CAMP INGRAM RECIFE * - CAMP INGRAM *

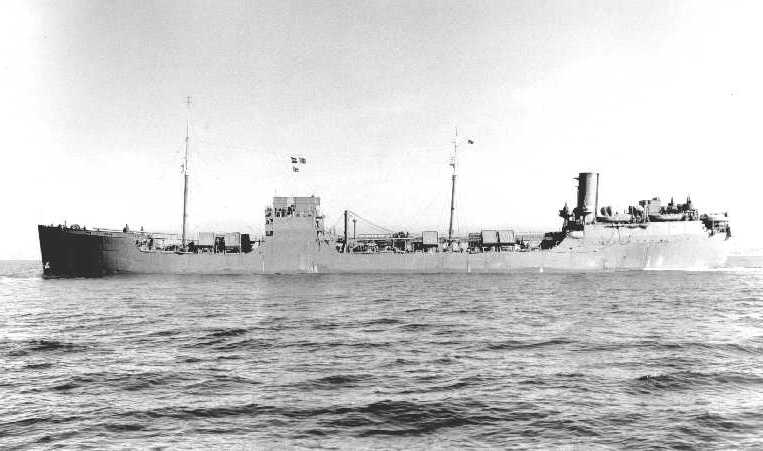

7)SS LIVINGSTON ROE (MAY 43)

Photo U.S NAVY

.jpg)

Above artistic rendition of SS Livingston Roe in flames when moored at Recife harbor.

Built 1921

Tonnage 8,194 / 11,740 tons

Cargo 5.090.000 liters of motor gasoline and 12.762.600 liters of aviation gasoline.

On the morning of 2 May 1943 while Light Cruiser Milwaukee was under repairs at Recife, her crew showed great initiative and skill when fighting a fire on tanker SS Livingston Roe which threatened the harbor. The tanker Livingston Roe, loaded with 5.090.000 liters of motor gasoline and 12.762.600 liters of aviation gasoline, catches fire, near warehouses containing ammunition and dynamite; prompt firefighting efforts by crews of U.S. and British naval vessels in the harbor, from U.S. Navy and U.S. Army shore establishments, and from Brazilian army, aided by naval, and civilian organizations prevented a major catastrophe.

At that time Recife was one of the several foreign ports which the United States Armed Forces used to maintain avenues of communication and supply between the Americas and the European Theatre of Operations. It was the headquarters and center of operations of the United States Fourth Fleet, which was responsible for keeping the South Atlantic area clear of the enemy. It was also the headquarters of the Allies in the South Atlantic and of Admiral Jonas H. Ingram, then Vice-Admiral, who was both Commander of the Fourth Fleet and Commander of the Allies in the South Atlantic.

At that time enemy submarines and blockade runners presented a serious problem. To keep the South Atlantic area clear of the enemy, the Fourth Fleet used a large air force and engaged in extensive convoy operations. Much of the supply and repair work involved in these operations was done in Recife, thus avoiding the necessity of sending ships to Navy yards in the United States for repairs. A Naval Operating Base in Recife, which contained shore-based repair shops, was under Admiral Ingram's command, and supplies for air as well as sea forces were there received and made available.

The Port was under the technical command of Brazilian authorities, but was in fact under the actual control and direction of Admiral Ingram and his staff, by reason of his position as Commander of the Fourth Fleet and Commander of the Allies in the South Atlantic. Libelant was, in May 1943, a Commander in the United States Navy stationed at Recife, a member of Admiral Ingram's staff and directly responsible to him. He was Materiel Officer of the Fourth Fleet and Commander of shore-based repair shops. As he testified, his duties included the maintenance "of the ships of the Fourth Fleet in operating condition at all times." In addition, he was charged with responsibility for the preservation of shore-based facilities which were used in caring for such ships. There was no salvage officer at Recife in May 1943, but Thornton had volunteered for at least nine salvage operations before the one involved here, and these he carried out with noteworthy success.

The Livingston Roe is a tanker which the respondent Standard Oil Company of New Jersey owned on May 2, 1943, but which the claimant Panama Transport Company owned at the time of trial. When the Livingston Roe came south of 10° North Latitude, she was under the protection of Admiral Ingram and he was responsible for her safety. When she arrived at Recife about April 30, 1943, she was under charter to the United States and carried a cargo of 25,450 barrels of motor gasoline consigned to the Standard Oil Company of Brazil, and of 63,813 barrels of high-octane aviation gasoline consigned to the United States Army.

She was berthed alongside Armazem (Warehouse) 2, less than 200 yards from the repair shops which Thornton commanded. Armazem 2 was filled with paints and ammunition, and Armazem 1 adjacent thereto, to the north, contained Army supplies including explosives. The Cruiser U. S. S. Milwaukee was moored to the south alongside Armazem 3. Still further to the south were the Cruiser U. S. S. Memphis, other smaller ships of the United States Navy, and the Brazilian Battleship Sao Paulo. Oil storage tanks were on the inner side of Armazem 1.

