- COMMANDER SOUTH ATLANTIC

2)THE NATURE OF THE PROBLEM

This is the story of the fleet campaign that won and held control of the South Atlantic during the most critical period of the war. At a time when the communications with fighting zones all over the globe were precarious, when everything depended on convoys that must go through on schedule, the South Atlantic was as vital an area as any that existed. For a long period the Mediterranean was closed, or at least could be used only with the greatest risk.

Yet Egypt had to be supplied at all costs, for an Axis Break-through in the Near East would have been disastrous. Russia needed American and British supplies, and a large percentage of these must be sent around the Cape of the Good Hope. With the Japs threatening both India and Australia, much of the aid that reached those countries had to go via the South Atlantic.

Needless to say, the Axis did all in its power to disrupt the schedule, and its method was the employment of submarines. The American answer was the Fourth Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Jonas Howard Ingram, and the answer proved satisfactory. Long before Pearl Harbor, military and diplomatic authorities in the United States knew that the South Atlantic in general, and Brazil in particular, would ultimately be of great importance.

Although the problem was little known or understood by the public at home, a glance at the map was enough to reveal its basic nature. Essentially there was nothing complicated about it, the thing was perfectly clear. The shortest distance between the Eastern and Western Hemispheres is the mileage separating Dakar , in French West Africa, from Natal on the shoulder of Brazil.

In the Atlantic, a little west of Dakar, lie the Cape Verde Islands. They are owned by Portugal, a weak country ruled by dictator Oliveira Salazar, who in the critical period of the war was considered highly undependable. Following the fall of France and the establishment of the Vichy government (June 1940), the importance of Dakar became more evident than ever.

The important factor on the American side of the South Atlantic was Brazil, and there was no assurance as to where her sympathies lay. A huge, undeveloped country, large than the continental United States and containing a mixed population of between forty and fifty millions, brazil spoke the Portuguese language, admired fallen France, generally disliked the British, and had a few definite ideas about the United States.

Certainly it had been the Axis, not the Democracies, that in the years immediately before the war had done most of the propagandizing in Brazil. There were (and are) about 830,000 first or second generation Germans in the country, around 2,000,000 Italians, and some 200,000 Japanese.

Of the Germans, many were known to be active agents of the Fatherland. They were organized into Bunds and Nazi youth Movements, employing all the familiar devices to win power and influence. They owned and controlled newspapers, sponsored radio programs, and tried to arouse Brazilian sentiment against the Jews. The Italians were less political active, and after emigrating were more disposed to transfer their loyalty to Brazil, but fascist influence was widespread among them.

Vichy lacked the physical force to resist the Germans should the latter choose to step into French Africa; moreover it was not certain that Vichy wanted to keep them out. Added to Dakar, there were the lesser problems furnished by other French colonies, such as Guiana, and Martinique and Guadaloupe in the West Indies.

The Japanese suffered the handicap of being completely alien to the Brazilian population. They could not expect to gain the influence that the European Axis members could, but they nevertheless did much plotting and secret meeting, with a large amount of espionage to boot.The Brazilian people themselves, are hard to classify racially. The white portion consists of many European elements, with the Portuguese predominating. In the northern part of the country, the negro population is large, as slavery lasted in Brazil until 1888.

Since color barriers hardly exists, intermarriage is gradually blending the white and black into some intermediate race; the exact outcome at this time being unpredictable. In parts of the country there is still a large aboriginal element, which also tends to go into the melting pot. It is not uncommon, in Recife for instance, to see in one individual traces of all three European, Negro and Indian.

Brazil, since 1930, has been governed by President Getulio Vargas, a native of Rio Grande do Sul., the southernmost state of the twenty Brazilian states. Vargas started his political career as a radical. He became disgusted with the previous political situation, dominated largely by the politicians of the states of Sao Paulo and Minas Gerais. These had created a sort of self-perpetuating regime in which the presidency was tossed back and forth between the two states. Vargas organized the Alliança Liberal (Liberal Alliance) which named him presidential candidate to oppose the old political group in the election of 1930.

When the voting took place Vargas was beaten, due probably to unfair tactics on the part of the “ins” who controlled the polls and were able to count the ballots as they pleased. Claiming with good reason that the election was a fraud, Vargas appealed to arms. A large percentage of the Army went over to him, and a brief campaign in 1930 overthrew the government.

Vargas, on assuming power, began a program of widespread changes, which in their turn aroused opposition in many parts of his turbulent, unwieldy nation. To cope with this he became more arbitrary in his methods, and finally in October 1937, declared the country a dictatorship, which it has been ever since. Brazil at present does not have elections, and there is no time set for Vargas’ term of office to expire. The President rules Brazil through the Army and a system of state governors, called Interventors, who are his personal appointees and whom he may remove at will.

The Brazilian legislative body for the time being is suspended, though it is planned that at some future date it will resume operations. It might be thought that such a regime would lean to the Axis rather than to the democracies in time of war. Such fears were widely expressed in Washington and in the American press. Actually they proved to be exaggerated, as Vargas and Brazilian leaders generally were not copies of Hitler, Mussolini, Franco or any European dictator.

What they were trying to do was to govern a huge, loose-jointed country, suffering from poor transportation facilities and a dearth, in many places at least, of any strong national feeling. This does not mean that Brazilians lack patriotism. In the North, however, poverty and ignorance are so widespread as to make a large percentage of the people indifferent to public and international questions.

