- COMMANDER SOUTH ATLANTIC

6)THE ODENWALD

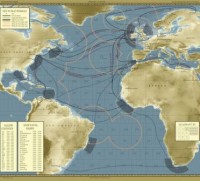

Early in November 1941 the monotony of South Atlantic patrol work was relieved by the taking of a German ship. On the 6th of the month, Task group 3.6 consisting of the Omaha and Sommers, was traveling on course 288º enroute to Recife. The ships had been on an unsuccessful search for a raider that had fired on the British SS Olwen. Daybreak came at 0430 that morning.

At 0506 the Group sighted a darkened vessel, bearing 251º (T). Captain T. E. chandler of the Omaha, Task Group Commander ordered the course changed to intercept and investigate the stranger. Standard speed at this time was 14 knots, which in a few minutes was increased to 18, and a little later to 25. At his time the appropriate position was Lat 00º 14’N, Long 27º 44’ W. The strange ship received directions by searchlight to make her international call, but gave no answer.

Upon closing her, it could be seen that she flew the United States flag, with American flags painted on both her sides, just below the bridge. From her signal halyard flew “K I G P”, the International Call of the US Merchantman Willmoto of Philadelphia. On the stern was painted Willmoto-Philadelphia. At this time, a man on board the Sommers noted that stranger had the same hull design as a German Navy Survey Ship which he had seen early at Miami. Captain Chandler, through the megaphone, called, “Why don’t you answer signals”? This question brought no reply and was repeated again without result. Then questions were asked and answered as follows:

Q. Where are you from?

A. Capetown

Q. Where are you bound?

A. New Orleans.

Q. Why don’t you answer signals?

A. No answer.

Q. What is your cargo?

A. General cargo.

While this went on, the Omaha cruised around the suspicious vessel. Observers had already noticed that several of her characteristics did not coincide with those of the Willmoto, as given in “Merchant Ships of the World 1940”. Also apparent was the fact that some of the men aboard her, were decidedly un-American in appearance. It was decided to send a boarding party from the Omaha, and a crew in charge of Lieutenant G. K. Carmichael, USN, left the ship immediately to search the stranger.

As soon as the mystery ship’s personnel saw the boat lowered into the water, they hoisted “Fox-Mike”, meaning “ I am sinking send boat for passengers and crew”. At the same time they began abandoning ship, and the Sommers signaled that they had been seen to throw overboard a large package.

Here was positive proof that something was wrong. The boarding party reached the ship about 0645, and at that time two explosions were heard in her, apparently from the after part. As Lieutenant Carmichael came along the starboard side, two boats were already in the water, and sea ladders were rigged. The personnel had begun to get into the boats.

However, Lt. Carmichael ordered them both back to deck, and from the first officer learned that this was a German ship. At 0648 the boarding officer sent this message back to the Omaha “This is a German ship”. Their crew is trying to leave the ship. They say it is sinking aft. I tried to get down there but smoke prevented. I am bringing the crew back aboard”.

Lt. Carmichael had told the German officers they had better not let the ship sink. That if they tried any more sabotage, he would have his armed guard fire on them. An attempt to locate the German Captain, whose name turned out to be Loers, revealed that he had already left in another boat. He soon returned, but at first would give no information, other than to state that his ship was sinking.

Meanwhile, aboard the Omaha captain Chandler having established the German nationality of the vessel, sent a secret dispatch to the chief of naval operations. He catapulted both the ship’s planes, ordering them to maintain a vigilant watch for submarines and surface craft, and direct the Sommers to keep a careful patrol around the Omaha.

Instructions to the boarding officer were to do all he could to keep the German ship from sinking, with due regard for the American seamen aboard. Lt. Carmichael, having made a quick investigation soon signaled back that the captured ship was the German Odenwald. All the German officers and crew, with the exception of the Captain and one other officer, were brought aboard the American Cruise.

The total number of persons taken into custody was 45. The other Odenwald radio officer stated to a member of the Omaha’s boarding party that just prior to abandoning ship, he had sent a dispatch to the German Government, saying that they were being followed and overtaken by warships and that they were scuttling. Apparently he had not included the nationality of the pursuing ships in his report.

All radio equipment aboard the Odenwald was found destroyed. Efforts to save the ship were made at once and ultimately proved successful. The flooded areas were isolated and all available drain pumps put to work. The German chief engineer was sent back from the Omaha and twice taken into the engine room, in the hope that he would help to get his ship going, but he would give no assistance. Each of the other German engineers was conducted to the engine room without the knowledge of the rest, but with one exception they refused any help in starting the engines.

