- THE HARD ROAD TO WAR

9)THE AZORES AND BRAZIL

During the last week of May it looked very much as though the next military step to deal with the Atlantic crisis might be the dispatch of United States ground and air forces to protect either the Azores or northeastern Brazil. After President Roosevelt asked Secretary Hull on 16 May to sound out Portugal's attitude with respect to defense of the Azores, the Department of State first consulted with the British (since Portugal was Britain's ally) to determine their reaction to the President's proposal.

At Ambassador Halifax's request, the Department of State agreed to let Great Britain make the approach to Prime Minister Antonio de Oliveira Salazar of Portugal to discover what his government proposed to do in the event of a German attack and whether he would be receptive to the idea of a temporary protective occupation of the Azores by United States forces.

On 22 May, before answers to these questions were received through the British, President Roosevelt directed the Army and Navy to prepare a joint plan that would permit an American expeditionary force sufficiently strong to insure successful occupation and defense of the Azores under any circumstances to be dispatched within one month's time.

The Army and Navy had been considering for many months past the possibility of being called upon to occupy the Azores. They had drafted the first informal joint plan for such an operation in October 1940. In early 1941 the Army War Plans Division, in reviewing the earlier plan and assessing the current situation, had concluded that an American occupation of the Azores was not essential to hemisphere defense and should not be undertaken unless the United States openly entered the war in concert with Great Britain.

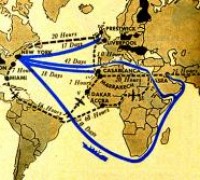

Although the Azores lie athwart the shipping lanes between the United States and the Mediterranean and between Europe and South America, the Army considered them too far north in the Atlantic to be of any value as a defensive outpost against a German approach toward South America via Africa.

The islands had a much greater potential strategic value for Great Britain than for the United States since, if Gibraltar fell, they would provide the British with an alternative naval base from which to cover the shipping lanes in the eastern Atlantic. At the beginning of 1941 the Azores were virtually defenseless, and the Army planners believed that the chief threat to American forces that might be stationed in the islands would be from German airpower based in France.

Air defense of the Azores would be difficult since the islands then had no airfields capable of handling modern combat planes. Under the ABC-1 War Plan, the Azores and the other Atlantic islands (Madeira, the Canaries, and the Cape Verdes) would, in case of open war, fall within the British area of primary responsibility, although American naval forces might be requested to assist the British in the occupation of the Azores and the Cape Verdes.

Until the President issued his directive of 22 May, neither the Army nor the Navy anticipated that Army troops would be called upon to help secure the Azores. The President and the Navy knew that the British had plans for occupying both the Azores and the Cape Verdes as soon as possible after a German move into Spain. While the Army's 1st Division in mid-May was earmarked for an Azores expedition, as well as for many other possible operations, there had seemed little likelihood of employing it for this purpose.

President Roosevelt's order of 22 May led to hasty Army and Navy planning during the next five days to line up the proposed expeditionary force and arrange for it to receive as much preliminary training as possible. One of the principal difficulties was to find enough suitable shipping to transport it. As finally worked out, the plan called for an expeditionary force of 28,000 troops, half Army and half Marine, with strong naval and naval air support. The Army and Marine 1st Divisions were to supply the infantry contingents. To move the force would require a total of forty-one transports and other noncombatant vessels.

The expedition was to be commanded by Admiral King, Commander in Chief, Atlantic fleet, and the landing force by Brig. Gen. Holland M. Smith, commander of the 1st Marine Division. At first, the services planned to send twelve combat landing teams (nine Marine, three Army) to the north shore of Puerto Rico for joint amphibious training. On 26 May this idea had to be abandoned because of the lack of sufficient shipping to carry the troops to and from Puerto Rico.

Instead, limited amphibious training exercises were to be held at Atlantic coast points closer to the Azores--for the Army's 1st Division combat teams, in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts. The shipping shortage was thereby solved, but the ammunition supply was certain to be short of estimated requirements. Nevertheless, by 27 May the general terms of an Azores expeditionary force plan that could be executed in time to meet the President's deadline of 22 June had been agreed upon. The planners thereupon drafted a formal joint plan (code name, GRAY, which the Joint Board approved on 29 May, though an effort also to get the President's approval of it on the same day failed.