Their situation is such that they have to be chiefly concerned with getting the few milreis a day necessary to sustain life.Whether Brazil originally desired it or not, the progress of World War II placed her in an important strategic position. Great Britain, backed by the still neutral United States, was determined to keep German commerce out of the ocean. The Royal Navy attempted to patrol the seas, but had to be spread very thinly over the globe.

The patrol it could maintain was far from perfect, especially after Italy came into the war, and after the ports of Scandinavia and France could be freely used by German shipping. A succession of incidents that occurred in the first part of 1941 is worth mentioning her. On March 3, The German freighter Lech sailed into the harbor of Rio de Janeiro, to be followed six days later by the Hermes, also German.

The Lech remained in port until April 28, when she made for the North , was intercepted by H.M. Ships, and was scuttled. The Hermes stayed on at Rio, where she was joined by a third German freighter, the Frankfurt, on June 4. On the 27th the two ships left together, heading for the North. The Hermes got as far as Lat. 40º N, Long. 35º W , before she was intercepted by British warships and was scuttled.

The fate of the Frankfurt is less certain. It is believed that she too was intercepted and scuttled, but there was some question of identification. As late as June, 1944, the British routing liaison officer at Rio was not prepared to say definitely that the ship was destroyed. At the beginning of the World War II, the United States had two naval contacts with Brazil, both in the city of Rio.

The first was the Officer of Naval Attaché, which is part of the Embassy. This, in ordinary times, is a routine post and performs the duties generally associated with an Attaché’s assignment. The second contact existed through the U. S. naval mission to Brazil, created years ago by contract between the two governments. The mission functions under the Brazilian Minister of Marine, and consists of several United States officers who work in the Ministerio da Marinha, which is housed in a sumptuous building near the water front at Rio.

Its work is chiefly advisory, and in the words of one of its members, Captain Harold Dodd, the Mission might be described as a firm of “consulting engineers”. While it cooperated with the naval Attaché’s Office in pre-war times, no organizational links connected the two.

The existence of these American Naval activities proved extremely valuable for the time came for setting up in Brazil on a much larger scale. However, they were both in Rio; whereas the geographical factors and the actual progress of the war dictated that the North should be most important from a Naval point of view. Hence the Navy first encountered the part of Brazil least prepared to receive it, and all the work there had to be started from bed rock. The case of these freighters is mentioned to illustrate the fact that in 1941 the Royal Navy’s control of the Atlantic was not secure.

The ships reached Rio without detection, and only after this inevitable revelation of their position were the British able to take effective steps. It is no longer a secret that throughout 1941 a de facto state of war prevailed in the Atlantic between Germany and the United States. The Neutrality Patrol conducted by the American Navy in that year gave rise to a number of incidents.

Most of these took place in the North Atlantic but the south Atlantic was affected as well. The beginnings of the South Atlantic campaign can be dated from these pre Pearl Harbor events. During the same months there were taken the preliminary steps that led eventually to the basing of the Fleet on Brazilian ports. At the beginning of the World War II, the United States had two naval contacts with Brazil, both in the city of Rio. The first was the Officer of Naval Attaché, which is part of the Embassy. This, in ordinary times, is a routine post and performs the duties generally associated with an Attaché’s assignment.

The second contact existed through the U. S. naval mission to Brazil, created years ago by contract between the two governments. The mission functions under the Brazilian Minister of Marine, and consists of several United States officers who work in the Ministerio da Marinha, which is housed in a sumptuous building near the water front at Rio. Its work is chiefly advisory, and in the words of one of its members, Captain Harold Dodd, the Mission might be described as a firm of “consulting engineers”.

While it cooperated with the naval Attaché’s Office in pre-war times, no organizational links connected the two. The existence of these American Naval activities proved extremely valuable for the time came for setting up in Brazil on a much larger scale. However, they were both in Rio, whereas the geographical factors and the actual progress of the war dictated that the North should be most important from a Naval point of view. Hence the Navy first encountered the part of Brazil least prepared to receive it, and all the work there had to be started from bed rock.

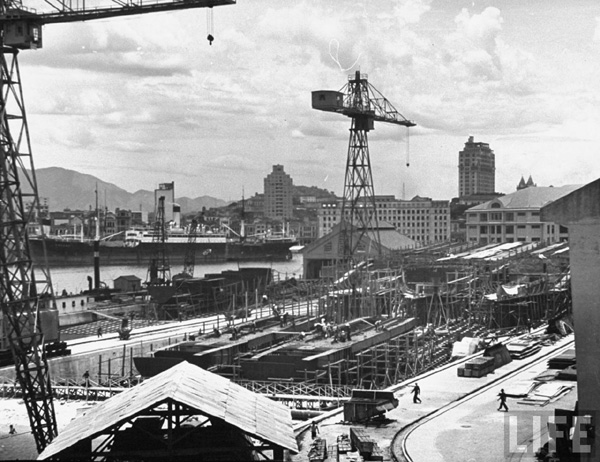

Above, Brazilian Navy Headquarters and Arsenal Rio de Janeiro.

Both pictures shows Brazilian Navy Headquarters Rio. Photo LIFE Magazine.

HyperWar - Commander South Atlantic Force. U.S. Naval Administration in WW II