On the morning of May 2, 1943, the Livingston Roe was discharging aviation gasoline through a hose overside. Suddenly the hose burst, probably because the valve at the receiving tank ashore was closed before the pump on shipboard was shut off, and the resulting increase of pressure in the hose was more than the fabric could withstand. Before the pump aboard the Livingston Roe could be stopped, the warehouse door, the dock, gasoline drums on the 344 dock, and part of the ship itself were sprayed with gasoline.

The gasoline vapors exploded when a wood-burning donkey locomotive approached the area on a narrow gauge track, which runs along the wharf between the ships and the warehouses. The wharf caught fire, as did the Livingston Roe a few minutes later. The crew abandoned ship, fearing that the warehouse, which was filled with ammunition, would explode. Later, the chief engineer reboarded the Livingston Roe and opened the steam smothering valve, which admitted steam into all the cargo tanks and displaced the air above the surface of the gasoline, thus diminishing the danger of an explosion. He found a party of Navy personnel on board. They released the ship's stern anchor (ships in Recife Harbor put out two anchors because of the prevailing onshore wind). The chief engineer and the Navy personnel left in a Navy boat after the Livingston Roe had caught fire amidships.

At about 10:15 a. m. Thorton was notified of the fire and immediately went to the wharf. There he took various steps designed so save threatened government property, including having the U. S. S. Milwaukee pulled into the middle of the bay by a Brazilian Corvette. He directed firefighting operations from the wharf. A Brazilian Corvette, the Cabedelo, on order of the Brazilian Port Commander fastened onto the Livingston Roe and began to pull her out into the bay.

Thornton, after conferring with a higher ranking officer who had arrived on the scene, of his own volition boarded a Navy boat, which took him out on the bay where he transferred to the tug Fourth October. Thornton prevailed upon the captain of the Fourth October to approach the Livingston Roe in order to fight the fire which was burning fiercely in several places. The Fourth October used its fire nozzle to good advantage in knocking down the heavy flames. The tug then flooded the forward deck of the Livingston Roe to keep the tank tops cool.

At about 12:15 p. m. Navy men in another boat cut the Livingston Roe's other anchor chain on Thornton's orders, and the Cabedelo began to tow her away from the docks. The Brazilian Port Commander aboard the Cabedelo had intended to take the Livingston Roe out to sea and abandon her there to her fate, but Thornton prevailed upon him to beach her at the north breakwater as far from the wharves as possible. Thornton continued to direct the firefighting while the Livingston Roe was being towed. When she was beached on a reef inside the breakwater, Thornton boarded her. Fire parties from Navy ships also boarded. This was about 2:30 p.m.

Once aboard, Thornton continued to direct the firefighting. At about 4:00 p. m. the fire was well under control, and men were sent below to get up steam in the boilers. Thornton left the ship at 2:30 a.m. the next morning, after the fire had been completely extinguished. The Livingston Roe had her steam up, her lights and fire pumps working, had been pulled off the reef, and had her own crew aboard. The airplane gasoline aboard her was safe, and she was available for further tankage services.

It is clear that if the Livingston Roe had exploded, the war effort in the South Atlantic area would have been grievously affected. The Port of Recife could very well have been wiped out. The loss of the Livingston Roe and her cargo of aviation gasoline alone would have been serious in the light of the limited supply of tankers and gasoline which were at that time available and the great demand for both in connection with the air operations of the Fourth Fleet and attached units.

There were five losses being three Americans Wiper George H. De Allaume, Messman William J. Flannery, and Messman Ramon Ruiz, were drowned.Through arrangements made by the Company, they were buried in the British Cemetery at Recife. and two Brazilians and ten injured.

Thornton was promoted to the rank of Captain and awarded the Navy and Marine Corps medal for his fire-fighting activities.

Dramatic view above shows the intense fire spreading throughout the harbor warehouses.

With the fire subsided the signs of destruction were clearly visible.

.png)

The damage was immense, with the loss of tons of material from the Fourth Fleet, including military stores and foodstuffs, canned food, etc.

Rare picture taken from the Warehouse in flames at Recife Harbor following the fire which caught SS Livingston Roe. Photo kindly sent by Brazilian researcher Manoel Felipe

.jpg)

In the detail above, SS Livingston Roe is seen when being towed to an area north of the wharf whilst the fire still is not under control. Photo kindly sent by Brazilian researcher Manoel Felipe.

Above, a large view of Recife harbour where SS Livingston Roe was pumping fuel into the storage tanks nearby. One spark could have ignited the whole facilities.