Six days before the Army received the President's Azores directive, attention had hurriedly been turned in another direction-toward Brazil. The Army and Navy had agreed since the initial RAINBOW planning of 1939 that the most vital region to be defended in South America was the Natal area of Brazil. By May 1941 the military airfield program being sponsored by the United States Army was well under way in the Caribbean area and along the northeastern coast of Brazil.

The air base sites and partially developed fields in Brazil were virtually unprotected, and if left undefended might offer a Nazi air invasion from Africa a ready-made approach route to the Caribbean, instead of serving their intended purpose of providing an American air defense route to the Brazilian bulge. During the fall and winter of 1940-41 the Army had discussed with Brazilian military authorities the possibility of placing American air base security detachments at the various airfield sites, but it had not been able to persuade the Brazilians to agree.

Brazil's first open military collaboration with the United States was with the Navy. The Navy's Western Hemisphere Defense Plan No. 2 had provided for cooperative action with Brazilian naval forces in the patrol of the South Atlantic. Although Brazil did not immediately participate in the patrol, it did agree in April to open two Brazilian ports to American naval vessels, and thereby it established a precedent for the entry of Army forces into Brazil.

A month later, the prospect of an imminent German drive southwestward had led to Colonel Ridgway's urgent mission to Rio de Janeiro. While Colonel Ridgway was talking with Brazilian authorities, the War Plans Division was formulating the Army's view as to "the most practicable. immediate course of action to prevent the entrance of Axis military power in the Western Hemisphere.” The Army planners currently viewed the war situation and the probable course of German action in these terms:

I- The Situation. Germany is now engaged in a struggle for control of the Mediterranean, the Suez Canal, the oil fields of Iraq and Iran, and North Africa. Prospects for German success are good. By her air force, Germany now holds the initiative in the Western and Central Mediterranean. There are repeated reports of German infiltration toward Dakar. The Vichy Government has finally submitted to German domination. French West Africa is open to use by Germany for bases for extension of Nazi power to South America.

II - Assumption. That immediate and vigorous preparations are being made to extend Axis political, economic, and military power to South America.

III - Axis Courses of Action. The first and most logical Axis step to project Axis power into South America would be to establish a base on the West Coast of Africa. The obvious advantages of a base in the Dakar area, coupled with the fact that Dakar is in French hands and Axis domination of France is increasing, make it apparent, without further exposition, that Dakar would be the prospective Axis base site.

The most effective response to this German threat would be to dispatch a large expeditionary force to Dakar, or to British West Africa further to the south. But the Army had already calculated that such a force would have to number between 100,000 and 115,000 troops-far beyond existing Army means-in order to assure success. A force of this strength could not be sent to Africa before November 1941 at the earliest.

Yet the planners believed that the United States ought to do something-as their study put it, "there is almost universal opinion that BLUE [the United States] should adopt some course of action in the immediate future to forestall Axis intentions toward South America." The United States had the means to develop naval and air bases in Brazil, and that was the immediately practicable course of action that War Plans recommended to General Marshall on 27 May.

In considering the Azores and Brazil projects, Army planners had to bear in mind the qualified commitment already made in ABC-1 to send Army forces to the British Isles and Iceland sometime after 1 September 1941. Current and prospective shortages of air and antiaircraft artillery forces, and of ammunition, made it appear unlikely that the Army could carry out effectively more than one of these projects before early 1942. As between the Azores and Brazil proposals, only the latter would be of direct advantage in hemisphere defense.

The Azores operation would detract much more than the Brazilian from American ability to carry out the ABC-1 commitment. On the basis of these observations and assumptions, a War Plans study of 27 May contended that the United States would have to choose between "two mutually exclusive courses of action which can be undertaken effectively with the Army forces available during the coming summer and fall." These were: I - To protect our interests and the Western Hemisphere by assisting the British to maintain their position and ultimately defeat Germany.

II - To postpone Army aid to the British in order to insure the immediate security of the Western Hemisphere against possible Nazi attack or political control [through subversion] in Brazil. This study concluded by recommending the second course of action, to be implemented on the one hand by the immediate dispatch of a balanced United States Army force to the Natal area and on the other by making every effort to prepare the forces required to carry out the ABC-1 commitment at some date later than 1 September 1941.

If this recommendation were disapproved, then the British should be consulted as to their preference between an Azores expedition and carrying out the ABC-1 commitment during 1941, since the United States Army could not do both. If the decision were for the Azores, the expedition should be postponed at least until 15 August 1941 in order to assure its success through adequate training and preparation.

Transcribed by Patrick Clancey. HyperWar Foundation