The exception was Wilhelm Seidl, Second engineer, who at the point of a gun explained a point or two. Seidl remained aboard the Odenwald for the balance of the trip, and had quarters separated from the rest of the Germans. Knowledge on their part that he had cooperated slightly with the Americans made them consider him a traitor. Threats against his life were heard, and for Seidl’s own safety he was kept in isolation.

The truth was that his assistance had been trifling, but the Germans could not be induced to believe this. It was a party of men from the Omaha’s Engineering Division who finally got the Odenwald started. At 17 40, one of the engines was in operation. At 18 10, Task group 3.6 plus the Odenwald, got under way on base course 283 (T). The Sommers patrolled ahead, maintaining listening watch, then came the captured ship, with the Omaha following astern.

The original intention of the Task group Commander had been to proceed toward Saint Paul Rocks, and, should the Odenwald be unable to proceed to port, to beach her there. But at 19 55 the boarding officer signaled that the Odenwald was going ahead on both engines, that flooding was under control, and that the list was only 2-1/2º

This called for new planning. There now seemed no point in going to Saint Paul Rocks. The Task group had originally been making for Recife, having nearly completed a patrol of 3,023 engine miles, much of it at high speed. The search for the Olwen’s assailant had depleted oil, and the time of interception of Odenwald, the group was within 657 miles of Recife, its commanders deeming that they had scarcely enough fuel to make any other port.

But it seemed highly desirable not to involve Brazil in the affair, and such an involvement could not be avoided should a captured ship be brought to Recife.

Some refiguring showed that careful management, with no breakdowns or bad weather, could probably get the Group into Port of Spain, Trinidad; a much more desirable port under existing circumstances. So it was decided to take the risk. With all economies being practiced, including the rigging of a sail on board the Sommers, which is believed to have cut fuel consumption by 5 gallons an hour, Task Group 3.6 got to Trinidad with the captured ship.

The Odenwald proved to have a cargo on board consisting chiefly of raw rubber (3857 metric tons). She carried smaller quantities of oats, peanuts, truck tires, brass, tannic acid, and wool, and still lesser amounts of oatmeal, copper, dried fruits, wax, roots, hair, fish oil, nuts and tea. From conversations with the German officers, the Americans learned that the Odenwald had been in Japan for about two years, and that during this time constant efforts had been made to take her out.

She belonged to the Hamburg-America Line, but the crew was largely a pick up affair. Even Captain Loers was not a Hamburg-America employee, having been in command of the ship only since August 18, when it had been turned over to him due to the illness of his predecessor. Several members of the crew had been in San Francisco, California, as late as June 1941. There they had undergone temporary internment by the immigration authorities, who finally allowed them to sail for Japan in the Nitta Maru, on June 21. They had obtained her cargo from various and sundry sources.

Most of the Germans did not seem to might being prisoners. However, they were of the opinion that they had almost reached safe waters when captured. They had been told if they got through the day of November 6, they would run little further risk of interception. The crew had expected to be home in Germany to celebrate Christmas. Officers and men alike were sure Germany would win the war. They did not take Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis very seriously, and made fun of both the Italian and Japanese.

From Trinidad, where the ships were refueled, Task Group 3.6 proceeded with the Odenwald to San Juan, P.R. , where on November 19,custody of the German ship was transferred to a representative of the Commandant Tenth Naval District. There had been no properly qualified photographer with the Task group, so no pictures of the Odenwald could be taken until her arrival in San Juan.

The apprehension and seizure of this ship was considered a very satisfactory operation. The Task Group Commander commended the conduct of all personnel under his command. Though it had involved no fighting, the incident furnished good training experience to all hands, particularly those of boarding and salvaging party, under conditions as closely as possible approaching those of actual war.

An interlude of only one month elapsed between this episode and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. For the intervening weeks there is not much to record from the operational side. On November 20, the Chief of naval Operations reported a raider off Saint Paul Rocks. The Cincinnati accordingly swept the area, but without success. A little later the Jouett made a submarine contact in Latitude 02º 00'N, Longitude 29º 15’W.

The destroyer dropped 8 depth charges, with no apparent effect. The Cincinnati, while south of Azores, had a torpedo fired at her, which was scored as a near miss. The Destroyer Leader accompanying the Cincinnati at the time made an effort to locate the submarine, but could not do so. This was the extent of activity up to December 7.

HyperWar - Commander South Atlantic Force. U.S. Naval Administration in WW II