followed organized labor procedure at all times refused duty out of hours and jeered at Naval personnel for exerting themselves.

The latter naturally resented this attitude, and one or two occasions a physical clash was narrowly prevented. Thus began the base of Ascension, which when the inside history of the war is better known, will come in for its fair share of recognition. Few contacts with enemy submarines were made during this period, yet the Force did record its first kills. U-Boats began to strike, first in the Caribbean and later along the Brazilian coast. They came to Brazil at a very inopportune moment. Two days after this, the Jouett, while on a sweep off the Dutch Guyana coast, made an attack on a surfaced submarine at night.

When the fear of German submarines caused the Brazilian Government to decide to freeze its shipping, the Admiral determined to take the matter up with the head of the firm, namely President Vargas. He left Recife in the Memphis on April 4, and the Cruiser first made a nine day voyage to Montevideo. There conferences were held with the American Minister, the U.S. Naval Attaché, and various Uruguayan officials. All went extremely well. An agreement resulted whereby the U.S. Navy could utilize the services of a British Radio Receiving Station at Montevideo, including participation in the special arrangements maintained between that station and the Falkland Islands.

One Task Group was pinned at Ascension, a second and third were too far distant to be of any immediate help, while the fourth was compelled to relieve the Ascension Group, regardless of the submarine situation. This at first left but one Group, supplemented by shore based planes, to deal with the subs. There was presently organized an anti-submarine striking force of two BL,s to work with the combined U.S. - Brazilian air arms. On May 7, the Winslow was escorting the Patoka from Recife to Port of Spain.

At Latitude 02º 25’ N, Longitude 45º - 55” W, while on base course 304º, this Destroyer located a submarine at 320º, relative bearing. Depth charges were dropped at ten second intervals. A snub nosed object broke the surface at an angle of 70º, rising to a height of 8 or 12 feet, and then dropped back, obscured when the whirl of the next depth charge reached the surface.

Personnel on the bridge, secondary conn and searchlight platform of the Winslow, were unanimous in describing the object as the bow of a submarine exposed topside. This was reasonably taken for a kill, especially as no further contact could be made.

Evidently the underwater craft was destroyed. The total of enemy contacts made was not numerous. Even more important than the sinking of subs, was the need to keep the convoys moving, and the supplies reaching their destinations. The presence of the Force in the South Atlantic, by discouraging enemy submarine action, kept the traffic in motion. An illustration of this is furnished by the fact the Atlantic Coast South American Countries decided to “freeze” their shipping when the first submarine scare broke. That they soon reconsidered and released the ships was due to the presence of Task Force Twenty Three.

The Government of Uruguay was pleased at the visit, especially as the rank of Vice Admiral now belonged to the Commander Task Force Twenty Three. It was plain that Uruguay would support the United States to the extent of allowing the use of her ports and airfields. Excellent provisions would be available in that beef and wheat raising country. Uruguay, unlike her neighbor Argentina, showed no tending toward Axis dealings.

President Vargas was at this time at Poços de Caldas, a resort spot in the southwestern part of Minas Gerais. On learning that the Admiral was in Rio, he at once asked to see him, and requested that he come with no accompanying him save Captain Brady. With Commander F. J. Laningan, later Comandant of the Base at Rio, piloting the plane, the small party flew to Poços de Caldas. The visit proved to be the diplomatic highlight of Admiral Ingram’s experience in Brazil. Captain Brady, whose Portuguese was fluent, acted as interpreter.

The Admiral began by telling the President that he came to him the hard way, through the provinces. The point of this remark was that for almost a year much attention had been paid to cultivating good will with the Brazilian civil and military authorities of the Northeast. It could now be observed what excellent dividends this policy had paid, since President Vargas, fully informed of the reputation the Admiral enjoyed among his subordinates, proved cordial. No ice existed to be broken.The President received a detailed account of the state of affairs.

Included were such items as the effect upon Brazil of the submarine menace, the Admiral’s proposed measures to protect neutral shipping, and the needs of the American Force. As Vargas learned the fact of the case, he asked many questions, all intelligent. Toward the close of the interview, the President expressed gratitude for the clearest synopsis of the situation he had ever been given. He then asked a final question, would Admiral Ingram assume responsibility for the protection of Brazilian shipping if it were “unfrozen”?

The Admiral’s answer was yes, with one reservation; he would not guarantee to be entirely successful. The risks were mutual and must be shared by all. Privately the Admiral realized that the United States would have to bear the blame for anything that was wrong. He therefore felt it best to assume full responsibility for the ships of Brazil. The sooner they were at sea again the better.

The qualified answer seemed to satisfy the President, who proclaimed the American Admiral his Sea Lord and asked him to serve as his Naval Advisor. At the time this unofficial pact was made, the Force at the Admiral’s disposal for conducting the fight against submarines in the South Atlantic consisted of the following. Cruiser Division Two still included in the Memphis, Milwaukee, Omaha, and Cincinati, to which the Marblehead had subsequently been added.

From Montevideo Memphis sailed to Rio, arriving on April 22. Here the Admiral met the Ambassador Jefferson Caffery, whom he had not known before, and Captain Edward Brady, the Assistant Naval Attaché, whom he knew well. Admiral and Ambassador got along famously, and the former, guided by the two American officials, made the round of courtesy calls on Brazilian officials. The rather overpowering personality of Osvaldo Aranha, Brazil’s Foreign Minister, was impressive, and the Admiral also reacted favorably to General Goes Monteiro. He was particularly struck with Admiral Mello, the Naval Chief of Staff, who seemed an excellent officer.

In addition there was Destroyer Squadron Nine, made up of the Davis, Moffet, Somers, McDougal, Jouett, Winslow and Greene. The other ships of the Task Force Twenty Three were the Patoka, Auxiliary Oiler, the Thrush, Auxiliary Seaplane Tender, and the Nitro, Auxiliary Ammunition Ship. The planes of VP-83 had relieved those of VP-52 in the latter part of April at Natal. Finally, there was the H.M.S. Diomede, still patrolling off Montevideo.

H.M.S. Diomede and H.M.S. Despatch. Both Royal Navy ships went far south in the Atlantic on request by Admiral Ingram for whom that vast area should have a more efficient patrol system against the Axis submarine menace.

HyperWar - Commander South Atlantic Force. U.S. Naval Administration in WW II